policy

making and strategic environmental assessment

at HUngarian local governments

Final Research Paper (April 2004)

Gábor Szarvas

International Policy Fellow, Center for Policy Studies (affiliated

with the Central European University and Open Society Institue) Budapest,

Hungary

1 Introduction

Managing local environment has always been a key aspect of local policies even before environmental problems gained large scale attention in the 1980s. It has, however, not been long ago that environmental decision support and management tools, such as impact assessments, environmental planning, programming, and management systems started to play more significant role in local policies. Long term planning and the implementation of systematic tools have been strongly supported by the development of the sustainability agenda.

Strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is commonly defined as the application of environmental assessment to policies, plans and programs. More specifically, it is “a systematic, on-going process for evaluating at the earliest appropriate stage of publicly accountable decision making, the environmental quality, and consequences of alternative visions and development intentions incorporated in policy, planning, or programme initiatives, ensuring full integration of relevant biophysical, economic, social and political consideration” (Partidario, 1999).

The concept of SEA builds upon the idea and practice of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), which since its introduction in the 1970s has been applied worldwide as a tool to support decision-making on environmentally significant projects. The application of SEAs has been promoted by international initiatives, such as the UNECE negotiations on an International SEA Protocol, as well as the EU Directive 46/2001 “On Environmental Assessment of Certain Plans and Programs”.

Current international SEA practices tend to be based on modified EIA procedures and methods, and involve a linear process of identification, prediction and evaluation of environmental impacts (Sheate et al., 2001). However, this approach has been criticised for its assuming of a straight-forward, rational decision-making process, which is often not the case in actual policy-making. (see e.g. Nilsson and Dalkman, 2001). It has been pointed out that the links between environmental assessment and the decision-making process are crucial to the effectiveness of SEA (Therivel and Partidario, 1996).

Alternative approach to SEA therefore suggests that strategic environmental assessment should fit policy making in order to be effective for, as well as successfully adopted by policy-makers (Nitz and Brown, 2001). Advocates of this approach, therefore, emphasise the fundamental need for understanding the policy making process and establishing the opportunities and means for SEA to contribute to it.

As a result of the international initiatives, and more importantly of the eastern enlargement of the European Union, SEA is expected to become more and more applied in Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, as well. The success of SEA application is, however, dependent upon the way it is applied, which in turn depends upon the preparedness of these countries and their policy-makers and practitioners for a meaningful adaptation of the method. An important element of the preparation is conducting well-founded and relevant studies on policy practices in CEE. In conducting such studies one should avoid mistakes of former studies of EA systems, for example, that relied upon formal, static, partial and context-insensitive criteria (Cherp and Antypas, forthcoming).

Local governments play a significant role in national environmental policy processes. This role consists of the complex tasks of implementing national (and international) policies, as well as formulating local policies and regulations. These complex roles and responsibilities in the environmental field of local governments are best summarised in Chapter 28 – entitled ‘Local Authorities in Support of Agenda 21’ – of Agenda 21, the key document accepted at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in 1992:

“Local authorities construct, operate and maintain

economic, social and environmental infrastructure, oversee planning processes,

establish local environmental policies and regulations and assist in implementing

national and sub-national environmental policies.”

Notwithstanding, local governments face a number of problems and challenges in fulfilling these complex roles and responsibilities. These include political problems of decentralisation and local democracy, as well as constraints in human, natural and financial resources. Furthermore, these problems occur in different shape in different locations, there is also a continuous evolution of both the problems and challenges, as well as the role of local and national governments in dealing with them (EEA, 1997).

Due to the complex tasks they face SEA is a particularly relevant tool for local and regional governments. Local governments make strategic decisions and set out plans for various aspects of local development, which all need to consider local needs and conditions. In addition, certain strategic plans at the national level (such as the National Development Plan in the EU, which is also being prepared in accession countries, such as Hungary) build upon local and regional development plans, hence decisions at the sub-national level can have significant impact for national policies.

