|

|

|

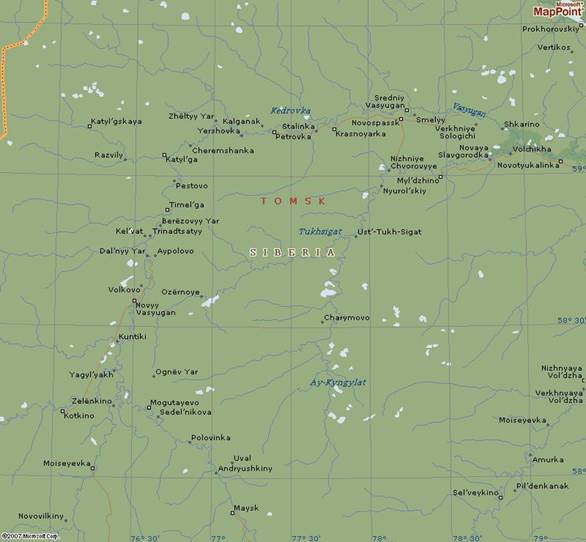

Vasyugan

is the western tributary of the Ob river

in the middle of the western Siberian Plain east of

the Ural mountain range, in the Kargasok

district of Tomsk region. The

low-lying local landscape consists of a multitude of rivers and lakes,

which drain the world’s largest bog lands – the Vasyuganskie Bolota (Vasyugan

swamp). The general climate and ecosystem of the Vasyugan basin is

typical for western Siberia, characterised by an

extreme continental climate, with temperatures ranging from +30C'

in the short summer (May-August) to -40C' in the long

winter

(October-March). Local fauna include bear,

elk (moose), deer, wolves and a range of

other fur-bearers and wildfowl. Traditionally, much of the Vasyugan

Khanty diet consisted of fish. Such species as pike, bream, perch, starlet among other species are a frequent catch locally. In contrast to other Khanty groups, the Vasyugan

Khanty had no local tradition of

reindeer husbandry due to the specifics of local ecology, dense mixed forests lacking reindeer pasture, numerous streams, rivers, lakes and vast bogs.

|

|

Traditionally the Vasyugan Khanty were subsistence hunters and fishermen. Their low scale seasonal migration were motivated primarily by

the main

occupations, hunting and fishing, and consisted of repeated trips from the permanent riverside

village out to the clan hunting

territories in October-December and January-March, followed by downstream migrations to family-owned

fishing locations. The hunting grounds are traditionally equipped with

one or more small hunting cabins with storage huts elevated above the

ground on poles; whilst at summer fishing locations families would build

makeshift tents and shelters using birch bark and poles. The routines of

seasonal mobility were also reflected in the traditional calendaric

terms. These names do not equate directly

to European notions of months, and may vary in length, both from one

period to the next, but also from one year to the next depending of

climatic, ecological or other practical factors. As a result, these concepts map sequences of behaviours, rather than purely temporal notions. Each season had a common lexical component of iki 'loose equivalent of ‘moon’': körek-iki ‘time

of eagles’ (~March); urn-iki

‘time of crows’ (~April); lontwäsek-iki

‘time of geese and ducks’ (~May); pojaltew-iki ‘time of the snow crust’ (~December), etc (Filtchenko, 2000-2005; Tereskin, 1961; Gulya, 1965; Sirelius, 2001;

Lukina 2005; ).

|

The prevailing majority of the

traditional Vasyugan Khanty permanent settlements (yurt (local topology term of Turkic etymology), puɣol (native

Khanty term) are located along the Vasyugan River, in widely-spaced pattern, often several hours and days by

boat from one another. Exceptions to this pattern include occasional

settlements on the shores of the region’s major lakes. This settlement pattern of extended family villages reflected the structure of traditional

social organization which was based on patrilocal, patrilineal exogamous

lineages.

The native reference term used for

this social grouping is aj puɣol jaɣ 'same village people'. The word

puɣol "village" normally refers the typical Khanty settlement of 2-3 huts at the river or

lake edge, and housing a small community of 10-15 people. Besides more localised clan and lineage identities, historical accounts (Haruzin, 1905; Sokolova,

1983) suggest that the Vasyugan

Khanty were aware of larger social, localised

‘ethnic’ groupings, mainly on the grounds of linguistic affinity. These groupings referred to the major rivers the group occupied, äs’ jaɣ 'Ob-river people', waɣa jaɣ Vakh-river people', wat’ joɣen jaɣ 'Vasyugan-river people, and at a larger level yet, eastern Khanty groups describe themselves as qanteɣ jaɣ 'Khanty people' - a compound term combining the ethnonym for eastern Khanty qanteɣ ‘Khanty’ (distinct phonetically from the western Khanty self reference

term xanti 'Khanty') and the term jaɣ with the general sense 'people' (Tereskin, 1961).

