State Capture and Misgovernance as Causes of Widespread Corruption in Serbia

Draft

Vesna Pesic

October 2006

Introduction: The Rise of ‘capture state’ and large scale corruption

Large-scale and systemic (political) corruption has acquired such proportions in Serbia that it may undermine the success of its transition. I have identified the phenomenon of state capture as the key cause. Literature defines state capture as the ‘seizure’ of laws to the advantage of corporate business via influential political links in the parliament and government. I have defined it more broadly as any group or social strata, external to the state that seizes decisive influence over state institutions and policies for its own interests against the public good. I will show that in Serbia, political parties are the main agents being used to appropriate the state and public assets. They are systematically expanding their political and financial power, influence and ability to employ their relatives and party cronies, and promote the personal and corporative interests of the political and economic elites in control behind the scene. The appropriation of state institutions and functions by the political party leadership is being carried out by the use of a variety of mechanisms which I will explain using my research data. How citizens of Serbia perceive the role of the parties in state capture and corruption will be presented using a survey of public opinion conducted specifically for this policy paper. I will conclude by presenting a list of policies that should be applied to reduce or neutralize the captured state phenomenon.

The Extent of the Problem:

During the first two transition years after the overthrow of Milosevic in 2000, political corruption in Serbia declined. The government was not the centre of corruption as it was in the previous regime. [1] When the first democratic Prime Minister was assassinated and his government was forced to resign under the pressure of “old forces”, political corruption at the highest level was renewed. With the newly elected government in 2003, corruption began to reach alarming proportions – a trend that has continued the past three years. This increase in corruption is corroborated by the World Bank report on patterns and trends of corruption in all transition countries in the 2002-2005 periods.[2] The research shows that some transition countries have recorded continued success in fighting corruption (Georgia, Slovakia, Romania, Bulgaria and Croatia made headway with regard to all dimensions, while Moldova, Tajikistan, The Ukraine and Latvia made progress along some dimensions). On the other hand, some countries, including Serbia, Albania, the Kyrgyz Republic and Azerbaijan, suffered an increase in corruption after 2002 with respect to monitored indicators. Serbia has suffered both an increase in “petty” i.e. administrative corruption (bribery) and in the topic this paper deals with - state capture - which is qualified as “grand and systemic corruption” rooted in political corruption and uncontrolled powers of the political elite. With regard to higher levels of state capture, Serbia has found itself in the same group with Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina and the FYR of Macedonia.

The Serbian citizens’ perceptions of corruption coincide with the WB research results. The data of the survey conducted for this policy paper (see Annex I) show that Serbia’s citizens think corruption is widespread and that it has increased in recent years. When asked about the proportions of corruption, only 3% of the pollees think it is minor, 34% qualify it as considerable, while 53% perceive it as widespread. As many as 56% of the respondents think corruption has risen in the past two years, while merely 19% are of the view that it has decreased (the rest had no opinion). The answers to the question during which government has corruption been the greatest yielded similar percentages: 51% said it was never greater than in the Milosevic era, while 25% said it was the greatest now. Only nine percent think corruption was at its highest during the first post-Milosevic government (led by Prime Minister Djindjic) and 5% think it was the highest when Prime Minister Zivkovic led the same government after Djindjic’s assassination.

Following the transition in government there was a distinct change in priorities leading to a weakening of public anti-corruption policy and a rise in corruption. Whereas the first Djindjic Government[3] ambitiously and enthusiastically concentrated on enabling Serbia to integrate with the EU as soon as possible, enthusiasm for the EU integration process noticeably ebbed after the second government came to power. A rightist clerical-nationalist party has played the leading role in the coalition government set up after the December 2003 parliamentary elections.[4] Adverse to Western values, it has placed commitment to EU integration on a back burner.[5]

Although the second transition government has passed a number of anti-corruption laws,[6] no institutional reforms have been introduced to ensure accountability, transparency, rule of law, public sector effectiveness and merit-based public office appointments. Rather, it has focused on reviving nationalist values, resolving the “Serbian national issue” and preserving the staff and corruptive institutional structures that better serve such objectives. Reforms of the state institutions have merely been rhetorical. Insufficient encouragement has been given to the competitiveness of the economic and political systems. New laws and decrees have extended discretionary decision-making methods. The transformation of state property (public companies) has been curtailed. The effectiveness of regulatory institutions has been sabotaged and the implementation of the law on auditing state institutions and the Law on Ombudsman has been delayed. The Anti-Corruption National Strategy passed in December 2005 still lacks an institutional framework; specific action plans have not yet been drafted.

The weakening of the European orientation of the Serbian transition has been accompanied by the rebuilding by the political and business elite[7] of ’state capture’ mechanisms. They have been able to “seize“ control of state institutions, exercise excessive influence and amass considerable wealth. The phenomenon of state capture has been responsible for the growing large scale corruption and has seriously jeopardized public interest and transition in Serbia. Although transition in the economic sphere, mainly on the macroeconomic level and privatization has continued, institution building in political, judiciary, and administrative systems has been delayed, creating the opportunity for state capture.

The visible consequence of the deficiencies described above have been the continual on-going corruption affairs appearing in the news during the past three years. All cases have been at the ministry level. The greatest number have been connected with the „finance party“ (G17 Plus). Scandals have included: the privatization procedure of the National Savings Bank[8]; a bribery situation publicly known as the “Brief case affaire“ involving the vice governor of the National Bank of Serbia; the gross manipulation of a mineral water company privatization; graft in army procurement and the unauthorized purchase of a satellite for monitoring Kosovo. Other cases of suspected corruption having potential million-dollar damages for society involve the import of electricity (owners of the import company are said in public to be financiers of the bigger political parties), the import of petrol from Syria and the buying of railway cars without tender and procurement procedures. [9]

None of these affairs has been resolved by legal processes. The president of the Council Against Corruption, the only official institution dealing with this problem, has estimated recently that the level of corruption in Serbia is once again at the level before October 5 (when Milosevic was in power). She pointed out that during the last three years there has been no audited Final Budget Statement. She warned the public that the National Investment Plan (NIP) launched by the Minister of Finance and supported by the Government has been passed in a corrupt manner - without law for its implementation and control - by avoiding legal procedures and by giving discretional decision-making to a group of ministers. She predicted that the corruption in the country will rise significantly if the NIP is to be implemented.

Recent events related to the preparation, approval process and content of the new Constitution of Serbia confirm my initial hypothesis about ’capture state’ by the political/party elite. In mid September 2006, leaders of the four biggest parties[10] agreed literally over night[11] about the Constitution Proposal. Without one day of public debate, based on the decisions of the party leaders, Parliament passed the Proposal and called for a referendum for its approval. Even the members of the Parliament never received the Proposal, nor did they have a chance to discuss it in session when adopted. Citizens and their organizations did not have chance to debate it either. Among items that reinforce capture state mechanisms of the political parties in the Constitution Proposal, MP mandates belong to the parties . In addition, the immunity rights for the MPs have been broadened. These changes will strengthen political power of the party elite and its interests (i.e. executive power) and additionally degrade Parliament and the MPs’ responsibility to the constituent’s interests by re-confirming their impunity. In the public, the new Constitution is named the „Functionary’s Constitution“ because it will reinforce party domination over the state.