In this regard, the way of and the extent to SEA applied at the local and regional government level is particularly important for both national environmental policymaking and local environmental management.

However, SEA is not the only environmental

decision support tool applicable at local and regional level. Environmental

management systems, programmes, action plans, auditing, and eco-budgeting

have all been developed and applied to a varying degree at local governments.

Yet, these tools are often developed and implemented independently and

have rarely been considered within an integrated framework of environmental

management.

2 THE ENVIRONMENTAL ROLE AND FUNCTIONS OF LOCAL GOVERNMENTS

The environmental aspects of local

government operations can only be understood in light of the general

roles and functions of local governments. These roles and functions, however,

depend on the time and location of local governments considered, and are

subjects to different political views and scientific discussions. It is

beyond the scope of this study to explore in detail the various aspects of

these views and discussions; however, some general considerations are given

here based upon a review of some key literature on the subject.

2.1. Theoretical models of local government operations

The name ‘local government’ suggests that it is about ‘locality’ and ‘government’. The locality element refers to the settlements, which are geographically defined human infrastructures built on natural conditions and where human activities concentrate (Csapóné, 2001 and Enyedi, 1999). Government relates to the practising of power, managing public affairs, which in modern times are linked to issues of democracy (Bánkuti, 1999). As Grey (1994) suggests government also implies in a political sense a certain level of ‘autonomy’, and most local governments have independent legal and political status.

With regard to the general roles of local governments in theory, Leach and Stewart (1992) identified three aspects of ‘justification’ for local governments. These include political (e.g. diffusion of power, political participation), economic (e.g. allocation, stabilisation and distribution) and socio-geographic (e.g. mediator of community competition and conflict) considerations. McNaughton (1998) considered three fundamental issues, which define the development of local governments: culture and tradition, efficiency and democracy. Soós (2001) identified four general duties of local governments: 1. policy-making and target setting, 2. policy implementation, 3. community service, and 4. realising democracy.

General discussions on British local politics in the late 1990s emphasised certain elements of local government theory, which is useful to mention here. McNaughton (1998) highlighted three dominant issues around which the main political trends and processes evolved: devolution, decentralisation and democratisation. These issues also recur in several publications on local politics internationally (see e.g. Blair, 2000, Soós 2001). Theoretic discussions on the administrative functions of local governments focused on the evolution from ‘direct service provision’ as a principal function to ‘enabling’ or ‘facilitating’ the services (Leach and Stewart, 1992, McNaughton, 1998, Corrigan, 1999). These discussions highlight the existing and possible differences in approaches to local governance at both local and national political levels.

Another pattern of local governance

is that elected local government is just one of the many agents and actors

involved in the local political and management process (Batty, 2001). These

other local actors include public and private sector agencies, quasi-autonomous

non-governmental organisations (QUANGOs), businesses and non-governmental

organisations (NGOs).

2.2. Local government environmental functions

The environmental role of local governments internationally has evolved through time. In the early 20th century in Europe, the main concern of local government was with public health and sanitation problems associated with rapid industrialization and urbanisation (Gresser et al., 1981; Ashworth, 1992). In the 1940s/ 1950s, the emphasis was on land use planning and post-war reconstruction (Barrett, 1995). The 1960s and early 1970s saw a heightened environmental concern in many countries with greater local government involvement in pollution control (Barrett & Therivel, 1991; Ashworth, 1992). From the 1970s and 1980s local governments started to function also as local environmental agencies. Since the late 1980s and especially since the Rio Summit in 1992, the environmental role of local governments has become even more multifaceted.

A practical structuring of the complex environmental roles and functions of local governments are provided in a UNEP Training Kit (2002) on municipal environmental management. From an environmental perspective the Kit identified three dimensions of local governments: political, administrative and of the community. The political dimension refers to decision-making and the practising of power at the municipal level. The administrative dimension represents the responsibilities and tasks of running and managing the municipalities’ infrastructure and social functions. The community dimension highlights the importance of local governments in representing and protecting the local community’s interest.

