|

| |

Vasyugan River and Vasyugan Khanty Culture

(A.Filchenko)

|

|

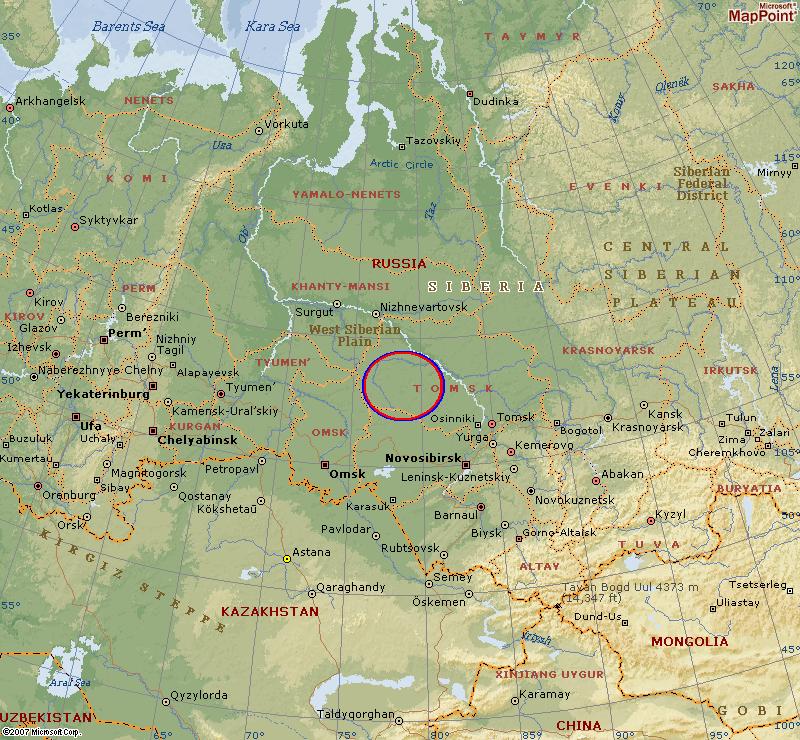

Vasyugan is the western tributary of the

Ob river in the middle of the Western Siberian Plain east of the Ural

mountain range, in the Kargasok district of Tomsk

region.

The low-lying local landscape consists of a multitude of rivers and

lakes, which drain the world’s largest bog lands – the Vasyuganskie

Bolota (Vasyugan swamp).

The general

climate and ecosystem

of the Vasyugan basin is typical for

western Siberia, characterised by an

extreme continental climate, with temperatures

ranging from +30C' in

the short summer (May-August) to

-40C'

in the long winter

(October-March).

Local fauna include bear, elk (moose),

deer, wolves

and a range of other fur-bearers and wildfowl. Traditionally, much of the

Vasyugan Khanty diet consisted of fish.

Such species as

pike,

bream, perch, starlet among

other species are

a frequent catch

locally.

In contrast to other Khanty groups, the

Vasyugan Khanty had no local

tradition of reindeer husbandry

due to

the specifics of

local ecology, dense mixed forests lacking

reindeer pasture, numerous streams,

rivers, lakes and

vast

bogs.

Traditionally the Vasyugan Khanty were subsistence hunters and fishermen.

Their

low scale seasonal

migration were motivated primarily by the

main occupations,

hunting and fishing,

and

consisted

of repeated trips from the permanent riverside village out to the

clan

hunting territories in October-December

and January-March,

followed by downstream migrations to family-owned fishing locations. The

hunting grounds are traditionally equipped with one or more small hunting

cabins with storage huts elevated above the ground on poles; whilst at

summer fishing locations families would build makeshift tents and shelters

using birch bark and poles.

The routines of seasonal

mobility were also reflected in the traditional

calendaric terms.

These names do not

equate directly to European notions of months, and may vary in length, both

from one period to the next, but also from one year to the next depending of

climatic, ecological or other practical factors. As a result, these

concepts map sequences

of

behaviours,

rather than purely temporal notions.

