|

| :: FINAL RESEARCH PAPER |

|

ACCOMMODATING THE URBAN INFORMAL SECTOR IN THE PUBLIC POLICY PROCESS: A CASE STUDY OF STREET ENTERPRISES IN BANDUNG METROPOLITAN REGION (BMR), INDONESIA |

|

The informal economy, in all the ambiguity of its connotations, has come to constitute a major structural feature of society, both in industrialized and less developed countries. And yet, the ideological controversy and political debate surrounding its development have obscured comprehension of its character, challenging the capacity of social sciences to provide a reliable analysis. Portes, Castells, and Benton (1989:1) |

|

By Edi Suharto

2003 International Policy Fellow |

|

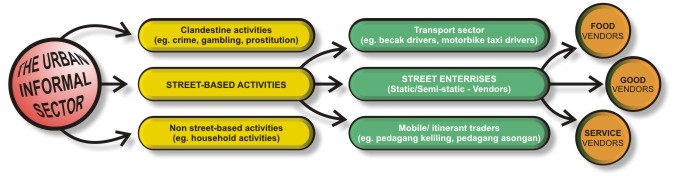

Abstract The role of the urban informal sector (UIS) in development has been one of the many contentious issues in the public policy area. In Indonesia, evaluation and policy attention toward the UIS is mainly concerned with the high growth rate of the sector and with its negative effects on the urban built environment. This is especially true for street enterprises, the most dominant sub-group of the UIS in the country. Their continued presence in the markets and sidewalks of the cities produces a variety of conflicting opinions about the importance of their retailing activities in the overall urban economy of Indonesia. The objectives of the project are to analyze social and economic factors underlying street vending activities; discuss relevant policy issues and develop policy options in the urban development planning of BMR; and write a research and policy paper for city administrators, urban planners, member of parliament, academia, NGO workers, mass media reporters, and street traders (including street trader associations) in BMR. As a result, the project will come up with two interrelated papers, namely research paper and policy paper.The main aim of research paper is to provide basic information of the socio-economic characteristics of street enterprises in BMR, as well as major features of existing policy measures and legislations relating to the operation of street enterprises in the study area. The policy paper is intended to use the findings of the research paper to enhance the sound process of public policy making and suggest open and integrated policy measures to public policy administrators concerning the operation of street enterprises within the adequate framework of urban built environment. INTRODUCTION The informal sector is known by many different names according to different contexts and points of view. Variously referred to as the informal economy, unregulated economy, unorganised sector, or unobserved employment, to cite but a few of its titles, this sector typically refers to both economic units and workers involved in a variety of commercial activities and occupations that operate beyond the realm of formal employment (Williams and Windebank, 1998; Suharto 2002). In the urban context, the informal sector refers to small enterprise operators selling food and goods or offering services and thereby involving the cash economy and market transactions. This so-called “urban informal sector” (UIS) is more diverse than the rural one and includes a vast and heterogeneous variety of economic activities through which most urban families earn their livelihoods. Activities of the UIS in the public arena of cities are particularly apparent in street-based trading, which is widely known as street vendors or pedagang kakilima in local language. Although these street enterprises are mostly hidden from the state for tax, they involve very visible structures, and are often subject to certain limited administrative processes, such as simple registrations or daily collection fees. The main forms are retail trade, small-scale manufacturing, construction, transportation, and service. These economic activities involve simple organisational, technological and production structures. They also rely heavily on family labour and a few hired workers who have low levels of economic and human capital and work on the basis of unstandardized employment laws (Suharto, 2000; 2001; 2002). With reference to street enterprises, the issue of the informal sector is particularly related to its business operation. The street traders operate their businesses in the areas that can be classified as public spaces and are originally not intended for trading purposes. As most street trading occupies busy streets, sidewalks, or other public spaces, it is often considered illegal. This status makes these traders victims of harassment and threats from police and other government authorities. In Bandung City, for example, the municipality government continues to perform clearance operations in the seven busiest areas (expanded from five areas since 2001), namely Jalan Sudirman, Asia Afrika, Dalem Kaum, Kepatihan, Dewi Sartika, Otista, and Plaza Bandung Indah complex. The government believed that these areas should be free from the “nuisance” of pedagang kakilima, especially during event days. This actually often involves a policy of “clear-the-streets and arrest-vendors” that removes the street enterprises from the areas in which they have been operating. THE PROBLEM According to Yankson (2000:315), as the urban informal economy expands, there is bound to be a proliferation of workshops and worksites or an intensification in the use of informal economic locations. This would breed and exacerbate environmental problems, such as traffic and health hazards, which are associated with the operation of informal economic activities. Therefore, there is an increased demand for suitable sites for such enterprises with requisite infrastructure and services. Unless the urban development planning responds with the appropriate policy and programmes, the prospects for their growth and development cannot be initiated. A failure of the urban management system to integrate them in the city master plan will result in a haphazard and scattered locational pattern of informal economic enterprises within the urban built environment. In BMR, there are areas of visible agglomeration of such enterprises, particularly along the major transport arteries and streets (e.g. the streets of Asia Africa, Dalem Kaum, Kepatihan, and Dewi Sartika) and in road reservations in the city. They are also concentrated in other areas, such as public markets, commercial complexes, and bus stations, where crowds congregate at the day and night. Above all, they are found in public spaces and low-income residential neighbourhoods, usually through squatting on public or privately owned land. In BMR, very little, if any, attention has been paid to integrating the UIS in urban development planning. While the municipal and district government have no adequate understanding on the nature of micro-economic activities, the local government authority has not seriously considered the aspirations and needs of street traders. This project will therefore address these issues, and integrate them within the urban space and economy. This will enable policy makers and city administrators to identify a number of policy options and programmes in accommodating the operation of small and micro-enterprises. In addition, the results can also be shared for policy analysis in some advanced countries, especially in the European Union nations which are now witnessing the exclusion of an increasing production of the citizens from both formal employment and welfare provision and hence experiencing the growth of the informal economy (Williams and Windebank, 1998:29). LITERATURE REVIEW In most countries, both developing and developed ones, activities in the informal sector were not included in national employment statistics (Suharto, 2002). In an attempt to bring this sector to national attention as well as to reduce the concern over high unemployment, the inclusion of the sector in national figures has now become a common feature in many developing and developed nations alike (see Portes, Castells and Benton, 1989; Thomas, 1992; Williams and Windebank, 1998). However, their activities, which are mostly unregistered and unrecorded in national income accounts, are still the main determinant in referring to the sector as informal. The main reason is that the activities are almost always outside the scope of state regulation and protection. Even if their activities are registered, the informal sector does not follow any labour protection, job security and other protective measures of the workplace (see ILO, 1998; UNDP, 1997; Williams and Windebank, 1998). Defining the UIS and Street Traders In the urban context, the informal sector is often referred to as consisting of small enterprise operators selling food and goods or offering services and thereby involving the cash economy and market transactions. This informal enterprise is more diverse than the rural one and includes a vast and heterogeneous variety of economic activities through which most urban families earn their livelihoods. The main forms are retail trade, small-scale manufacturing, construction, transportation, service, and domestic work operating either as home-based or public-based activities. Activities of the UIS in the public arena of cities are particularly apparent in street-based trading. Although these street enterprises are mostly hidden from the state for tax, they involve very visible structures, and are often subject to certain limited administrative processes, such as simple registrations or daily collection fees. Putting the distinction of street traders under the umbrella concept of urban informal sector, Suharto’s study in Bandung (2002) generates a typology of those categorised as street traders or pedagang kakilima compared to other urban informal activities as shown in Figure 1. On the basis of observations and interviews on their appearance suggest that the pedagang kakilima in Bandung meet all or most of the following criteria: |