Arguably, one of the principal purposes of environmental management at local governments is to integrate the environmental concerns into all dimensions of their functions and operations (Erdmenger, 1998). This is fundamentally not different to the purpose of environmental management at business organisations.

The international context within

which local governments operate is reviewed in the next chapter.

2.3. International policy

and practice of environmental management at local governments

2.3.1. The international polciy

context

In the 1990s a number of high-level international conferences were held on sustainable development related issues. These conferences shaped the international policy environment and catalysed a similar process of policy development at the regional level (EEA, 1998). They also provided context and rationale for local authority action on sustainable development. Arguably, the two most significant international conferences were the Rio Earth Summit and Habitat II.

The United Nations’ Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), popularly known as the ‘Earth Summit’, was held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. The Earth Summit resulted in five official documents: Rio Declaration; Agenda 21; Biodiversity Convention; Climate Convention; and Forest Principles.

Agenda 21 has a particular resonance for local authorities as it recognised them as key players in the sustainability debate (Mittler, 2001). It has been estimated that almost two thirds of the actions in Agenda 21 require the involvement of local government (Grubb et al., 1993).

Agenda 21 devoted an entire chapter (Chapter 28) to local authorities as a result of active involvement by groups such as the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI), the United Towns Organization, European Commission delegates and others. The key message of Chapter 28 is that it called upon all local authorities/municipalities world-wide to draw up and implement local plans of action (Local Agenda 21) for sustainable development, in partnership with all stakeholders in the local community.

Certain scepticism was raised about

the real value of Agenda 21, given that it was not legally binding (Layard,

2001). Critics also argued that key obstacles to Agenda 21’s implementation

remained; including the focus on ‘the South’; and disregarding the changes

in national economic sovereignty as well as the role and responsibility

of transnational corporations (TNCs) (EEA, 1998). Despite these shortcomings,

Agenda 21 has had a major impact as it has provided a framework for discussion

on sustainable development, and holistic approaches and integrative strategies,

as well as initiated unparalleled action at the local level (see e.g. Rees,

1999).

Officially known as the Second UN Conference on Human Settlements (the first conference being held in Vancouver in 1976), Habitat II was organized to raise public awareness about the problems and potentials of human settlements, and to seek commitment from the world’s governments to make all locales of human habitation healthy, safe, just, and sustainable (UN 1996). Habitat II focused on the issues of provision of adequate shelter and livelihoods and the creation of sustainable human settlements. Habitat II launched the UNCHS’s ‘Best Practices Initiative’, an idea taken over from the European Commission’s Sustainable Cities Project (see below). Two final documents were issued at the conference: the ‘Istanbul Declaration’ and the Habitat Agenda. The 15-paragraph ‘Istanbul Declaration’ reaffirmed the commitment by governments to “better standards of living in larger freedom for all humankind” The Habitat Agenda: the World Plan of Action was, however, more substantive and directly relevant to agenda-setting and policy-making for local authorities as urban managers (EEA 1998).

There were certain criticisms made

about the documents stating that they were actually not operational plans.

As Cohen (1996) stressed “while the term ‘sustainable development’ was

mentioned repeatedly, little progress was made in suggesting how it could

be operationally applied to urban areas.” Also the Habitat II Conference

can be regarded as ‘supplementary’ to the Rio Earth Summit since it put

human needs at the centre of sustainable development and gave

less attention to environmental issues (Satterthwaite, 1997).

2.3.2 The environmental functions

of local governments in European practice

In current international practice, there is a great variation in the political and administrative set up and operation of local governments. Most of this variation stems from the varying state structures, ranging even in Europe from centralised unitary states such as the UK to federal states such as Germany. A 1994 comparative survey of environmental structures in local and regional authorities, conducted by the Council of European Municipalities and Regions (CEMR), provided a comprehensive overview of these variations around the following topics: finance, competences, responsibilities, partnerships and democratic processes (CEMR, 1994). The following paragraphs summarise the key findings of this European survey.