The new Constitution will not help curb ‘capture state’ and its damaging consequences. It will not make political leadership accountable to the public. Even worse, judicial independence is not guaranteed by preventing party/political influence over the police, the courts and public prosecution bodies. Getting to the roots of corruptive practices in governance is crucial to Serbia’s ability to break the grip of rigid institutional structures constructed to protect vested interests and proceed successfully in the European Union enlargement process. However, these two clear mandates in the new Constitution will make it difficult to eliminate the parties’ use of public offices for their private interests rather than for representation of constituents’ interests and the pursuit of the public good.

I. The Capture state Model in Serbia and its mechanisms

From the point of view of system theory, capture state is caused by weak functional differentiation of the social system. Boundaries between the subsystems do not exist or are porous. Power and goods from the economic sub-system are convertible for influence and goods from the political sub-system and vice versa, depending on where the dominant power of the social system lies. The dominant power in Serbia is still located in the political system.

The most important ’capturing’ agent are the political party leaderships who have seized huge state property including public companies, public offices and institutions for their own interest. The second important agent are the 10-15 richest tycoons of the country who finance all the relevant parties. Both elites in collusion with each other have established a system of integrating their influences, interests, and services for mutual gain. This collusion has created an oligarchy social structure in Serbia that undermines effective institution building and the rule of law. The main chains of influences and interests connection are demonstrated in the Model of State Capture in Serbia (Picture1).

Picture 1: Model of State Capture in Serbia

Picture 1 above shows the mutual dependence between the political and business elite and how the tycoons help sustain their political positioning by financing all of the relevant parties; in return, the ruling parties protect economic markets, fix tenders and auctions, and pass favorable legislation for the tycoons. It also shows how Government, Parliament and Parties are connected with public companies and public institutions as their own share of power.

The Mechanisms Used:

The following analysis will concentrated on ’state capture’ as a specific process in which political elites gain control of public offices, enterprises, utilities, and resources through a mingling of state, political party, and economic power. Emphasis is placed on the concrete mechanisms which explain how political parties impose their own benefits over public interest, how these mechanisms are incorporated in the mulity-party system and how the party-state amalgamation has been achieved.

I have selected the following six interconnected mechanisms of state capture:

1) Division, of the government and the entire public sector into a feudal type system whereby each party in the ruling coalition is given control over the portion it receives (based roughly on the number of MPs it has in parliament) as if it were its own private fief. [12]

2) Connected with the first, the second mechanism entails appointing leading party officials (presidents, their deputies, etc) to manage the ’fiefs’ although they are simultaneously actively discharging their party offices. Because the party leader – feudalist has MPs in the Parliament providing majority support to the Government, corruption is practically incorporated in the manner in which the government operates.[13] If a minister were to be dismissed for corruption, he would withdraw his MPs and the Government would lose the parliamentary majority and fall.

3) Degradation of the Parliament and the mechanism used for bribing MPs assuring their loyalty. Obedience is obtained by offering them multiple functions such as being appointed to the managing boards of the public companies or appointed to perform executive functions in local and regional governments, enabling them to receive several sources of income.

4) Parties in the ruling coalition have the exclusive ’right’ to make appointments in state administration, public companies, utilities, institutes, agencies, funds, health, social and cultural centers, dormitories, veterinarian stations, schools, theatres, hospitals, libraries, monuments and memorial parks maintenance services – all of which belong to the public and are supported from the public budget. Management positions are not advertised and based on merit, which additionally damages public interests and constitutes widespread discrimination of citizens on the basis of party affiliations.

5) The relationship between parties (government) and business is not regulated in a transparent manner because the Law on Funding of Political Parties, passed in 2003, is deficient and its implementation did not diminish corruption in this area. The parties have remained the center of the corruption.

6) Political influence over the judicial system is excessive, and there is a lack of checks and balances between the three main state powers. The executive branch (which again means party influence) has gained control over the Parliament and the courts. This key mechanism is an extremely-extensive, separate topic which must be investigated in-depth independently, and it will therefore not be part of this research.

II. How the Government Functions as a Confederation of Party „Feuds“

I will analyze the party feudal system at the national level by presenting details about the cases of the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Education and Sport. I will then describe how the party feudal system functions at the local level by presenting the case of Novi Sad.

The Feudal/Party System at the National Level: The Cases of the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Education and Sport

At present, in Serbia, the ruling coalition is composed of 4 parties[14] so the distribution of ’fiefs’ is the following:

|

Party |

MPs |

Ministries |

Quotas in Public Companies (managing positions) |

|

DPS |

53 |

10 (11) |

50% |

|

G17+ |

34 |

4 (3) |

30% |

|

SRM-NS |

22 |

5 |

20% |

|

SPS |

20 |

- |

Quota of DPS |

The coalition agreement sets the percentages of public offices that each ruling party receives in accordance with the number of seats won in the Parliament. The second part of the agreement has had a direct impact on the growth of corruption during the last three years. This aspect was not present in the first post- Milosevic government[15]. It focuses on the content and classifies all offices by portfolios (horizontally and vertically). State capture and monopoly constitute part of the division – each coalition party receives a number of related portfolios to manage and staff by itself. Power is thus feudalized – each ruling party is the absolute ruler of its own ’fief’ and the government is now operating as a confederation of ’power fiefs’.

How the ‘Feudal System’ Functions in Practice.

The strongest party (the DPS) with 53 MPs controls 10 ministries (plus the Ministry of Defense, after the dissolution of Serbia and Montenegro). This party exclusively controls appointments in the two most powerful “institutions of authority“: Internal Affairs (the Ministry of Police and Intelligence Agency) and Economic Affairs (two ministries: one for the internal economy and the other for International Economic Relations). In the same manner, this party holds the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Science, the Ministry of Education and Sport, the Ministry of State Administration and Local Self-Management, the Ministry for Religion and the Ministry of Energy. As the strongest party, the DPS manages the largest monopoly companies, like Telecom (and the telecommunication system), PTT (the Post Office, Telegraph and Telephone Company), “Galenika“(the biggest pharmaceutical company whose director is vice-president of the DPS), Yugo- Import (an arms-trading company) etc.

.

G 17 Plus exclusively controls the Ministry of Finance, all financial institutions, and money circulation. It controls as well the Ministries of Health and Agriculture. Both ministries have a huge vertical control of local appointments all over Serbia, including the big monopoly company „Srbija Sume („Serbia Forests) which is often described as a “state within a state“. The SRM-NS coalition has been allocated the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Capital Investments, as their most important ‘fiefs’. They have three more ministries: the Ministry for Diaspora, the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Commerce &Tourism. The NS (New Serbia) controls the Railways of Serbia, while the SRM controls Yugoslav Airway Transportation (JAT)[1].

The “confederation of feuds“ of the interior, economy and finance (where the power lies) is in fact an exchange system of services and interests between the parties in the coalition (and their hidden financiers) based on mutual blackmailing to withdraw MPs from the Parliament if a Minister (i.e. president of the Party) were to be denounced for corruption.[16] This system corrupts key state institutions: police, intelligence[17], judiciary, finance and economic institutions, health care and the national budget expenditure. It is not an exaggeration to say that the ‘feudalized government’ is integrated by its own corruption.