More detailed descriptions of Vasyugan Khanty kinship and social organisation can be found in (Kulemzin and Lukina 1976; Filchenko -

forthcoming).

|

|

The Khanty of Vasyugan are confident

that their ancestors have long resided on these territories and refer to

them as äreŋ jaɣ meaning 'ancient people', who, according to folklore, were in frequent conflict with Tatars (qatan’ jaɣ), which is evident, in folk

interpretations, from archaeological sites in the landscape, including the remains of

fortified settlements, scatters of metal arrow heads and occasional swords and pieces of body armour.

The ancestors,

occupants of these sites were the warrior-hero progenitors of the Vasyugan

clans, who lived in the region and defended it from attacks and

occupations by Tatars from the South and Nenets (joren jaɣ) from the North (Lukina, 1976).

The rich spiritual life of these

communities was the object of description by late XVIII - early XX century travelers and ethnographers (Sirelius 2001; Karjalainen 1921, 1922).

The life of all Khanty and animals was created and predestined

by torem, a chief deity. Another

ultimately powerful deity is the female mother-spirit puɣos äŋki, the giver of life and soul (il), and judge of its length

and quality (Karjalainen, 1927). There are also numerous powerful masters of elements: the water/river

deity äs’ iki, the master of fish and a multitude of water spirits

and demons; the forest deity wont iki, the master of animals and

birds and of the forest spirits.

The Vasyugan Khanty also used to keep images of

so-called home or family spirits (juŋk) which were linked to

the welfare

of individuals and families, success

of hunting and fishing. Dated accounts

describe the events when the spirits were sat at a table

and offered food, typically by a man, before hunting and fishing seasons,

to give luck and rich spoils. Various locations along the Vasyugan river were known as homes of a variety of local spirits, mostly of anthropomorphic nature, in the shape of a

woman or a man, and in having wooden

figures representing their image.

The sacred sites, “homes” of the spirits continue to be distinct and

known to local families and regularly attended for offerings and paying

respects. For Vasyugan Khanty, it was also typical to have anthroponymic

group-names (Vertesh 1961, Lukina 1978) typically corresponding to the names of the clan progenitors: kotʃet

'badger', kötʃerki

'chipmunk', köraɣ 'sack' (Filtchenko, 1998-2005).

The sacred rituals were typically performed by the hunters themselves, however, often

the shamans (jolta qu) were invited to make offerings to the spirits

and ask for rich spoils in hunting/fishing, but more typically to act in the role of

medicine men and fortune-tellers (Dmitriev-Sadovnikov, 1911; Karjalainen,

1922; Zuev, 1947; Kulemzin, 1976). The unique role of shamans was their

ability in the process of shaman rituals to part with their body and

‘walk the worlds’ (lower or upper) and to communicate and interact with

spirits and deities, act on other people’s souls/spirits, and foresee the

future and help build the strategies for successful hunting, as well as

to foresee

the individual hunters' fate. In case of

illness treatment, the shaman’s spirit was typically expected to travel

to the lower world to find and return the stolen spirit of the ill

person. Alternatively, the shaman was understood to heal the person by

expelling the spirit of illness from the body of the ill, fighting it in

the spiritual realm, often in alliance with either the family/clan spirit

or the local patron spirit (Kulemzin, 1984). Shaman’s skills were combined the intimate experience with the whole pantheon

of spirits and deities, as well as general close knowledge of the local landscape, flora and both behaviour of

and towards animals.

|

|

|

The first Russian contacts with Vasyugan Khanty date back to XVI

century at which time they had resided at this location for at least 3 to

10 centuries based on archeological research. Before the Russian contact, Vasyugan Khanty are assumed to

have been in contact with Siberian Tatars, as the area was under

administrative control of Siberian Tatar Khan. Based

on available folk data, language/culture contact with Tatars and among

other local ethnic groups was fairly limited, with inter-ethnic relations

generally described as hostile.

Early Russian colonial policies were conservationist with

minimal Russian language contact and assimilative pressures, with the

exposure to Russian growing considerably in the end of the XIX century and

increasing radically in 1930-1960s as a result of the soviet

collectivization and forced migration (exile) policies. Since 1960s-1980s

most of the area was heavily assimilated due to policies of social

engineering, mandatory secondary schooling (Russian media boarding schools)

and particularly by the mineral resource exploration programs resulting in

considerable influx of non-native population from European Russia, Ukraine and

central-Asian regions.

The language of Vasyugan

Khanty was much lesser described in occasional sketches and word

lists (Karjalainen 1913). For the Vasyugan

Khanty language the situation of neglect and discrimination has been

a reality. Speakers are ridiculed by the mainstream majority, children are

not taught, and in some cases persecuted for speaking Khanty at schools. The

common ethnonym ostyak is perceived as pejorative, while the

stereotypes about Khanty in general public

remain uninformed. All Khanty speakers are bilingual

with Russian being the language of daily communication across ethnic

groups. Khanty

language undergoes a steady decrease of the functional sphere,

reserved primarily for occasional family use, rare peer communications and

extremely rare traditional religion (shamanism) contexts.