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 1: A typology of pedagang kakilima

Source: Suharto (2002:189) |

Note that this study avoids the terms “shadow”, “invisible”, or “hidden economy”. This means that it does not assume the informal sector as an economic activity in the hidden interstices of contemporary society. It is argued that the informal sector is observable in the communities in which it takes place and even in areas where informal activity is condoned, it remains visible not only to society, but also to the state authorities (Williams and Windebank, 1998). This study also avoids the other common tendency of referring to the informal sector as a criminal activity, known as the “black”, “underground”, or “clandestine economy”. It is held that unless the informal activity is illegal by nature, it is considered legitimate and legal in all other respects. The term informal sector is therefore not synonymous with criminal, antisocial, or morally questionable activities, such as theft, prostitution, drug dealing, or gambling. Role of the UIS The role of the UIS in development has been one of the many contentious issues in the public policy area. In Indonesia, evaluation and policy attention toward the UIS is mainly concerned with the high growth rate of the sector and with its negative effects on the urban built environment. This is especially true for street vendors, the most dominant sub-group of the UIS in the country (Suharto, 2002). Their continued presence in the markets and sidewalks of the cities produces a variety of conflicting opinions about the importance of their retailing activities in the overall urban economy of Indonesia. The importance of the informal sector to Indonesia’s development is obvious. High and uneven population distribution, an increasing rate of growth of urban population, and the effects of slow industrialisation call out for initiatives to create employment alternatives for an unprecedented growth of the labour force. During the 1990s, the employment situation in Indonesia was particularly difficult as employment opportunities in the formal sector were unable to absorb the growing labour force within the national labour market. Between 1990 and 1997, while the labour participation rate increased from 55 percent to 58 percent, the work opportunity rate decreased from 97 percent to 95 percent. As a result, the open unemployment rate increased from 1.7 percent to 4.7 percent during the same period (CBS, 1995:19; CBS, 1997:1). Indonesia has one of the largest informal economies in the world. As in many other Third World countries, the informal sector in Indonesia still accounts for most of the total employment and has, therefore, a larger impact on creating a more equitable distribution of incomes in rural as well as in urban development. During the 1980s and 1990s, the number of those who constitute the economically active population and who depend on the informal sector as their main source of employment and income has been consistently more than sixty percent of the total labour force (see Suharto, 2002). In 1998, it consisted of 43 million in rural areas and 14 million in urban areas or about 65 percent of the total working population (CBS, 2001; Hugo, 2000:125). In 2000, out of 89,837,730 working population, the number of informal sector was 58,307,164 people (64.90%) As widely reported by national and local newspapers, the growth of the informal sector was particularly high during the recent economic crisis. The crash of the modern economy between 1997 and 1999, involving the closure of banks, factories and service agencies, pushed the newly unemployed to more than double in the informal sector. In the case of street enterprises, the increase is even more impressive. In Jakarta and Bandung, for example, from the end of 1996 to 1999 the growth of the street vendors was estimated at 300 percent (Kompas, 23 November 1998; Pikiran Rakyat, 11 October 1999). Despite the fact that the informal sector provides a livelihood for huge numbers in the national labour force, this sector continues to have low productivity, poor working conditions, low incomes and few opportunities for advancement. Although some of the more structured groups of the informal sector, such as street traders, tend to have an entrepreneurial character and sometimes high incomes, it is widely recognised that the informal sector is still vulnerable, with little capital, limited markets, inadequate economic returns, and low levels of living standards (Suharto, 2001). Business and Locational Decisions of the UIS In cities of developing countries, informal economic activities are found in almost all main roads and arteries as well as in residential areas. Therefore, it is important to understand why the operators of these small-scale informal enterprises choose the sites or locations where they run their enterprises. To arrive at this understanding, the analysis of some theoretical models of industrial locations is required. Amin (1993), amongst others, has suggested agenda for the integration of the UIS in the urban planning process. He believed that such accommodation could lead to better management of the urban economy and the environment than otherwise. However, the integration of the UIS into the urban planning needs to address a number of issues. At least, the issues involve questions regarding how to provide the sector with access to appropriate worksites, adequate and suitable workshops, environmental services and security of tenure for sites of the vendors (Yankson, 2000). Perera (1994) has argued that the lack of suitable premises for production and marketing is a fundamental limitation of the growth of informal enterprises, because such a deficiency inhibits capital investment and the creditworthiness of these enterprises. Hence access to permanent workplaces at suitable locations is essential for capital investment, increased production and productivity for informal enterprises. According to Sethuraman and Ahmed (1992) this approach could facilitate technological upgrading aimed at improving the quality of the goods and services produced within the informal economy. Yankson (2000:316) suggested that the location and site selection of the operators of informal economic units is at the core of the integration issue. He maintained that the locational pattern of the units has influenced the operators’ decisions to select land use configuration and to invest in them. The locational pattern also has a bearing on employment and environment relationships. In views of a number of authors, such as Wbwer (1929), Isard (1954), Lösch (1954) Alonso (1975), Glasson, 1978, and Hoover, (1984), Yankson further outlined the main tenet of location theories. He stated that there are two main lines in the locational theories: the classical location models, which seek to maximise profits through the last cost approach, or via the maximisation of sales. However, Yankson (2000:316) confirmed that: Location is not simply a matter of achieving maximum profits, whether through minimisation of costs or maximisation of sales. There are other variables that need to be considered: locational interdependence, the difficulty of evaluating the relevant variables, especially costs in different locations, market conditions and the policies of rival firms, and whether firms indeed seek to maximise their profits or not. According to Yankson (2000), the classical model is not a good framework for studying the location decisions of small firms, particulalrly in developing countries. The model does not allow for uncertainty, hence it probably cannot satisfactorily explain the spatial behaviour of small entrepreneurs in non-Western countries. He then argued that the behavioral model developed by Pred in 1967 is likely to be more beneficial and complementary to the classical model (Yankson, 2000:317). It focuses on people’s incomplete knowledge and inability to utilise the available information in order to obtain optimal location in terms of concerned profits. These considerations are then used by Dijk in 1983 to develop a framework, called behaviouristic location model, to analyse small enterpirses in which the model places uncertainty as a main point (Yankson, 2000). As Yankson (2000:317) asserts: This uncertainly arises from the illegal status of most small enterprises, the lack of tenure or security of their plots, their inability to secure suitable sites and legal title to land, the illegal status of their workshops and a land use planning system that does not take their interests into consideration. To analyse business and locational decisions of