The Case of the Ministry of Finance

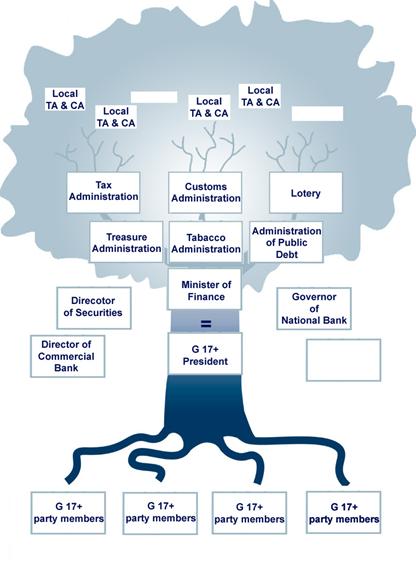

To demonstrate the very peculiar structure of the Government of Serbia, which I have described as a confederation of ’power fiefs’, I will analyze the Ministry of Finance and public financial institutions. G-17 Plus has been allocated all portfolios regarding finance; its leader is the Finance Minister (he is the active President of the G 17 +) and he has appointed “reliable“ associates and party cronies to the posts below him. The same party has been given rule over central financial institutions and services. Primary among them is the National Bank of Serbia although it should have independent status. The party also controls the Commercial Bank, the Securities Commission et al., the Tax Administration, the Customs Administration, the Lottery, the Money Laundering and etc. which are different departments of the Ministry and under its control (see Picture 2). About 90 per cent of all positions are appointed by party criteria and are members of the G 17 Plus. [18] (See Picture 2).

Picture 2: Tree of G17 Plus’ Fief

Statistics

of Serbia

The striking fact is that institutions, like the tax and customs administrations, the National Bank of Serbia[19], the Securities Commission, The State Statistics, and other institutions that have to be independent from political influence are interwoven with party functions[20]. The lack of transparency in the recruitment and function of these party/state fusions at the central level has severely damaged the accountability of the government.

Apart from the horizontal (at the national level) party rule, this party also rules vertically by appointing the heads of local tax administrations, customs boards and other local administration units. Procedures for local appointments include proposals from the local party units. In practice, employment opportunities for the heads of local tax administrations, customs, etc. are not publicly advertised or discussed officially; local party boards recruit the heads of the local administration units all over Serbia. The selected candidates are sent to the Minister for approval. About 90 percent of the director appointments at the local level for tax, or customs offices are from the ranks of the G17 Plus. In practice, horizontally and vertically, all the financial branches and the money circulation are under the control of one party without internal or external control, nor competition for the appointments. Two hierarchies – the party and the state have overlap. That is how the closed, ’feud’ system of authority functions.

The case of Ministry of Education and Sport (MES)

The next analysis showing the comparison between the first and second post-Milosevic governments related to the party membership of the Ministry itself, appointed Heads of the County Educational Departments and the appointments in institutions, companies and commissions dealing with education in Serbia, reveals the degree to which professionalization has been replaced by the party system in this Ministry:

Party Membership of the Ministry in the First and Second Governments:

|

Positions |

I Government |

II Government. |

|

Minister |

CAS |

DPS |

|

Vice-Minister |

DP |

DPS |

|

Deputy Minister |

Non- party |

DPS |

|

Deputy Minister |

Non- party |

DPS |

|

Deputy Minister |

Non- party |

DPS coalition party |

|

Deputy Minister |

CAS |

Unknown |

Composition of the Heads of County Educational Departments, by party affiliation:

|

Counties |

2000/ Minister/ CAS[21] Heads |

2004/ Minster/ DPS Heads |

|

Sombor |

Non-party |

DPS |

|

Zrenjanin |

-||- |

DPS |

|

Novi Sad |

-||- |

DPS |

|

Pozarevac |

CAS |

DPS |

|

Valjevo |

DP |

DPS |

|

Kragujevac |

Non-party |

DPS |

|

Nis |

CAS |

DPS |

|

Zajecar |

DC |

DPS |

|

Leskovac |

Non-party |

DPS |

|

Beograd |

CAS |

DPS |

|

Kosovo-Ranilug |

Previous |

DPS |

|

Kosovka Mitrovica |

-||- |

Previous |

|

Cacak |

- |

DPS |

|

Krusevac |

- |

DPS |

When the new government came into power, the Heads of County Educational Departments appointed in 2000 were all dismissed; the turnover at this middle rank position was one hundred per cent. All new appointments were exclusively selected from the dominant party for this party fief (the Minister’s Party is the Democratic party of Serbia - DPS). Since their professional reputations were much lower, this turnover meant that more-qualified people were replaced with less-professional directors. This change reflected the changes in the Ministry itself: the best experts available in Serbia were hired as leaders of the educational reform in the first government, but they were all thrown out to give place to the “reliable“ people of the new dominant party.

The same type of one-party control criteria can be found in all other educational institutions: The Centers as well as the semi-independent institutions (founded by the Ministry) devoted to development and evaluation of the quality of education, professional training of teachers, etc.) were reorganized. The directors of the centers ( experts and non-party people) were dismissed and replaced with less qualified people from the DPS.[22] Public companies founded by the Ministry such as the very profitable company for Text Books Publishing, were given to the DPS.

The same party (DPS) got the position of President of the Commission for Education in the Parliament. On the lower side of the hierarchy, going down to the directors of the schools, the official procedure theoretically empowers the schools boards composed of 9 people (3 parents, 3 school employees, and 3 from the local government) to elect the director and send the elected candidate to be approved by the Minister. But in practice it is not so, because the 3 people from the local government who are from the party, impose the selection of the school director in many cases.[23] . The forging of party criteria for appointing directors of the primary and secondary schools all over Serbia, has led to numerous public conflicts between the Minister and schools which did not want to accept the imposed and unqualified directors. Only when the schools threatened to go on strike because of the political appointments imposed by the Ministry, were they able to win the battle for more qualified and professional directors of the schools.

Upon investigating the individual appointments of directors at the local level, in schools, libraries, cultural centers and etc., and noting the number that were appointed by the central government, it was evident that non-party candidates have had almost no chance to get a director position in local-level institutions[24]. The analysis of some individual cases has shown that at the very moment when one party ”conquers“ a ministry, the local party functionaries start insisting to party headquarters that they get the leading position against other candidates in the competition. The party administration prepares the case for the Presidency of the Party to influence their ministers to appoint “our people“.

External competition for jobs, outside of the parties, is eliminated. By preventing competition, corruption becomes protected within the political/party hierarchy and is influenced from the top positions of the government. This is a general rule applied in all ministries, middle administration positions in the counties, institutions, companies - down to the local level offices.[25]

Public companies

Privatization in

Serbia is only half finished. In total, about 50 percent of the

companies are still owned by the state, or have mixed state, social and

private property. When taken together, 40 percent of the total

workforce lives in the unreformed economy.

The most important aspect of state capture is the ‘seizure’ of the public companies. Parties in the ruling coalition exclusively manage them. Public property has thereby effectively been converted to “party property” and is managed in its interests. And it is a huge amount of assets that has been captured. The 17 biggest companies founded by the government of Serbia are managed by the parties that comprise the ruling coalition at the National level: - the managing boards, presidents, and directors - are compiled and by a quota system are divided up among each of the parties of the ruling coalition which appoint the management positions as if the companies were their own property. All other companies – about 500 – are in the hands of the ruling coalitions on the local levels (see the quadrant[26], below).