The lack of finance

was commonly perceived to be a major stumbling block to undertaking or

improving environmental management at local government. There are greater

variations in the legal competences and constitutional standings

of local governments. The constitution lays down the competences of local

governments in several countries, which include in Germany and Denmark,

for example, competences for public affairs, local affairs and issuing regulations

in their jurisdictions. In other countries, such as the Netherlands, specific

municipal or local government laws govern local authorities.

According to the survey, most European local authorities share some statutory service responsibilities such as: street cleaning, water supply, sewage and waste collection (but not always disposal and recycling), housing, police, fire brigade, parks, cemeteries and crematoria, cultural and recreational facilities, lighting, local roads, public transport, some educational, health, and other social services. However, there is considerable diversity in other areas, including traffic management, energy efficiency and conservation, toxic-waste disposal, land-use planning, air quality, promotion of eco-efficient products and services, groundwater protection, protection of water bodies, and economic development.

Partnerships, administrative style, openness, and relations with local social and economic actors are characterised by the level of application of mechanisms such as open information policies (e.g. toxic registers), strong public ‘right to know’ laws, public hearings on developments, legally binding public referenda on contentious issues. According to the survey there was a significant internal variation at a pan-European level. Countries such as Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands had applied more of these instruments, however, local governments in most countries were yet to follow these leading examples.

The survey also identified significant

variations in democratic processes, including political

traditions, state-society relations and customs of decision-making. These

variations were identified to be responsible for the development of different

national and regional environmental priorities. Priorities ranged from

in Greece: the battle against pollution, the establishment of more confident

NGOs, and the struggle to prise open municipal structures were identified

as priorities, through in Italy and Spain: the need for coordination of

initiatives, demands for decentralisation, awareness raising and public

participation, to in Germany and Austria: responding to issues of diversity,

economic security and North-South relations. Notwithstanding these differences

in emphasis, certain cross-cutting themes appeared to be common to all:

implementation and monitoring, gaining political support, connecting with

communities, achieving policy integration and synthesis.

3 LOCAL ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT IN HUNGARY

The following sections provide an

introduction to the local government system in Hungary as well as to the main

environmental issues Hungarian local governments face.

3.1. Local government in

Hungary

There are two levels of local government in Hungary: the municipality and the county. Municipalities are the basic units of the system and are organized by settlements, which in Hungary include villages, cities and cities with county rights. The middle tier of local government, consists of nineteen counties. The capital city, Budapest, has special legal status and has a two tier structure itself.

There are no hierarchical relations between the two levels of local government. According to Article 42 of the Hungarian Constitution, the fundamental rights of all local governments are equal. County local governments neither are superior organs to municipalities, nor do they have supervisory authority over them. The difference between the two levels lies in the administrative tasks delegated to each. Municipalities provide local public services to their settlements; counties have a subsidiary role in that they provide public services that settlements are not capable of performing, as well as those that have a regional character.

Municipal governments have broad responsibilities in service provision as set out the in the Act on Local Governments (1990). They can undertake any local public issue not prohibited by law provided that it does not jeopardize the fulfilment of obligatory functions and powers. Thus, local government tasks are distinguished as mandatory and optional.

Parliament and legal

provisions determine the mandatory functions and powers of local governments.

The principle functions of municipalities are set out by the Act on Local

Governments. Mandatory tasks prescribed by the act include the provision

of healthy drinking water, kindergarten education, primary school instruction

and education, basic health and welfare services, public lighting, local

public roads and public cemeteries, and the protection of the rights

of ethnic and national minorities.

A local government freely may undertake optional tasks determined on the basis of the requirements of the population and financial means available.

The Act on Local Governments, however, delegates more functions to local governments as general tasks. These include among others local development and land use planning, protection of the natural and built environment, drainage of rainwater and wastewater, local public transport, cleaning of public areas and provision of local energy supply.