the UIS, this study draws on the issue of site selection guided by Dijk’s model

and developed further by Yankson framework. The model outlines a scenario of

location and identifies the factors that are likely to influence the relocation

of an enterprise. It includes: security of tenure, the personal relations

between an entrepreneur and his or her customers, and the price of a plot or

workshop.

Highlighted by a study on hawkers in some Southeast Asian Cities, McGee and Yeung (1977:42-44) have made an analytical model of policy stances towards the hawkers by setting three spheres of activities with regard to location, structure and education as presented in Table 1. The activities fall into a continuum of actions range from positive to negative going from left to right in the table. |

Table 1: A Model of Policy Approaches

towards Hawkers

|

|

The first is locational actions designated to interfere with the ecological patterns of hawkers. These may be undertaken by conducting clearance operations (negative attitudes) or offering new legalised sites (positive attitudes). The second is structural actions designed to eliminate or develop the hawkers according to their economic base. For example, actions intended to eliminate the hawkers would be government takeover of marketing chains or government encouragement to the growth of alternative employment opportunities at higher incomes to make hawkers leave their job. Actions geared to develop the hawkers could well take the form of provision of monetary credit facilities for expansion of hawker operations. The third is educational actions designated to change the attitudes towards hawkers or among hawkers. The negative policy would be the public campaign stressing the danger of purchasing commodities from hawkers from the hygiene point of view. Whilst the positive one could be the provision of training for hawkers in such areas as hygiene and sanitation practices, business management, marketing, bookkeeping, and customer relation. OBJECTIVES OF THE PROJECT The project basically aims to produce two interrelated papers, namely research paper and policy paper, with regard to the operation of street enterprises within the context of urban development planning of BMR. The research paper is intended to (a) identify major characteristics of street vending and working and environmental conditions of the enterprise in which they are operating, such as business profiles, social and economic determinants of street vending activities, and factors influencing the selection of worksites of the street traders in the urban space economy; and (b) highlight existing policy measures and legislations relating to the operation of street enterprises, such as approaches of the measures, problems and implementation patterns, stakeholders (advocates, opponents, decision-makers) involved, and participation and communication procedures in policy-making. The policy paper is intended to (a) increase the awareness and involvement of different policy stakeholders so as to enhance the sound process of public policy making; and (b) suggest open and integrated policy measures and interventions to public policy administrators concerning the operation of street enterprises within the adequate framework of urban built environment. RESEARCH STRATEGIES Research Methods The type of research undertaken by this study was the triangulation method. This mixed-research strategy involves different quantitative and qualitative research approaches and multiple techniques of data collection, such as surveyed questionnaires, observations, focused interviews, and document study. The fieldwork for this study was located in Bandung Metropolitan Region (BMR) for about three months, between June and August 2003. The triangulation method refers to a combination of strategies to study the same phenomenon employing “between methods” or “across methods” derived from multiple quantitative and qualitative techniques of data collection (Suharto, 2002). As identified by Greene, Caracelli and Graham (1989), the purpose of the triangulation method is particularly to seek convergence, corroboration, and correspondence of results from the different research strategies (Suharto, 2002). This method leads to more confidence in the results and generates an innovative approach to the study of social issues. Selection of Research Sites and Respondents Bandung Metropolitan Region (BMR), the city selected as the study area, shares much in common with other large Indonesian cities in terms of the level and pace of urban development as well as the severe economic downturn associated with the recent structural adjustment period. Bandung is the capital of West Java province situated 180 kilometres southeast of Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia. With population of over 4 million, BMR is one of the Indonesian cities that serves as a regional centre for administrative and business activities. This makes it a destination for rural migrants in search of employment as it has large and varied informal activities, including household-based commodity production, street traders, and itinerant petty traders (pedagang keliling). BMR administratively consists of two areas: the district (kabupaten) and the municipality (kotamadya). Four research sites were selected within both areas on the basis of “multistage cluster sampling technique” (de Vaus, 1991:67) or the area sampling with multi-stage classification before sampling (Suharto, 1994:31). These sampling blocks include the street, public market, commercial complex, and bus station – areas which typically contain a cluster of street enterprises. The respondents of the research were operators of street vending selected on the basis of place of operations and types of productions. In this study, the nine sites in municipality and district regions were chosen following their main functional activities as shown in Table 2: (a) Market (pasar) owned by local government; (b) Private shopping area (pertokoan) with small and medium-sized shops; (c) Commercial complex with large-sized malls, super-markets, and private business offices; and (d) Public transport station: a transportation destination commonly situated just outside or adjacent to, the street, market or private shopping area. |