There are many indicators that management hiring decisions in the public companies do not follow the criteria of merit, experience and qualifications. Nor are managers held responsible for results. If the government wants to keep low prices, producing losses, the managers appointed by the parties must comply. This is the case with electricity prices that are lower than in the rest of the region. Justification for controlling prices in electricity (or other prices) is socially based, subsidizing low salaries of the population. But the low prices have also provided substantial real benefits to the private interests of the party-related firms that are selling electricity abroad. Such discretional decisions about prices in public companies can bring enormous profit to the tycoons who are financing the parties of the ruling coalition.

Additional benefits for the party include the companies being used for the employment of party members and for rewarding party functionaries for their loyalty with the extra incomes of directorships, Parties may also get free direct services such as publicity for their campaigns, the publishing of journals and advertising materials, the delivering of presents to the socially deprived in the name of the party, etc.

The ‘right’ to appoint directors, as well as managing boards, is not subject to any public control regarding the use of resources, salaries for the management board, and the external auditing of the real situation in the company. When asked about the salaries of the top management, the directors of the public companies chose not to answer, saying that it is a “secret”.[27] Detailed research on salaries in public companies shows that the average income of the employees is not significantly higher that in other enterprise. Income is much higher only for the top-management boards who, in individual cases, receive more than 500.000 dinars per month (6 thousands euros, in a country where the average salary is 200 -250 euros). Incomes for the members of the managing boards vary from company to company but they can be two or three times the average managerial salary. The true benefit is even much greater because it is not a job, but a position that can be held in addition to regular jobs or other positions.

Party-nominated management boards are not there to control and supervise the business results of the company and work for the public interest, but to “close the eyes” for their own and the party interests. Public companies are the nest of corruption and the loss of public money. This can be changed only by the process of privatization. The IMF suggests that the real reforms will start when public companies, (most often monopolies) enter an adequately designed and controlled privatization process. Only then will the real reforms in Serbia take place.

Local level: The Case of the City of Novi Sad

The city of Novi Sad was selected as a case study to demonstrate the link between party gains and the turnover of executive, public companies, utilities and services. This city is a clear case of the party shift after local elections because the Serbian Radical Party (SPR) won the last elections in 2004 (with two coalition partners: the Socialist Party of Serbia and the DPS) after the Democratic Party (DP) had dominated the city for 8 years. The Radicals got 35 elected members of the City Assembly, and with their partners, had a majority of 42 representatives (out of 78 assembly members). Before the last elections the majority was held by the Democratic Party and its coalition partners.

As has been demonstrated

for the national level, state capture of all positions in public

offices is the model operating at the local level as well. On the local

level it is more visible how elected people get jobs in public

companies, and how nepotism operates together with

cronyism.

The Structure of the City Authority

|

Government/Secretariats

|

City Council 2004-* |

City Council 2000-2004 |

|

Mayor (directly elected) |

SRP |

LSV[28] |

|

City Architect/Urbanism |

Quota of SRP |

LSV |

|

City manager |

SRP |

- |

|

Budget and finances |

SRP |

DP |

|

Communal activities |

SRP |

DP |

|

Transpiration |

SRP |

LSV |

|

Social protection |

SRP |

CAS |

|

Sport |

SRP |

DS |

|

Environment |

SRP |

- |

|

Culture |

SRP |

LSV |

|

Education |

SPS |

Reform Party/Vojvodina |

|

Economy |

SPS |

RP/Vojvodina |

|

Administration and legal affairs |

SPS |

DS |

|

Health |

DPS |

CAS |

|

Information |

- |

Social democratic party (SDP) |

The table shows the government structure by the party-related distribution of the “ministries” and positions in the local government. It shows that there was a 100 percent turnover after the local elections: one party (coalition) enters the local government and occupies all public positions; after the next election, another army comes to take their positions. It also demonstrates that no professionalism is needed. As soon as one group of people gets the knowledge and experience to lead health or education etc. it may be thrown out and replaced after the next elections. Over 1000 people who were appointed by the Democratic Party before the last elections had to find another job, and it will be the same with Radicals when they lose the elections and a new coalition comes into power in Novi Sad. All the money which had been invested in the training of local government cadres was wasted because there is no professionalism in the local institutions. Since local government and services are closest to the needs of the citizens, such practice of total politicizing of local functions is damaging to public interests, as if local governments exist only to employ party cronies, families and friends.

The “turnover” of power is used in several different ways for the benefit of the party cronies, families and friends against the citizens and the public interest:

1) To get leading positions in the public companies. Of the 42 members of the Assembly who were elected, 24 got jobs in public companies in the positions of directors and professional posts. Three members of the City Assembly elected from the DP list, left their party and joined the Radicals majority for family reasons (to protect their husbands from losing director positions which they had in the previous distribution of the managing position in the public companies).

2) More than 1000 people got jobs without public advertisement and competition in the city administration and public companies. During the first 13 months of the rule of the Radicals, 965 people from their party were employed in the public companies and utilities (while the DP employed 654 people during the 8 years of their rule). Many of the employments were based on nepotism (family and friendship ties), creating numerous scandals in public. The mayor of Novi Sad reacted to nepotism scandals by delivering a special announcement “that she is against nepotism and conflict of interests, calling appointees to show public awareness and give up positions obtained in such an immoral way”. But nothing has changed. All the “immoral positions” have remained in the hands of family members, party cronies and friends.

3) More than 30 people without the required educational qualifications, via family and party ties, got jobs in the city administration, in leading positions in the public companies and utilities (there are 15 such companies under the rule of the city and they are in the hands of the ruling coalition) and in institutions of culture, urbanism, museums, school boards and directors and etc.

4) The Radicals have ignored the previous practice that the presidents of the managing boards of the public companies (and institutions) and the presidents of the monitoring boards must be from different parties. This practice had enabled some elementary internal control to be established. Now both the president of the managing boards and the presidents of the monitoring bodies are from the same party.

5) The dramatic lowering of the qualifications of the appointees in the local government and companies, has led to huge losses which must be covered by the city budget (which is created from the money of the citizen tax payers). The financial reports of the city companies have shown that they have been making less and less profit; the city transportation company has had a five-times bigger loss (deficit) that it had in 2004 (when the Radicals came to power) while the biggest company (The Sport Center of Novi Sad – SPENS) has suffered losses for the first time in its history. The City Assembly passed a revision of the budget by which an additional 750 million dinars in subsidies was approved for the city companies. This means that more than half of the city budget is being used to subsidize public companies.

6) The salaries of the directors in the public companies have been raised to such an extent, that 44 of the directors of the public companies and institutions (as well as their advisors and deputies), were on the list of millionaires of Novi Sad. The Director of the Public Transport Company which has had the biggest deficit has the biggest salary; the second on this list is the Director of the Institute for Building Novi Sad, the third is the Director of the Business Premises Areas, and so on. All directors with the highest salaries are high functionaries of the SRP and some of them are also members of the National Parliament.

In conclusion, data for the City of Novi has demonstrated that the “capture state” and its feudal mechanisms installed by the ruling parties, has operated on a local level in an even more visible and arrogant way; it has severely corrupted the public sector at the expense of the citizens and their public interest.