Each season had a common lexical component of

iki 'loose equivalent of

‘moon’':

kör«k-iki

‘time of eagles’ (~March);

urn-iki

‘time of crows’ (~April);

lontwäs«k-iki

‘time of geese and ducks’ (~May);

pojalt«w-iki

‘time of the snow crust’ (~December),

etc

(Filtchenko, 2000-2005; Tereskin, 1961; Gulya, 1965; Sirelius, 2001; Lukina

2005; ).

The prevailing majority of the traditional Vasyugan Khanty permanent

settlements (yurt

(local topology term of Turkic etymology),

puɣol (native Khanty term) are located along

the Vasyugan River, in widely-spaced

pattern, often several

hours and

days by boat from one another.

Exceptions to this

pattern include occasional settlements on the shores of the region’s major

lakes. This settlement

pattern

of extended family villages

reflected the structure of traditional social organization which was based

on patrilocal, patrilineal exogamous lineages.

The native reference term used

for this social grouping is

aj puɣol jaɣ

'same village

people'. The word

puɣol "village" normally refers the

typical Khanty settlement of 2-3

huts at the river or

lake edge, and housing a small community of 10-15 people.

Besides

more localised clan and lineage identities,

historical accounts (Haruzin, 1905; Sokolova, 1983) suggest that the

Vasyugan Khanty

were

aware of

larger social,

localised

‘ethnic’ groupings, mainly on the grounds of linguistic affinity.

These

groupings

referred to

the major rivers the group occupied,

äs’ jaɣ

'Ob-river

people',

waɣa jaɣ

Vakh-river

people',

wat’

joɣ«n

jaɣ

'Vasyugan-river

people,

and at

a larger

level yet,

eastern

Khanty

groups describe themselves as

qant«ɣ

jaɣ

'Khanty people'

- a

compound

term

combining

the ethnonym for

eastern Khanty

qant«ɣ

‘Khanty’

(distinct phonetically from the western Khanty self reference term

xanti

'Khanty')

and the term

jaɣ

with the general sense 'people' (Tereskin, 1961).

More

detailed descriptions

of Vasyugan kinship and social organisation

can

be

found

in (Kulemzin

and Lukina 1976; Filchenko -

forthcoming).

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The

Khanty of

Vasyugan are confident that their ancestors have long resided

on these territories and refer to them as

äreŋ jaɣ

meaning 'ancient people',

who,

according to folklore,

were

in frequent conflict with Tatars

(qatan’

jaɣ),

which is evident, in folk interpretations,

from

archaeological sites in the landscape,

including

the remains of fortified settlements, scatters of metal arrow heads

and

occasional swords and pieces of body armour. The

ancestors,

occupants of these sites

were

the

warrior-hero progenitors of the

Vasyugan clans, who lived in the region and defended it from attacks and

occupations by Tatars from the South and Nenets (jor«n

jaɣ)

from the North (Lukina, 1976).

The rich spiritual life of these communities was the object of

description by

late XVIII -

early XX

century travelers and

ethnographers

(Sirelius 2001;

Karjalainen 1921, 1922). The

language of Vasyugan Khanty was much lesser described in occasional

sketches and word lists (Karjalainen 1913).

The

life of all Khanty and animals was created and predestined by

tor«m,

a chief deity. Another ultimately powerful deity is the female

mother-spirit

puɣos äŋki,

the giver of life and soul (il),

and judge of its length and quality (Karjalainen, 1927).

There

is also

numerous

powerful masters of elements: the water/river deity

äs’ iki,

the master of fish and a multitude of water spirits and demons; the

forest deity

wont iki,

the master of animals and birds and of

the

forest spirits.

The Vasyugan Khanty also

used to keep

images of so-called home or family spirits (juŋk)

which were linked to the welfare

of individuals and families,

success of hunting

and fishing.

Dated accounts describe

the

events when the

spirits

were

sat at a table and offered food, typically by a man, before hunting and

fishing seasons, to give luck and rich spoils.