Cities may be obliged by law to provide additional public services. The Act on Local Governments states that municipal governments may be authorized by parliamentary act to provide specific public services and to attend to other local tasks. Such obligations may be determined on the basis of the size, population or financial capabilities of the settlement. For example, cities must maintain fire brigades, technical rescue services and a wider range of social welfare services than villages.

Some major cities are conferred special legal status by the Act on Local Governments; these are the ‘cities with county rights’. The government of a city with county rights is a municipal government that also discharges the functions and powers of a county government. Its local government may form districts and may establish district offices.

According to the 1990 Act on Local Governments the county is defined as local government with a subsidiary role in local services provision. The county performs tasks that municipal governments are not obliged to provide, but its obligations are not enumerated specifically by the act. Additional public services of a regional character may be conferred upon the county by parliamentary act. In practice the main function of counties is maintenance of institutions providing public services, such as hospitals, secondary schools, museums, libraries, theaters, et cetera.

The capital of the country, Budapest, has a two-tiered system consisting of the self-government of the capital and those of its twenty-three districts. The municipal governments of the capital and its districts have independent functions and powers. The district governments independently fulfil the functions and powers of municipal governments. The government of the capital fulfils mandatory and voluntarily assumed municipal government functions and powers that affect the whole city or more than one district, as well as the those related to the special role of the capital within the country.

In practice the tasks and services provided by the two levels are not differentiated. On the basis of agreement, district governments may undertake—or the capital may delegate the organization of—certain public services that fall under the scope of functions and powers of the capital’s government, as long as the financial resources necessary for the fulfilment of such services simultaneously are identified.

Table 3.1. Structure of Hungarian local governments by type

|

Local government types |

Number |

|

Municipality |

3157 |

|

Districts of the Capital |

23 |

|

Cities with County Rights |

22 |

|

Towns |

199 |

|

Villages |

2913 |

|

Capital |

1 |

|

Counties |

19 |

|

TOTAL all levels of

LG |

3177 |

Over half of Hungarian local governments have fewer than 1,000 inhabitants,

and account for 8 percent of the total population (Table sdf). Other

than the Capital, which has a population of about 1.9 million, only 135

cities have more than 10,000 inhabitants, with a total of 4.1 million

inhabitants. Together, Budapest and cities with over 10,000 inhabitants

account for about 60 percent of the population.

Table 3.2. Structure of Hungarian municipalities by size

|

Size of municipality |

No. of municipalities |

Percentage of municipalities |

Total population (x 1000) |

Percentage of population |

|

> 1,000 |

1,730 |

55.2 |

783 |

7.8 |

|

1,000-5,000 |

1,144 |

36.5 |

2,420 |

24.1 |

|

5,000-10,000 |

123 |

3.9 |

924 |

9.2 |

|

10,000-100,000 |

129 |

4.1 |

2,953 |

29.4 |

|

100,000 < |

9 |

0.3 |

2,973 |

29.6 |

|

Total |

3,135 |

100.0 |

10,043 |

100.0 |

3.2. Local environmental

policy context

The municipal public sector is an important contributor to water and soil pollution. Municipal waste pollution of surface water is high (in Hungary, surface water in need of treatment exceeds eighty percent). In addition, the rate of suitably treated water is the same in the case of both industrial and municipal wastewater—about forty percent. Municipal wastewater discharge originates from households, institutions and industrial facilities; untreated wastewater discharge from these sources in canalized areas causes significant surface water pollution. The majority of sewage either is unpurified or is purified inadequately. In Hungary the ratio of biologically treated municipal wastewater is 42.3 percent, while that of advanced treated municipal wastewater is 5.9 percent. Especially the capital and large towns lag behind in treatment (1998). Illegal wastewater release into the river system is not a rare event.