III. Degradation of the Serbian Parliament and Multiple functions of MPs[29]

Serbia has a proportional election system: the whole country is one electoral unit, and each competing party offers its list of candidates for the 250 seats in the Parliament. This electoral system usually produces coalition governments because no single party can gain a majority. The Parties’ presidents have been able to take control over the seats in the Parliament first by composing the candidates’ lists and then by deciding which candidates will enter the Parliament after the elections, irregardless of their order on the list. The arbitrary selection of who will enter the parliament is a relevant corruptive mechanism of state capture permitted by the electoral law. Moreover, those who are selected to enter the Parliament are obliged to sign blank resignations prior to entering the Parliament. This has become an illegal ‘invention’ of the parties. These blank resignations are kept by the party leaders, who activate them as needed. If an MP is disloyal or does not vote as instructed (this is especially so for the MPs of the ruling parties), s/he is stripped of his or her mandate and thrown out of the Parliament. This is done despite the decision of the Constitutional Court that the mandate belongs to the individual MP (according to the letter of the Constitution) and not to the party. Although the activation of the blank resignation became evidently illegal, it is still being used to throw out disloyal MPs when they don’t want to vote for some laws [30], or when their vote threatens the parliamentary majority made up of several parties which elects the government. The loss of a majority in the Parliament leads to the fall of the government.

To help eliminate the corruptive mechanisms from the Serbian Parliament, the Venetian Commission on Serbian Electoral Legislation has suggested that the electoral legislation in Serbia has to be changed to make clear that (a) mandates belong to the individual MPs, (b) parties and coalitions must announce in advance the numerical order of the candidates who will enter the parliament from the lists, and not to be allowed to choose after the elections which candidates will get the mandate. Under current practice, citizens never know who they are voting for. But instead of enacting the suggested reforms of the Electoral Legislation, the new Constitution, created by the agreement of the four leaders of the parties, clearly states that the mandates belong to the parties. The ratification of the new Constitution will make it more difficult to eliminate corruptive mechanisms from the parliament.

To cement their obedience, MPs are corrupted by being given money for trips they never made and parliament committee sessions they never attended. But the main bribery mechanism lies in the opportunity of the MPs to accumulate offices: MPs can simultaneously be mayors of cities (or municipalities), presidents of the regional government or the members of the local governments and be on managing boards of funds or agencies; they can be elected assembly members on all other local levels (city and the province).They can be business advisers, city land bureau directors, members of the managing boards, presidents or directors of public companies. The only limitation for MPs imposed by the Law on the Conflict of Interests (passed in April 2004) is not to have a managerial position in more than one public company at a time. By the same law, MPs explicitly have the right “to keep their managing rights in other business enterprises, if that does not influence their public functioning and their impartial and independent performance”.

Holding multi functions allows MPs to have several sources of income (see Chart 1). It is shown in Chart 1 that 61% of MPs have other functions, of which 44% have one more function and 17% hold two or more functions. Getting the most lucrative functions in the public company is possible only by decision of the president of the party. This gives the party presidents great power by allowing them to deliver ‘rewards’ to other party functionaries. The richer the public company one gets, the more he/she will gain by sitting on the managing board.

Total MPs=246

Chart 1: MPs

multi-functions

|

Chart 2: MPs multi functions by content

I have identified 23 individual MPs who are concentrated in 4 public functions. When some of the party leaders were interviewed about the reasons for the accumulation of functions, the answer was that the mayors of the cities and municipalities, and the directors of city land bureaus and other institutions want to be MPs for the immunity they would enjoy. Being liberated from the restrictions of the Law on the Conflict of Interests (which is tightly controlled by their parties), and enjoying a widely-defined immunity, the MPs can provide ‘state capture ’ in a literal sense as the ‘seizure’ of laws to the advantage of corporate business via influential political links in the Parliament. They have the privilege to be “legally bribed”.

Regulations on conflict of interests serve to set standards for public office performance, build citizen confidence in state institutions, and prevent multiple functions and corruption. In essence, these regulations put limits on the accumulation of functions by public officials, which always leads to the concentration of power in a society and the degradation of public interest. If public officials are acting in many public roles, they can not comply with the requirements of so many roles, thus damaging public interest. The Law on Conflict of Interests passed in Serbia has not met public expectations for the following main reasons:

1) Many public functions were not embraced by this law, including roles exposed to corruption, such as positions in the police, customs, tax administration, intelligence and security organs, jails and many other important functions;.

2) The law allows the accumulation of functions;

3) The Republican Commission for Preventing the Conflict of Interests - is not professionalized. It does not set criteria for the election of its members (even education requirements do not exist) and their competences are not defined. Members of the Commission have other jobs in the private and public sectors and they make decisions ad hoc. How they are elected is also questionable ( the Supreme Court elects 3 members, the Bar Association 1 and the National Parliament 5 on the proposal of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Art);

4) The Law does not contain sanctions for the conflict of interest. It can only give non-public warnings followed by public recommendations for resignation if the non-public warning does not have an effect on violators of the law. The property of the functionaries is a secret not available to the public etc.

IV. Regulatory Institutions, Laws and Anticorruption Policies in Serbia: An Overview with Special Attention Given to the Law on Financing Political Parties

From the point of the ’state capture’ problem, we will see what Serbia has been doing to create independent regulatory institutions, and anticorruption policies. We will investigate how far it has proceeded towards controlling the political governing process and the powerful “political class“, and towards reforming the economic process so as to reduce and eliminate monopolies and the special privileges of the business elite (tycoons) based on political influence.

If Serbia wants to join the EU integration process, she must build strong anticorruption institutions whose target must be to improve the performance of the public sector in general, rather than to reduce corruption per se. She must improve the meritocratic orientation of the civil service as an important step in the long-term process of reducing corruption; she must establish the supreme independent auditing institutions to control budget expenditure audit how taxpayer money is spent (this institution should control all public budgets, including the Serbian National Bank and the managing of public money, public companies, political parties etc). She must establish Ombudsman and anticorruption commissions and agencies and build a wide network of regulatory institutions and monitoring boards which can strengthen the capacity of the society to prevent the excessive influence of state organs and political voluntarism. Effective legislative improvements are also needed such as a law on the free access to information, an improved law on conflict of interests (which I have previously commented on), a law promoting free competition, a law on the financing of political parties, regulations of the One Stop Shop concept, and so on.

Serbia has started to form the above institutions but its policies have not been decisive, and the results are more than modest. The supposed regulatory institutions that have been formed (for example, the Regulatory Radio-Broadcasting Agency) all have grave deficiencies due to distorted political influence. Anticorruption actions have been arbitrary and abrupt, using selective arrests[31] and phony publicity; they have been ad hoc, being formed and disbanded from one day to the other. An example is the recent sudden proposal of the government (October 20, 2006) to form an Anticorruption Unit which would start work on October 1, 2007. Among the responsibilities of this Agency will be the control of the financing of the political parties.

We will now give a brief overview of some of the anticorruption institutions and laws, giving special attention to the Law on the Financing of Political Parties because of its key role in curbing state capture and the links between political party leadership and the economic elite (tycoons).

1) Almost nothing has been done to introduce meritocratic requirements for appointed positions, has not been done almost anything. The Law on State Administration has been applied since in July 2006. The problem is that there is no monitoring of its implementation, nor are visible advertisements required for employment opportunities in the ministries. It seems that the Law was used by the ruling parties to allow them to permanently appoint their party members so that they can not be removed. The Law did not cover public servants in the police, the customs, security, tax administration etc. Experts say that there is no “political will“ in our politicians to give up party influence. Such a change can only happen if Serbia advances towards EU integration and applies the policies and procedures that are required for membership.