Various locations along the

Vasyugan

river were known as homes of a variety of local spirits, mostly of anthropomorphic nature, in

the

shape of a woman or a man, and

in having wooden

figures representing

their image. The sacred sites, “homes” of the spirits continue to be

distinct and known to local families and regularly attended for

offerings and paying respects. For

Vasyugan

Khanty, it was also typical to have anthroponymic group-names (Vertesh

1961, Lukina 1978) typically corresponding

to the names of the clan progenitors:

kotʃ«t

'badger',

kötʃ«rki

'chipmunk',

köraɣ

'sack' (Filtchenko, 1998-2005).

The sacred rituals were

typically performed by the hunters themselves,

however, often the

shamans

(jolta

qu)

were invited to make offerings to the spirits and ask for rich spoils in

hunting/fishing, but

more

typically

to act

in the role of medicine men and fortune-tellers (Dmitriev-Sadovnikov,

1911; Karjalainen, 1922; Zuev, 1947; Kulemzin, 1976).

The unique role of

shamans was their ability in the process of shaman rituals to part with

their body and ‘walk the worlds’ (lower or upper) and to communicate and

interact with spirits and deities, act on other people’s souls/spirits,

and foresee the future

and help build the

strategies for successful hunting, as well as to

foresee

the individual

hunters'

fate.

In case of illness

treatment, the shaman’s spirit was typically expected to travel to the

lower world to find and return the stolen spirit of the ill person.

Alternatively, the shaman was understood to heal the person by expelling

the spirit of illness from the body of the ill, fighting it in the

spiritual realm, often in alliance with either the family/clan spirit or

the local patron spirit

(Kulemzin, 1984).

Shaman’s

skills were combined

the intimate experience with the whole pantheon of spirits and deities,

as well as general close

knowledge of the

local landscape, flora and both behaviour of and towards animals.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The first Russian contacts with

Vasyugan Khanty date back to XVI century at which time

they

had resided at this location for at least 3 to 10 centuries based on

archeological research. Before the Russian contact,

Vasyugan Khanty are

assumed to have been in contact with Siberian Tatars, as the area was

under administrative control of Siberian Tatar Khan. Based on available

folk data, language/culture contact with Tatars and among other local

ethnic groups was fairly limited, with inter-ethnic relations generally

described as hostile.

Early Russian colonial policies were

conservationist with minimal Russian language contact and assimilative

pressures, with the exposure to Russian growing considerably in the end

of the XIX century and increasing radically in 1930-1960s as a result of

the soviet collectivization and forced migration (exile) policies. Since

1960s-1980s most of the area was heavily assimilated due to policies of

social engineering, mandatory secondary schooling (Russian media

boarding schools) and particularly by the mineral resource exploration

programs resulting in considerable influx of non-native population from

European Russia, Ukraine and central-Asian regions.

For

the Vasyugan Khanty language

the situation of neglect and discrimination has been a reality. Speakers

are ridiculed by the mainstream majority, children are not taught, and

in some cases persecuted for speaking

Khanty at schools. The common ethnonym ostyak is perceived as pejorative, while the stereotypes

about Khanty in general public remain uninformed. All

Khanty speakers

are bilingual with Russian being the language of daily communication

across ethnic groups. Khanty undergoes a steady decrease of the

functional sphere, reserved primarily for occasional family use, rare

peer communications and extremely rare traditional religion (shamanism)

contexts.

The majority of

Vasyugan Khanty are

currently linguistically assimilated Russian monolinguals numbering

under 150 pers. The numbers of Vasyugan Khanty officially registered

vary from source to source, however, based on the original research

there are around 20 Khanty who permanently reside on

Vasyugan river and

have practical knowledge of traditional language and culture. They are

bilingual minority native language speakers, all over the age of 50.

The number of semi-fluent speakers,

capable of maintaining restricted basic conversations in

Khanty does not

exceed 50, principally placing these dialects in the group of languages

in the imminent danger of extinction within a single generation.

|

| |

|

|

References:

Chernetsov, V.N. K istorii rodovogo

stroja u obskix ugrov. SE, VI, VII.

Dmitriev-Sadovnikov,

S reki Vakha, Surgutskogo uezda. ETGM, V-19. Tobolsk. 1911.