Table 2: Number of Street Enterprises

under Study in BMR

|

|

Workshop In addition to the fieldwork, two days workshop involving different stakeholders were also conducted in Bandung in 21 and 22 January 2004. The main aims of the workshop were to disseminate research findings to policy stake-holder and generate policy issues and options with them. In the first day of the workshop, my research project and three papers from BAPPEDAs and IPGI were presented and discussed. In the second day, the workshop mainly focused on identifying alternative policy options on how to integrate street enterprises in BMR). The workshop was attended by 37 inviting participants and 57 voluntary participants. Inviting participants include city administrators (officials of municipal and district development planning boards/BAPPEDAs, municipal and district offices of social affairs, city council, office of market affairs) academia (Bandung Institute of Technology, Padjadjaran University, Pasundan University, Langlang Buana University and the Bandung School of Social Welfare) NGO activists (Kesuma Foundation, Indonesian Partnership on Local Governance Initiative/IPGI, Bandung Institute for Governance Studies/BIGs), mass media reporters (Republika Daily, Pikiran Rakyat Daily, MQFM Radio, Maraghita Radio) and street traders (street trader associations of municipal and district areas). Generally, voluntary participants were bachelor, master and doctorate students as well as lecturers from the aforementioned universities, city dwellers, and street traders from both district and municipal areas interested in the topic. RESEARCH FINDINGS BMR and Street Enterprises Bandung Metropolitan Region (BMR) is one of the three largest urban agglomerations in Indonesia, after Jabotabek (Jakarta metropolitan region) and Gerbangkertosusilo (Surabaya metropolitan region). In 2001, the population of Kotamadya Bandung reached 2.1 million with an average population density of 12,758 people per square kilometre. Whilst, with an average population density of 1,207 the population of Kabupaten Bandung was 3.7 million people in the same year. It is not possible to determine exact statistics for the UIS in Bandung for both kotamadya (municipality) and kabupaten (district) areas, since recent and extensive surveys on this matter are not available. In the case of street enterprises (known locally as pedagang kakilima), however, it is possible to figure out their numbers, distribution, and some main features. In 1999, the Municipal Government (PEMDA) commissioned a survey to explore the basic characteristics of the street trader within its own administrative area. PEMDA estimated that the number of street traders was 32,000 (PEMDA, 1999). Compared to the city population, the vendor density per 1,000 city inhabitants is about 15.2. This means that one vendor serves about 66 people. Street enterprises are agglomerated in specific locations, which are close to places where they can be approached easily and favourably by their consumers. Specific sites for fieldwork were therefore selected on the basis of dominant economic activities and facilities, which contain a pocket of street traders. All locations selected for the study reflect their physical proximity to the main road and also their reliance on activities located on the road. At these locations, public transportation passes along the road at all times of the day and night and there is a considerable volume of traffic. Their locations in relation to both the central city and the dominant economic facilities reveal certain marked differences. However, since all of the nine sites were located in relatively connected urbanized areas, they share many similarities, particularly in terms of their geographic and demographic profiles. Therefore, the analysis towards street enterprises in municipal and district areas were not segregated. The differences will only be spelled out when striking features merit discussion. Business Profiles of Street Enterprises Generally, street enterprises in BMR can be categorised as those selling food (57.9%), trading goods (33.7%), and offering services (8.4%). For example, food vendors include meals, drinks, cigarette, candies. Good vendors consist of those selling personal needs (shirts, towel, spectacles, wallet), basic commodities (toothpastes, soaps, perfumes, candles, lamps) and household wares (beds, tables, chairs, buckets, saucepans). Service vendors may range from “creative services” such as shoe-shining, hair cutting, tailoring, and fortune telling to “repair services” such as the reparation of shoes, watches and clocks, keys, bicycles, lighters, electrics, electronics, umbrellas, and home appliances. In selling a variety of items and services, the vendors are found in various places and structures. The majority of vendors use cart (dorongan) (39%), kiosk (34%) and mat or basket (23.6%) for their wares and operate their business on the pavement, street or roadside (badan jalan), public facility, sewerage and a green area, respectively. Some street traders also sometimes shift and roll their locations from, for instance, the pavement near a school or hospital in the morning to the roadside at the entrance of the square, park, or movie theatre, where crowds congregate at night. The variety of products sold in the street tends to follow a potential market of the products. This seems to reflect that street traders have market awareness. Thus, although the trading in each location encompasses all three kinds of businesses (food, goods, and services), street traders in Kebon Kalapa, for example, are more likely to sell food, since their locations are not far from schools, universities, hospitals, and pick-up station, where food consumers are very numerous. In general, one main factor contributing to the large number of street vendors in