Ground water pollution caused by the populace mainly is due to a lack of sewers; thus, households use the desiccation method. While 96-97 percent of the population in Hungary lives in areas with public water supply systems, 91.1 percent of the total number of dwellings have in-house water supply, while those with public sewerage only comprise 47.6 percent of the total. Pretreatment processes in industrial plants are often nonexistent, and another source of pollution is surface rainwater that is conducted back into drinking water reservoirs.

Municipal solid waste discharge is another polluting activity. About three million tons of waste generated is deposited in an orderly or legalized manner. More than 2,600 disposal sites are available for 3,155 local governments, two-thirds of which are in authorized locations, but only slightly more than 300 sites have the organizational and technical infrastructure to ensure appropriate treatment.

The number of sites in which there is organized collection of waste materials is estimated to be 1,000. The waste material of about 2,000 settlements is transported to abandoned quarries or to forest rims. Fifteen percent of disposal sites are regional and serve 100 settlements altogether.

The majority of disposal sites contribute to the pollution of ground water due to the absence of technical protection, especially nitrate contamination. The components of precipitation are absorbed by the soil and seep into the groundwater supply. Especially strong contamination results if waste material is placed in landfills near the ground water level without using proper technology. Waste disposal sites located near hydroelectric power stations represent a particular threat to water quality.

In Hungary, most of the potable water supply is derived from ground water, and the majority of such sources already comply with EU directives. However, arsenic contamination is a problem in certain areas, though this is believed to be a natural component of raw water. Bacterial and nitrogen contamination represents a more serious problem in other parts of the country, relating to both infiltration and inadequacy of chlorine residuals.

The key policy documents with regards to local environmental policy in Hungary fall into two main categories. The first consists of generic legislation establishing the generic tasks and responsibilities for local governments. The second group includes specific pieces of legislation prescribing particular duties and/or implementation means in the field of environment.

As discussed above the general duties of local governments are prescribed in national legislation. The 1990 Act on Local Governments prescribed only a few specific mandatory tasks for local governments, which did not specifically include environmental protection. However, the Act delegated several general duties to local governments, including “the protection of the natural and built environment”.

The main environmental legislation is the 1995 Act on the Environment. The Act required local governments to create municipal environmental programmes (MEPs), as well as to regulate its main environmental duties through local ordinance. The Act also provides for local governments to establish dedicated local environmental funds to finance environmental projects.

Most specific environmental requirements were developed in the field of waste management, as well as of water and wastewater. The key driving force in the development of the Hungarian regulatory was the EU accession process.

There is well established structure of environmental responsibilities among the various levels of government. The main task of central government is to ensure appropriate legislation and establish national programmes for environmental protection. The main responsibility of regional government authorities (environmental, water and health authorities) is to monitor and enforce legislation. As such, regional authorities monitor mainly the activities of the private sector (in particular, industry). Municipal governments are responsible for local issues, such as sewerage and waste management, and deal mainly with the public sector, or low risk private organisations, such as retailers and the service sector. (For example, air emissions from household appliances and from boilers with capacity lower tha 140 kWh are overseen by local governments, whereas the control of all other sources of air emissions are the responsibility of the regional environmental authorities.)

The 2000 Waste Management Act delegated local governments several specific responsibilities. The was developed in line with the 75/442/EEC Directive on Waste and provides a framework for action in the field of waste management in Hungary. The Act made municipal waste management a mandatory duty for local governments. In particular, according to the Act, local governments have to determine and regulate the means and conditions of the collection of municipal solid waste, including the duties of residents, as well as the conditions for service providers. Local governments will also have to prepare local waste management plans. The Act refers to waste segregation as a potential method which local governments can make mandatory within their jurisdiction.

The disposal of municipal waste to landfills was regulated by the Ministery of the Environment Decree No. 22/2001, in accordance with European Landfill Directive (1999/31/EC). The Decree introduced strict requirements concerning the opening and operation of municipal landfills. Importantly, the Decree also required detailed environmental investigations of all existing landfills to determine remediation and clean-up needs. Considering that most existing landfills were created and owned by local governments, this regulation had important implications for them.