2) In 2005, Serbia passed the Law on the Institution for State Revision, but it has not yet been formed; this Institution will now be incorporated in the new Constitution (after it is passed), so it may be formed in the not-too-distant future.

3) The Ombudsman Law was passed but no one has yet been appointed to that position. In Vojvodina an “advocate for the citizens“ exists, and a similar position was recently created in the city of Belgrade, but on the national level the situation has remained stagnant from the beginning. The Ombudsman will also become a Constitutional category, so that may help it to function properly in the future.

4) Anticorruption agencies and commissions have not yet been formed although the National anticorruption strategy was passed in the Parliament in December, 2005. What still exists is the Anticorruption Council, which was formed during the first transitional government, and which will be dismissed since the new Agency just mentioned will take its place. There are a couple of NGO organizations that are dealing with corruption. The most prominent and active is Transparency Serbia;

5) Regulatory institutions are being developed in Serbia but they are not independent from the executive or from political, and business influence. Their lack of independence has destroyed their reputations from the outset. Each institution has the same problem: they are purposely designed by law not to function. The examples of competition policy and the ’antimonopoly commission’ are typical.

Because of the huge domination of monopolies in Serbia (Serbia has received the lowest grade – 1 for competition policy),[32] it has been said that Serbia does not have any competition policy. Most of the public companies are monopolies; private firms as well look for privileges in order to avoid market competition (most commonly, protection is purchased by buying laws via connections in the Government). To curb monopolies, the Law on the Protection of Competition was passed last year. The “Antimonopoly Commission” was established after a long delay. The law will not be effective because of its evident deficiencies: it does not punish domination of a market, but only the “misuse of such a position“ on the basis of “reasonable discretional estimation“.

6) The latest draft law on foreign investments included the concept of One Stop Shop and it is another example of grave distortion of a good idea. The World Bank gave very serious remarks on how the law will open wide the door to corruption because of its deficiencies. In the law, the One Stop Shop will be virtual; it will not be an actual office. Each municipality (there are almost 200 in all) will be a One Stop Shop. The actual shop will simply be the discretional judgment of the mayor, and, for larger investment – the Minister of Economy. The One Stop Shop can be at the service of an investor, or he can be deprived of it, depending on the discretional decision of the mayor or the Minister, independently of what the law says.

The Law on Financing of Political Parties

The Law was passed in 2003 but it did not meet the expectations to prevent secret, under the table, party financing, which has become a tradition in Serbia, since the introduction of the multi party system in Serbia in 1990. The government and the parties are supported by big capital contributions and it is a well-known public ‘secret’ that the tycoons finance all the major parties. Individual donations are now officially limited to 100 dollars as a maximum, but they can remain anonymous and there is no control mechanism to assure compliance. In practice, huge amounts are being given.

What is needed is a transparent model for financing the parties and an efficient control mechanism. Serbia should pass such a law; there are many good practices that can easily be adopted and implemented. But the ‘financing law’ will be useful only if Serbia passes a law on political- party organization which is currently lacking. The law presently in effect is the old socialist law about ‘social-political organization’. This law is urgent because there are more than 400 parties in Serbia, so any serous control must start with what is a political party and what should be the procedures for its creation and activities.

The main problem of the existing Law is that it does not provide for the establishment of a separate institution to monitor the funding of parties and a separate body charged with supervision. The only control body of party finances is the Parliament Finance Committee, composed of the party members who are submitting the financial report. This means that the parties control themselves. This practically renders the law inapplicable.[33] The law suffers from numerous other deficiencies, as for example, limiting private donations to 20 percent of the money obtained from the budget (and only 5 percent for the city elections) for the election campaigns. The permitted amounts are so small that no campaign is possible from that money. The only feasible solution is to get money under the table. Because of the ‘holes’ and uncertainties in the Law, there is no discipline from the parties to submit financial reports officially or to present reports in the public.

Not only did the Law fail to make the operations of the parties transparent (it may have rendered them even less transparent); it also enables parties to draw between 5 and 7 million Euros a year from the state budget. There are many indications that politicians have systematically been creating loops of companies through which they have acquired a lot of that money.[34] Under the same political influence the supposedly independent, regulatory institutions (commercial courts, enterprise registries, the stock market and the media) compromise their ability to control corruption.

The sudden decision of the government to form a new agency which will take control of party financing only after the next elections, while the coming elections will be carried out under the unusable existing laws, only confirms that Serbian anticorruption policies are weak and as such, contribute to state capture and corruption.

V. Survey on public opinion on corruption and state capture

I have analyzed objective data on state capture as a ’framework’ for large scale corruption. But for anticorruption policies it is essential to know what the citizens, as the principle stakeholders, think about mechanisms of state capture, how much they trust state institutions, how they judge “party“ job allocation in the public sector, what they think of the multi functions held by the politicians and how to fight corruption. I have divided the survey data on the public opinion of the citizens of Serbia into three sections: (1) concerns of the public about corruption and public confidence in the main state institutions and party leaderships; (2) judgment about the existing criteria for job allocation for the leading positions in public offices and what the criteria should be, including the approval/disapproval on holding multi functions by the politicians; (3) tolerance to and awareness about corruption in public offices, and what citizens think should be the most efficient strategy to fight corruption in Serbia.

Concerns about corruption and confidence in institutions

The citizens of Serbia think that corruption is one of the four most important problems of the country. When citizens were asked to spontaneously choose the main problems Serbia is facing, the responses were the following: unemployment (55 %), low standard of living ((37 %), Kosovo (23 %) and corruption (28 %).[35] High awareness about corruption has a direct impact on their the trust of the main state institutions. Mistrust in the institutions and the perception of them as being almost totally alienated from the interests of the citizens is alarming. Their answers to the question “which public institutions“ work for the interest of citizens and for the general public good, show extremely low confidence in the institutions: only 6% of the citizens think that political leaderships work for the public good; Parliament gets only 8 percent positive votes, ministers - 9%, government 11% , courts 12 %, local governments 15 %, public companies 20 % and so on. All the institutions have dramatically more negative trust vote than positive (see Chart 3, Annex II).

For whose interests are these institutions and organizations working? Using a scale from 1- 5, for each selected state office, the results are extremely worrying. A great majority of the people, 71 percent, think that state offices work in their own interests, 70 percent say that they work for their parties, 69 percent say they work for their relatives and friends, and the same amount think that they work for „powerful people and businessmen“. Only 13 percent said that state offices work in the interests of the citizens!

In response to direct questions about the public organization or office in which corruption is the most widespread (using a scale of 1-5 for each institution), 77 percent think that the political parties are the most corrupted, tied for second in line with 75 percent were doctors and MPs, and so on (see Chart 4, Annex II).

Job appointments for public offices

Citizens have a realistic perception about how positions in public offices are filled, confirming my research data. When asked about how appointments should be made, the response was almost totally opposite to the practice in reality. The citizens indicated that merit-based appointments should be the most important criteria used. More than 90% said that it should be the first criteria taken into account ( Chart 6). A dramatically different picture was given about how they view the practice to be in reality. Citizen responses estimated that party membership and family/ friendship ties are the most used criteria (77 % and 76 %, Chart 5), while merit and qualifications play a much lesser role in the selection process.