The majority of Vasyugan Khanty are currently

linguistically assimilated Russian monolinguals numbering under 150 pers.

The numbers of Vasyugan Khanty officially

registered vary from source to source, however, based on the original research

there are around 20 Khanty who permanently reside on Vasyugan

river and have practical knowledge of traditional language and culture.

They are bilingual minority native language speakers, all over the age of

50. The number of semi-fluent speakers, capable of maintaining restricted

basic conversations in Khanty does not exceed

50, principally placing these dialects in the group of languages in the

imminent danger of extinction within a single generation.

|

|

References:

Chernetsov, V.N. K istorii rodovogo stroja u obskix ugrov. SE, VI,

VII.

Dmitriev-Sadovnikov, S reki Vakha, Surgutskogo uezda. ETGM, V-19.

Tobolsk. 1911.

Filtchenko, A.Y. Field notes from ethno-linguistic research of Eastern Khanty. The Field Archive of the Laboratory

of Siberian Indigenous Languages at TSPU. Tomsk.

Haruzin, N. Ethnography. V-IV. Verovania. 1905.

Jordan, P. & Filtchenko A. Continuity and Change in Eastern Khanty

Language and Worldview. In: “Rebuilding Identities: Pathways to Reform in

Post-Soviet Siberia" edit. Erich

Kasten. Dietrich Reimer Verlag 2005.

Karjalainen, K.F. Die Religion der Jugra-Völker. Parvoo. 1927.

Kastren, M.A.

Puteshestvie po Laplandii, Severnoj Rossii i Sibiri. Moscow. 1860.

Kulemzin V.M. Semja kak faktor socialnoj stabilnosti v tradicionnom

obshestve, in: Voprosi Geografii Sibiri 20: 1993.

Kulemzin V.M. Celovek i priroda v verovanijakh Khantov. Tomsk. 1984.

Kulemzin V.M., Lukina N.V. Novije dannije po socialnoj organizacii vostochnih

hantov, in: Iz istorii Sibiri, vip. 21, Tomsk. 1976.

Kulemzin V.M., Lukina N.V. Vasjugansko-vahovskije hanti, Tomsk. 1976.

Kulemzin V.M., Lukina N.V. Znakomtes’: Khanti. Novosibirsk. 1992.

Kulemzin V.M. Mirovozzrencheskie aspekty ohoty i rybolovstva. In.

V.I.Molodin, N.V.Lukina, V.M.Kulemzin, E.P.Martinova, E.Schmidt,

N.N.Fedorova (eds.) Istoria i kultura Khantov. Tomsk. 1995. pp.45-64.

Lukina, N.V. Nekotorie voprosy etniceskoj istorii vostocnyx xantov po

dannym folklora.//Yazyki i Toponimiya. Tomsk. 1976.

Lukina N.V. Voprosi etnografii vostocnix xantov v svete novix

dannix.//Acta Ethnographica Hungarica, 43 (3-4): 1998. Budapest.

Lukina, N.V. Obshee i osobennoe v kulte medvedja u obskix ugrov. // Obrjady

narodov severo-zapadnoj Sibiri. Tomsk. 1990.

Lukina, N.V. Istroia izuchenia verovanij I obrjadov. In. V.I.Molodin,

N.V.Lukina, V.M.Kulemzin, E.P.Martinova, E.Schmidt, N.N.Fedorova (eds.)

Istoria i kultura Khantov. Tomsk. 1995. pp.45-64.

Lukina N.V. Khanti ot Vasyuganya do Zapolyarya. T-I. TGU. Tomsk.

2004.

Lukina N.V. Khanti ot Vasyuganya do Zapolyarya. T-II. TGU. Tomsk.

2006.

Sarkany Mihaly. Female and Male in

Myth and Reality, in: Uralic Mythology and Folklore, Bp., Helsinki. 1989.

Sirelius, U.T. Puteshestvie k Khantam. Tomsk. TGU. 2001

Sokolova,Z.P. Sotsialnaja organizatsija hantov i mansi v

XVIII-XIXvv. Moskva Nauka. 1983.

Startsev, G. Ostyaki. Moscow.

1928.

Steinitz, W. Dialektologisches und etymologisches Woerterbuch der

ostjakischen Sprache, Lief.1,2-3, Berlin. 1966.

Tschernetsov W.N. Bärenfest bei den Ob-Ugriern. – Acta Ethnographica

Academiae Sceintiarum Hungaricae, t.23 (3-4). Budapest, 1974.

Tyler, S. Cognitive Anthropology. Waveland. 1969.

Vertes, E. Beitrage zur Methodik der ostjakischen

Personennamenforschung.//VI Internationaler Kongress fur Namenforschung.

Bd.III. Munchen. 1961.

Zuev, V.F. Opisanie zhivushchix v Sibirskoj gubernii v Berezovskom

uezde inoverceskix narodov ostyakov i samoedov. Moscow. 1947.

|

|