By far the largest costs of implementing the EU Environmental

Acquis are associated with attaining compliance with the Urban Waste Water

Treatment Directive (91/271/EEC). Government Decision No. 2168/2000 and

the modification of the 1995 Act on Water Management established the basis

for implementing the Directive in Hungary. The scale of the problem required

that a National Program for Wastewater Canalisation and Treatment was developed

and central funding was allocated to its implementation. Nevertheless, according

to the legal requirements, local governments are ultimately responsible

for the provision of adequate collection and treatment of municipal sewage

in all settlements with a population equivalent of more than 2000.

4 PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT

Box 1. Development and spatial plans in Hungary

The development concept defines development objectives of a territory (country, city, etc.) and priorities for development programmes. It also provides information to and guides various actors in sector and spatial planning and regional development.

Following the elaboration of the development concept, a development programme is drawn up consisting of strategic and operative sections. The strategic section identifies short and medium-term tasks and the responsibilities for their implementation in line with the priorities established by the development concept. The operative programme is divided into sub-programmes and partial programmes and contains detailed operational and scheduling as well as financial plans, and specifies the method of execution and the parties in charge of it.

The spatial plan determines the long-term spatial (physical) structure of a given region. It provides for the utilisation and protection of regional features and resources, for environmental protection, for the location of infrastructure networks, for the land use and offers means of legal enforcement of compliance with the plan.

Source: adapted from Article 5 Act XXI of 1996 on regional development and spatial planningThe creation of development concepts and programmes is mandatory at the national, regional and county level. In addition, municipalities can set up municipal associations to prepare development concepts at the so-called micro-regional level. The appropriate development councils formally approve these concepts and programmes. The drafting of spatial plans is, however, mandatory at the national, county and municipal levels and they are approved by the national and county assemblies and the municipal councils of representatives, respectively (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1 The administration of development and spatial plans in Hungary

| Administrative level

|

Development

concept & programme |

Spatial

(land-use) plan |

||

| Preparation |

Approval by |

Preparation |

Approval by |

|

| National |

Mandatory |

Parliament |

Mandatory |

Parliament |

| Regional |

Mandatory |

Regional Development Council |

- |

- |

| County |

Mandatory |

County Development Council |

Mandatory |

County Assembly |

| Micro-region |

Optional |

Micro-regional Development Council |

- |

- |

| Municipality |

Optional |

Body of Representatives |

Mandatory |

Body of Representatives |

Decree No. 18/1998 (July 25) of the Ministry for Environment and Regional Policy regulates the structure, content and format of the development and spatial plans. In particular, it requires that the economic, social and environmental consequences of plan’s implementation are assessed and reported in each type of plan. In addition, public consultation on the draft plans is required by the Government Decree 184/1996 (December 11), which regulates the co-ordination and adoption of regional development concepts, programmes and plans.

In 2000, the Hungarian Agency for Regional Development and Country Planning (VÁTI) prepared a study on the state of implementation of the regional development policies and laws (VÁTI, 2001). The researchers analysed the regional development concepts and programmes prepared at the county and micro-regional level following the enactment of the 1996 Regional Development Act. The report identified 217 municipal associations that prepared concepts and programmes in addition to the ones on county levels. Only about 5 % of the settlements in Hungary chose not to take part in micro-regional cooperation through municipal associations. Their report stated that in terms of sectoral focus, about half of the development plans targeted agrarian and rural development and environmental protection. Environmental objectives were common at the county level, whereas rural programs were central at micro-regional level.

In addition to spatial and development plans, environmental considerations can be considered in local planning through the unique system of Municipal Environmental Programmes (MEPs) introduced by the 1995 framework Environment Act. The Act contains a statutory obligation for local governments to establish MEPs, but provides only a limited degree of guidance and does not set a specific deadline for the adoption of this measure. In subsequent years, some guidelines on preparing MEPs were developed, the most widely known, was issued by the Ministry of Environment (ÖKO Rt, 1998). Yet, it was only larger towns where local governments prepared their MEPs before 2000. From 2001 the preparation of MEPs became an eligible activity for funding from the Central Environmental Fund (CEF) which provided a major motivation for local governments for their development. Moreover, from 2002 local environmental development projects became eligible for funding only on the condition that the local government had an MEP prepared and the project was in line with its objectives.