Perceptions about the procedures for recruiting for jobs in public offices, show that 49 percent of the citizens think that advertisement for public office positions do not exist, and that parties, independently allocate these positions to their own people within the party coalition agreements. 40 percent think that when positions are advertised, the competition is fixed in advance. Only 8 percent of the interviewed citizens think that public advertisements of positions and the opportunity to apply are accessible to everyone.

The general public perceives the holding of multiple functions by politicians to be a negative practice and a problem. Over 90 percent of the total sample of citizens had this point of view. Among responses regarding multiple functions, 27% said that this phenomenon was caused by greed for money (to have many sources for income); 24 % said that it is a problem because it is not possible to exercise so many functions and to perform them properly and in the interest of citizens; 20 percent estimated that multiple functions mean a concentration of power in a fewer hands and that it is not democratic; 19 percent estimated that multiple functions give too much power to the parties. Only 9 percent said that having multiple functions is not a problem if someone is sufficiently capable to fulfill them all in a proper way.

Citizens as well

disapprove of the practice that highly-positioned statesmen/women are

playing active, high-level roles in their respective

parties. Fifty-four percent of the sample disapproved of the

practice, 29 expressed their disapproval only for the highest positions

(Prime Minster, President of Serbia and ministers) and 15 percent think

that having both an active party function and a state duty or duties

does not influence the effectiveness of their performances of both

roles.

Tolerance to corruption in public offices and the efficient anticorruption strategy

The citizens of Serbia are very sensitive and intolerant to corruption. They said that if they knew that a politician from the party s/he usually votes for was corrupted, s/he would go to the party to denounce him (34 percent of the answers), 33 percent would not vote (would abstain), 22 percent would for some other party and 4 percent said that in spite of the corruption they would vote for their parties because the others are not any better.

Other indicators on the same issue once again demonstrated a high sensitivity and intolerance for corruption. Citizens claimed that they would immediately denounce someone who would ask for a bribe, but my opinion is that this is an overestimated expression of action that would not really be carried out when faced with bribery. In response to a question about the relative corruption of political bodies (saying that political corruption is the same in developed countries but did not prevent them from developing), 45 percent strongly disagreed with such a statement, while only 13 percent agreed (the others did not express an opinion).

Concerning why corruption is not being eradicated, 46% of the respondents expressed the view that the state is doing little to curb corruption because corruption is located in the state organs, while 21% felt that the institutions such as courts, inspections, budget controlling mechanism are not working and a lesser number that said that their was no money to fight corruption, that political parties are not giving enough support and citizens are not supportive.

What do citizens think would be the most efficient policy to fight corruption? They gave three main and mostly supported answers. First, special and independent bodies must be created to fight corruption as the only focus; second, the rule of law and independent courts must be strengthened. and third, internal and external controls must be established for all public institutions together with sanctions for those who violate the rules and standards in the public sector. A small amount, about 5 percent each, mentioned the need to increase the involvement of all citizens, the need to prohibit multiple functions, the need to introduce obligatory standards of behavior for all the public servants, and the need to develop investigative journalism.

Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

The complex transition process in Serbia remains overloaded with the

specific problems of the past decades; it has not yet been liberated

from its heavy inheritance. It is evident that Serbia is again

refocusing on the ’national question’ which has been the

ideological and old-style manipulation used by the “political

class” in the past. Because of this “step back” into

the past, the present Serbian government (specifically its

leading party in the ruling coalition) has not complied with

Serbia’s international obligations to extradite Ratko Mladic and other

accused Serbs to the ICTY for war crimes. This has held up the

negotiations with the EU about the S&A agreement with Serbia.

Internally, in conjunction with the distancing from and loss of

ambition to integrate with the European Union, there has been a lack of

“political will” to continue with political reforms,

institution building of the in the judiciary system, good

governance, and more-transparent and accountable executive

organs. This has enabled the political/ state elite to capture

the state and all public institutions and to use them for their

interests, delaying the establishment of the controls, regulatory

institutions and laws which could hold the political elite

in check. The unrestrained political leadership in Serbia has

demonstrated a strong tendency to collude with and sustain the

monopolies and privileges of private businesses. As a result, the

supposed plural, multi-party regime has been converted into a rigid,

party-feudal, governance over public institutions and citizen

interests. This conversion was identified as the phenomenon of state

capture, which works on a two-way track: it seizes state

influence and all public institutions for its own interests, and

trades them for the illegitimate needs of privileged business (tycoons)

in return for secret financing . We see state capture as a specific

governing process as the main framework of the large scale and systemic

corruption in Serbia.

With such corruption, policies must be orientated towards imposing strong legal limits and control on the unrestrained political and economic elites and their powers. In other words, the policy has to affirmatively create good governance institutions and supportive legal environment rather than to focus entirely on the negative consequences of the system’s illness.

In the context of Serbia’s, road to the EU integration processes and the state policies necessary to curb state capture and its consequential systemic corruption, we see that three main policy steps, or the three main levels of policy recommendations, should be made.

The first policy level refers to the EU and international support for Serbia to overcome its political and transitional crisis. State capture, oligarchic social structure and systemic corruption are clear indicators of the unsatisfactory transition and long-lasting political crisis of the state building policies and complying to her international obligations related to the cooperation with ICTY and coming to terms of her immediate past.

To break through the political stalemate of Serbia’s international obligations, the following EU policies are recommended:

1. Support the pro-European democratic forces and the civil sector, aiming at marginalizing the old nationalistic forces, which are the anchor of the state capture system and anti-European values and institutions;

2. Urgently demand that the new Serbian Government, which will be formed after the upcoming elections, extradite Ratko Mladic and other accused Serbs to the ICTY, (December 2006 or the beginning of 2007) in order to continue the negotiation process with the EU. The fulfillment of the obligation to the ITCY gives enormous potential to Serbia to eradicate the secretive state bodies of the old regime in the police and military, which are the true stakeholders of state capture, nationalistic manipulation and anti-European policies;

3. Strongly support Serbia’s EU integration process, irrespectively of the present ambivalence about the future EU enlargement. The integrative process in itself, with its insistence on political and economic reforms, free trade, and institution building, is more important than the final goal of becoming a full member of the EU, although the goal has to remain tangible because of its motivational effects for sustainable reforms and changes.

The second level

polices

are derived from the analysis of state capture mechanisms that

state policies can eradicate by:

4. Establishing without delay controls in all areas of the public and private sectors where they are missing. This includes the implementation of the already existing law on the State Revision Institution for all public budgets);

5. Improving the already existing laws and their regulatory bodies so that they may be more effective in their control of executive/ political influences and may prevent their collusion with private business; in particular, the new model law on financing political parties should be prepared and submitted to the Parliament and an effective control body should be set up for its implementation;

6. Advocating improvements in the Law on the Conflict of Interests which was passed with many defects. It must cover all functionaries, it must prohibit multiple public functions for the MPs and other government officials and it has to professionalize the Committee for the Prevention of the Conflict of Interests;

7. Improving competition policy and eliminating monopolies and privileges in the Serbian economy by introducing more effective “anti monopoly” bodies, privatization procedures and free trade policies and agreements;

8. Setting up new regulatory institutions on the national and local levels such as Commissariats whose role would be to establish competitive criteria for all appointments in order to promote meritocratic standards instead of present party cronyism and nepotism;

The third level policies emanate from the survey

data we have presented. They refer to the building up of civil

society’s capacities and NGOs alliances to open up public debates

about state capture and its corruptive mechanisms, to campaign

against the “feudal division” of the executive power in the new

governments that will be formed after the elections and to

initiate dialogues with the more open-minded political parties about

changes in election laws. The aim of the activities should be to

strengthen the responsibility and professionalization of the MPs, and

to advocate giving up the mingling of state and party functions at the

highest levels. Our research and survey data will be presented to the

top politicians to convince them to take into account public

opinion about the almost total distrust of the political institutions

and political leaderships that is leading to an alarming

alienation of the citizens from the political leadership and

institutions. The systematic and sustainable external influence of the

civic organizations and NGOs can bring about the changes that are

needed in the leadership style in Serbia.