BMR is economic: the high demand for lower price items. The reason that city inhabitants purchase food, goods or services from street enterprises is because the prices of most street products are always lower than those for restaurants, shops or supermarkets. Almost all strata of the community were observed to purchase items from street vendors. However, the main consumers generally come from middle to lower classes, from schoolteachers to taxi drivers, from office guards to becak (pedicab) drivers, and from office clerks to construction workers. Street vendors ensure that everyone gets a bargain and that different consumers are offered items of reasonable quality and at affordable prices. Most street traders in BMR are conducted by men (71.3%) who operated their business during the day (78.7%), night (3.4%) and day and night (17.4%). Of the 178 street traders, 37.1 percent had achieved Junior High School (12 years schooling), followed by 34.8 percent and 22.5 percent of those who completed Primary Education (9 years schooling), and Senior High School (15 years schooling). For very small enterprises, the amount of capital needed to start and operate a business varies considerably from activity to activity, and the larger and more technically skilled the establishment, the higher the demand for capital (see Suharto,2002). For example, street traders offering services such as hair cutting and shoe-shining require little initial and working capital, while traders operating a street restaurant, or selling clothes, shoes, and fruits need substantially more. Based on the mean value of the stock, the average working capital of the street vendors was estimated to be slightly above Rp.1,500,000 or calculated at the rate of $ 1= Rp.8,000, about $187. Sources of capital for these small enterprises typically come from informal schemes such as from family (47%) and moneylenders (23%). Family businesses are critical elements in the economy of street enterprises. In most countries the UIS, notably street trading, is a family business and hence a larger circle of family or kin labour is essential to the functioning of the street establishment (Tinker, 1997:154-5). The information about the source of capital demonstrates this pattern of family business. It shows that most establishments derived capital from informal schemes such as from family (55.6%) and relatives (7.3%). In terms of trading revenues, most street traders seemed to have no difficulty to remember expenditures and profits although they do not keep written records on their cash flow. After weighting up their answer against the observed daily cash flow, it was found that the vendor’s daily average profits were about Rp. 53,686 ($6.7) placed their revenues up to Rp.1,610,580 ($201) per month. The findings appear to show that street traders make a reasonable profit from their trading. This earning is substantially higher than the poverty line established by the World Bank of $1 per day per capita. On a monthly basis, this earning is also well above the standard minimum wage of formal employment, known as UMR or upah minimum regional (regional minimum wages) of nearly Rp.500,000 per month ($62.5). Several studies revealed the same pattern as this finding that, on aggregate, the incomes in the informal sector were comparable to those in the formal sectors and even superior to some of them (e.g. Thomas, 1995, Tinker, 1997). Tinker’s study (1997:174), for example, revealed that while street food traders in Thailand earn incomes that are relatively higher than the lower to middle ranges of waged employees, in Pune, 75 percent of the traders earn an income above the official poverty line for a family of four – although 15 percent of the traders achieve this level by combining vending income with other sources – and 10 percents of the traders earned income below the poverty line (see also Suharto, 2002a, 2002b) After this information about socioeconomic background of street enterprises, the rest of the paper is dealing with the reasons of the business operators to participate in trading and for selecting worksites. Understanding these variables is very important to know the motive behind their participation in the business, as well as to provide additional information about the history of business activities. This information can be used to underline policy alternatives in integrating the UIS into urban planning. In this regard, street traders were asked to express their opinions on the nine areas of reasons of participating in street enterprises (Table 3) and ten factors determining their selection of worksites (Table 4). Five attitudinal scales (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree) were used to measure the response toward corresponding items with response range was 1 to 5. Socioeconomic Reasons to become Street Traders The majority of respondents perceived that they participate in street trading because of the difficulty of entry into the formal job sector (4.11) or alternatively, due to the ease of entry into street trading (3.78). In order to obtain some incomes, it is relatively easy to start and operate the business. They can, for example, adjust it to their knowledge and skills, or they can operate it by following their predecessor through kinship networks. As to the rest of the variables (questions number 6 to 9), their low average mean (2.15 and 3.25) may indicate that these reasons have had relatively less influence on their decision. It is interesting to note that that although their return level is higher than the poverty line and is relatively favourable in comparison to other available and accessible alternative sources of income, they perceived that street trading is not a job that provides adequate income and high social status as shown by the average mean scores of 2.91 and 2.15 respectively.