Filtchenko, A.Y. Field notes from ethno-linguistic

research of Eastern Khanty. The Field Archive of the Laboratory of

Siberian Indigenous Languages at TSPU. Tomsk.

Haruzin, N. Ethnography. V-IV.

Verovania.

1905.

Jordan, P. & Filtchenko A.

Continuity and Change in

Eastern Khanty Language and Worldview. In: “Rebuilding Identities:

Pathways to Reform in Post-Soviet Siberia" edit. Erich Kasten. Dietrich

Reimer Verlag 2005.

Karjalainen, K.F. Die Religion der

Jugra-Völker. Parvoo. 1927.

Kastren, M.A. Puteshestvie po Laplandii, Severnoj Rossii i Sibiri.

Moscow. 1860.

Kulemzin

V.M. Semja kak faktor socialnoj stabilnosti v tradicionnom obshestve,

in: Voprosi Geografii Sibiri 20: 1993.

Kulemzin

V.M. Celovek i priroda v verovanijakh Khantov. Tomsk. 1984.

Kulemzin V.M., Lukina N.V. Novije dannije po socialnoj

organizacii vostochnih hantov, in: Iz istorii Sibiri, vip. 21, Tomsk.

1976.

Kulemzin

V.M., Lukina N.V. Vasjugansko-vahovskije hanti, Tomsk. 1976.

Kulemzin

V.M., Lukina N.V. Znakomtes’: Khanti. Novosibirsk. 1992.

Kulemzin

V.M. Mirovozzrencheskie aspekty ohoty i rybolovstva. In. V.I.Molodin,

N.V.Lukina, V.M.Kulemzin, E.P.Martinova, E.Schmidt, N.N.Fedorova (eds.)

Istoria i kultura Khantov. Tomsk. 1995. pp.45-64.

Lukina,

N.V. Nekotorie voprosy etniceskoj istorii vostocnyx xantov po dannym

folklora.//Yazyki i Toponimiya. Tomsk. 1976.

Lukina

N.V. Voprosi etnografii vostocnix xantov v svete novix dannix.//Acta

Ethnographica Hungarica, 43 (3-4): 1998. Budapest.

Lukina,

N.V. Obshee i osobennoe v kulte medvedja u obskix ugrov. // Obrjady

narodov severo-zapadnoj Sibiri. Tomsk. 1990.

Lukina,

N.V. Istroia izuchenia verovanij I obrjadov. In. V.I.Molodin, N.V.Lukina,

V.M.Kulemzin, E.P.Martinova, E.Schmidt, N.N.Fedorova (eds.) Istoria i

kultura Khantov. Tomsk. 1995. pp.45-64.

Lukina

N.V. Khanti ot Vasyuganya do Zapolyarya. T-I. TGU. Tomsk. 2004.

Lukina

N.V. Khanti ot Vasyuganya do Zapolyarya. T-II.

TGU. Tomsk. 2006.

Sarkany Mihaly. Female and Male in Myth and Reality, in:

Uralic Mythology and Folklore, Bp., Helsinki. 1989.

Sirelius,

U.T. Puteshestvie k Khantam. Tomsk. TGU. 2001

Sokolova,Z.P.

Sotsialnaja organizatsija hantov i mansi v XVIII-XIXvv. Moskva Nauka.

1983.

Startsev,

G. Ostyaki. Moscow. 1928.

Steinitz, W. Dialektologisches und etymologisches

Woerterbuch der ostjakischen Sprache, Lief.1,2-3, Berlin.

1966.

Tschernetsov W.N. Bärenfest bei den Ob-Ugriern. – Acta

Ethnographica Academiae Sceintiarum Hungaricae, t.23 (3-4).

Budapest, 1974.

Tyler, S. Cognitive Anthropology.

Waveland. 1969.

Vertes, E. Beitrage zur Methodik der

ostjakischen Personennamenforschung.//VI Internationaler Kongress fur

Namenforschung. Bd.III. Munchen. 1961.

Zuev, V.F. Opisanie zhivushchix v

Sibirskoj gubernii v Berezovskom uezde inoverceskix narodov ostyakov i

samoedov. Moscow. 1947. |

|