[1] The beginning of the transition in Serbia counts from the fall of the regime of Slobodan Miloseivc, October 2000.

[2] Anticorruption in Transition 3, Who is Succeeding…and Why? Authors: James H. Anderson& Cheryl W. Gray, WB, 2006

[3] In the Serbian Public , assassination of Zoran Djindjic was understood as resistance of old cadres in security institutions to his intention to modernizes Serbia and to prepare the country to join EU as soon as possible. His cooperation with the Hague Tribunal for crimes was the threat to military and secret polices to be reformed and brought in new people.

[4] It is Democratic Party of Serbia (DPS) whose president is Vojislav Kostunica, presently Prime Minister of Serbia, and ex- president of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

[5] This proves the fact that EU has stopped negotiations with Serbia about S&A agreement because of the lack of political will to extradite Ratko Mladic to a and other accused for war crimes to ICTY.

[6] Law on Prevention of Conflict of interests was passed in April 2004; Law on Free Access to Information, November 2004, Law on State Revision Institution, at the end of 2005; Law on Protection Competition, “anti-monopoly law,” September 2005.

[7] Research into the origin of the present-day economic elite indicates it was recruited from socialist companies since 1989; their former directors, experts and managers, once part of nomenclature, are the ‘tycoons’ of today. Mladen Lazic, “Recruitment of the New Economic and Political Elites”, Republika,, June 2006.

[8] The whole case, in detailed, was presented and published by the Council Against Corruption of the Government of the Republic of Serbia, in Serbian and English: Corruption, Power, State, Part two, prepared by Verica Barac and Ivan Zlatic, Republika, 2005.

[9] For descriptions of the corruption affairs, see Occupation in 26 Months , 2004-2006. Center for Modern Politics (Centar za Modernu politiku), Beograd 2006.

[10] These four parties are: : Democratic Party of Serbia (DPS) of Vojislav Kostunica, Democratic Party ( DP) of Boris Tadic and President of Serbia, Serbian Radicale Party (SRP) of Vojislav Seselj as the biggest inidividual party in the Parliament, and G 17 plus of Mladjan Dinkic, presently Minister of Finance.

[11] The official justification for such hasty adoption of the new Constitution was to “preserve Kosovo in Serbia” by saying in the Constitution that Kosovo is part of Serbia.

[12] Given the current constellation of political forces and the proportional election system, no party can win a majority, wherefore coalitions are formed at all levels of authority. At the local government level, coalitions are broader and their clashes over the division of power are the cause of constant decompositions of the local governments.

[13] For instance, the Capital Investments Minister publicly admitted he had not respected the procurement procedure when he was buying Swedish railway cars; he has, however, suffered no consequences because his dismissal would have prompted the withdrawal of his MPs' support to the Government and the Government would have fallen. The Finance Minister found himself in the same situation, but the same mechanism of total irresponsibility was applied, justified by the need to 'preserve the majority'.

[14] The DPS (Democratic Party of Serbia), president Vojislav Kostunica and Prime minister of Serbia; G 17 Plus, president Mladjan Dinkic, Minister of Finance; SRM (Serbian Renewal Movement of Vuk Draskvic, President of the Party and Minister of Foreign Affairs, and NS (New Serbia), President Velimir Ilic, Minister of Capital Investments. The government thus composed, still did not have a majority in the Parliament, and as a minority government, it is supported by the SPS (Socialist Party of Serbia of Slobodan Milosevic, presently led by Ivica Dacic).

[15] The first post-Milošević government was formed by 18 parties, but had avoided the 'feudal' division of portfolios. The first government (2001-2003) had two parts: one composed of experts and non-party parsonalities who got the position on merit and, the second part was political, composed of numerious political leaders of the parties who participated in the grand coalition against the Milosevice regime and who got the positions of vice-prime minister. The composition of each ministry was a mixture of different parties, so that control could be achieved even without strong and strict instittutional rules of control.

[16] When the Direction for Public Procurement went to the public that the Minister of Capital Investments did not respect the procedure for buying railway cars, and the Minister admitted in public that it was true, nobody from the Government, including the Minister of Finance and the Prime Minister reacted. It was more important to protect the “party college” than the state and public budget. Danas, 27 October, 2005.

[17] The Intelligence was used last year to spy on the MPs about their intentions to vote for the Budget of 2006. Two people were expelled from the Parliament overnight because they said that they would not vote for the Budget.

[18] Data about both ministries and their party appointments have been optained with the help of journalists and insiders in previous and present high senior positions in the Ministries.

[19] Since October 2000, Serbia has changed three governors of the National Bank. The first Governor was Mr. Dinkic, at present Minister of Finance; the second was a non-party expert appointed to replace Mr. Dinkic because he, as a vice-president of the G 17, was involved in partisan politics; the third governor of the NBS was a candidate from the ranks of the G 17 Plus, when this party became the member of the ruling coalition.

[20] For example the Director of the Tax Administration of Serbia was a member of G 17 Plus; advancing politically, he became the member of the G 17 Plus Executive Board; recently he was transferred to the position of State Secretary in the Ministry of Finance, while his position in the Tax Administration was given to another prominent member of the same party.

[21] Two Parties in the first government - Civic Alliance of Serbia (CAS) and Democratic Center (DC) are small liberal parties with many professionals and experts, and both jointed the big coalition against Milosevic.

[22] One MP in the Parliament said that we can “speak about the terror of government and politics over professionalism and qualifications in the state administration”.

[23] One candidate for the school director in the city of Nis was threatened with death if she did not withdraw her candidacy. She was a victim of political revenge, as was the case all over Serbia. It was said that in all institutions and procedures, political pressures are taking place.

[24] The case refers to the selection of the heads of libraries which the Republic of Serbia has founded and whose appointments are given to the Ministry of Culture. The head of the libraries in the cities of Nis and Jagodina have been appointed according to the party criteria of the Minister, which initiated polemics in public. Candidates with more qualifications for the job threatened that they would appeal to the International Labor Organization for protection under the equal access to jobs and functions. Via personal contact I learned that in many cases ministers are informed who the favorite in the competition should be by local party boards.

[25] The Police Minster has replaced all 16 Heads of Police Districts, and in total, he replaced about 700 senior policemen since he took over the office. There is no audit or supervision of budget spending in the Police, nor civilian control of the police and intelligence. Police procurements are a „state secret“ exempt from monitoring.

[27] Although the Commissar for the Free Access to Information reacted, and asked the companies to give the answer under the obligation of the law, there was no answer.

[28] League of Social-Democrats of Vojvodina.