|

|

Table 3: The Reasons to Participate in Street Enterprises

Table 4: The Reasons for Selecting Worksites

|

|

This may be caused by the fact that the poverty

line and regional minimum wages are actually very low. They are set out on very

basic physical needs (calorie intake) and does not take into account social

needs, such as education, health and housing. As a result, while those who have

incomes below poverty line and are unable to purchase their basic needs can be

labeled as being extremely poor or destitute, those who are able even to meet

the costs of the basic necessities cannot automatically be labeled as “not poor”

since their incomes are still in the lower tail of the income distribution of

the country. They are still likely to face problems of overcrowded housing, lack

of access to transport and recreation facilities, which, although not being

life-threatening, represent deprivation compared to the rest of the population.

Factors Influencing the Selection of Worksites The result of the analysis presented in Table 4 show that the best location to attract customer appears to be the most important factor influencing their location for business activities. This is followed equally by availability of access road (3.71) and lack of alternative sites (3.71). The table also shows that avoiding harassment from security, security of tenure or plot, and proximity to house are important for street traders’ decision in selecting their workplaces. This information reveals that although street traders were widespread in many different places, their locations always reflected their reliance on economic activities which were either located on, or affected by, the street. Thus, while many street enterprises may clearly be drawn from the main roads or intersections, some of them clogged sidewalks or pathways reflecting their physical proximity and access to the streets. They know how to sell and make profits by selecting only those strategic locations where demand for their products is high. As elsewhere, the popular image of street vendors in BMR finds them agglomerating around potential business locations. In Jalan Dewi Sartika, Pasar Baru, and Kebon Kalapa, for example, street enterprises surround the market (pasar), shopping area (pertokoan), and commercial complex trading food, commodities, and services to city dwellers. In Leuwipanjang and Terminal Banjaran, on the other hand, street vendors were found at and nearby the bus and pick-up stations selling products to travellers and drivers. In addition to these locations, the street traders, mainly food sellers, were also observed at the entrance of schools, universities, and hospitals, providing food to their customers, such as pupils, students, patients, staff and visitors (see Suharto, 2002a). EXISTING POLICY MEASURES AND LEGISLATIONS Document study and discussions with city

administrators, academia and NGO activists through interviews and workshop

highlighted that policies toward street enterprises in BMR are permissive in

nature. Referring to model of policy approaches discussed in the literature

review, the major type of policy intervention to deal with street enterprises

can be categorised as locational. It emphasises policies of restriction and

relocation. This form of intervention generally ranges from Model B (allow

hawkers to sell legally from some of their locations but remove from others to

public markets or approved “sites”) to Model C (relocate hawkers in locations

chosen by government authorities). Examples of the actions can be summarised as

follows:

In BMR, like in other cities in Indonesia, cities are administered under the local government office (kantor PEMDA) and headed by a mayor called bupati for district area and walikota for municipal area. There is no special department or division in the PEMDA office having direct responsibilities to manage street vendors. PEMDA office is a coordinating body through which policies are distributed to a series of sectoral offices or departments, such as Satuan Polisi Pamong Praja (Public Security Office), Kantor Sosial (Office for Social Affairs), Dinas Pasar (Department of Market Affairs), PD Kebersihan (Office for City Cleanliness), and Dinas Kooperasi dan UKM (Department of Cooperative and Small-Scale Enterprises Affairs). Amongst the above agencies, the Public Security Office appears to be the most powerful with respect to street vendor activities. It is entrusted with enforcing law and order within the city and the one primarily responsible for clearance operations against street enterprises. Thus, while in administrative terms policies on street vendors are complicated, the policies toward street enterprises are the concern of many departments and mainly concerned with law and order, traffic regulation, and city cleanliness. In Bandung Municipality, street traders are organized by APPKL (Asosiasi Pekerja dan Pedagang Kaki Lima) or Association of Street Traders and Workers which is now headed by Mr Iwan Suhermawan. Representatives of the association invited to participate in the workshop revealed that although not all street traders in Bandung become members, the association has been active in promoting and channeling the interests of street traders in a particular location. The primary concerns of the association are to keep the market and working conditions clean and orderly as well as to provide a good means of complaining injustice and harassments from public security officers who often perform street clearance operations without fair notification and consideration. The association of street vendors was reported to be fairly powerless against the government. It appears that social change organisations and advocacy groups, such as NGOs, grass-root activists, mass media groups, and some political parties lack commitments to back-up and promote street vendors interests. Generally speaking, the implementation of policies towards street vendors are not successful. As mass media reported, the recent clearance operation of street vendors in seven points of the Bandung City are questioned. There is a question on the costs of the operation and its sustainability in the long run (Republika, 2003, Pikiran Rakyat, 2004). There is also a question on the process of the policy making. Discussions with street traders, academia, NGO activists as well as city administrators revealed that the policies were initiated and developed without consultation with street vendor representatives. Many argued that the development of policies towards street vendors contains bias from private car owners whom are considered as the dominant interest group to feed into and influence the policy making. They generally only see the disadvantages of street enterprises operations and perceive the congregation of the UIS as the main cause of traffic congestion. Therefore it is not surprising that the main tenet of the policies is not to integrate the street vendors into the urban planning, but rather to abandon them from it. CONCLUSIONS The findings of this research paper have basically described profiles of the study area and respondents of this study. The description on profiles of the study area provided a review of BMR, its economy and its inhabitants. Features of urban development in the region reflect several important patterns of development trajectory occurring in other metropolitan regions, such as Jakarta Metropolitan Region (Jabotabek) and Surabaya Metropolitan region (Gerbang Kertosusilo), and more broadly in the national context. The economic and social development in Bandung has contributed to the level of industrialisation and urbanisation in which the contribution of agricultural sector to the BMR economy is decreasing, released by trade, manufacturing and service sectors. In BMR most street traders were found to sell foods and operate on the streets adjacent to market, private shopping area, commercial complex and public transport stations. Although the types of products are varied, they generally consist of food, goods and services. The principal finding on the enterprise characteristics of street trading reveal that with many street vendors obtaining some kind of benefit from kinship networks, especially source of capital, the largest enterprise category of the street vendors can be referred to as a family establishment. As a family enterprise, street trading in BMR involves kin relationships in its history of business activities as well as in its production processes and employment characteristics. With reference to income earnings, it seems likely that most street traders are not living in poverty and that they are not the poorest of the society, especially measured by the poverty line of $1 a day. While in aggregate and average most street trader incomes are higher than the poverty measure, on the basis of the regional minimum wages, street trading provides a favourable source of income compared to the low skilled formal sector and other visible alternatives, such as unskilled construction workers. The main factors determining the reasons to involve in street trading is lack of job opportunity in the formal sector. This is followed by the reasons that it is easy to start, as well as to operate street enterprises, and that the UIS is a job suited to knowledge and skills of the operators. On the basis of the factors influencing the selection of sites, the urban informal street vendors in BMR perceive that business location should be attractive to customer and have access to main roads in order to offer wider markets. Dealing with street traders, it is clear that policies need to be sensitive on characteristics and aspirations of street enterprises in BMR. The policy should not degrade their income earning opportunities. For example, if the government plans to provide alternative works, they should be easy enough to start and be operated, and that the jobs should be suited to knowledge and skills of the operators. If the policies are to provide alternative sites, best location to attract customers and availability of access road should be amongst the important considerations. Other considerations that should be taken into account are that they should be harassment-free from security officers, that they should have security of tenure, and that the operator should have proximity to house. The existing policies toward street enterprises in BMR are partial, permissive and elitist in nature. The polices emphasise restriction and relocation and do not take into account the characteristics and opinions of the population. Regulating and monitoring the operation of street enterprises encompassed by term “locational policy” can by no means solve the problems associated with the street business activities. Therefore, government authorities and urban planners should recognise the need to accommodate the UIS in the urban policy-making. Rather than excluding them from the urban economy, there is a need to shift the policy paradigm from locational evictions to educational and structural integration. In sum, policies that specifically address and are responsive to the interests of the UIS is of particularly paramount in the urban policy making. These policy issues and recommendations are discussed further in the policy paper.

|

|

REFERENCES

|