In summary, several types of land-use and development plans are prepared at all levels of administration in Hungary. The relevant planning laws provide general requirements for incorporating environmental considerations in these plans and consulting the public in the process of their preparation. Though some of these requirements are apparently reflected in practice, it is clear that mainstreaming the environment in the planning processes can only be achieved by introducing more systematic tools such as SEA.

At the time of preparing this paper, SEA of land use plans was not specifically regulated in Hungary though very general provisions for SEA of national policies were established already in the 1995 framework Environment Act (Articles 43 and 44), which required such policies to be accompanied by the description of their environmental effects. This requirement has not been used in practice, except in the case of SEA of the Regional Operational Programme of the National Development Plan (ROP NDP) which can be considered as the only practical application of a full-scale SEA in Hungary.

At the time of writing this paper, the transposition of the EU SEA Directive (2001/42/EC) was being scheduled. This would be achieved by July 31st, 2004 through an amendment of the framework Environment Act with an article specifically dealing with SEA and issuing a special Cabinet’s Decree regulating the scope and the details of the SEA procedure.

5 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT TOOLS AT LOCAL GOVERNMENTS

By 2003 complex environmental management tools (such as EMS) were hardly applied by Hungarian local governments. EMS was implemented at the local government of the city of Miskolc – however, there were no other municipalities known that would have applied EMS or ecoBUDGET or any other qualified tools.

The uptake of the quality management system (QMS) according to ISO 9001/2 became somewhat more wide-spread among local governments. In particular, some of the larger municipalities, the so called ‘cities with county rights’, as well as several district governments of Budapest carried out projects to implement QMSs and to have the systems certified. However, there is no central register for ISO certifications, therefore it could only be estimated based upon publicly available sources that certified quality management system was applied at less than 5% of all LGs in 2002.

5.1 EMS at municipal enterprises

A ‘greener’ picture may be drawn of the municipal service companies fully or partially owned by local governments. In most towns local governments have established business or not-for-profit enterprises to provide a lot of the municipal environmental services, such as municipal waste management, street cleaning, management of public areas and green spaces, etc. These enterprises are typically entitled to charge fees for their services but are also funded from municipal budgets. This already indicates they special feature representing a ‘transition’ between a public organization and a business enterprise.

Due to the nature of the ISO scheme there is no central register for ISO 14001 certified companies. However, a widely accepted source of information in Hungary is the inventory of ISO 14001 certified companies voluntarily operated by KÖVET, the Hungarian affiliate of the International Network for Environmental Management. According to the figures in January 2003 there were 493 companies in Hungary certified against the ISO 14001 standard.

It was possible to establish from the list that 15% of the certified companies were various environmental service providers (mainly waste service companies, environmental engineering firms, as well as consultancies) and about 8% of the total were municipal enterprises, wholly or partially owned by local governments. Perhaps surprisingly, seven of these were medical institutions (hospitals and clinics), which were fully owned by local or regional governments.

Typically the initiative for EMS implementation came from the enterprises themselves, which recognise the importance of better management and enhanced reputation earlier then local governments. In case of Miskolc, however, the EMAS implementation project already from its design involved the participation of a municipal enterprise (the local public transport company), in addition to the local government.

5.2 Government policies and guides on EMS at local governments

The ISO 14001 international standard was translated and adopted as a Hungarian standard in 1997. Since then the implementation and certification of EMSs at private enterprises according to ISO 14001 was supported by a few government guides and events and more importantly by central funds. Until 2001, the application for these funds was available to all business organizations (and not for local governments). From 2001 there were only four main groups of eligible companies, including certain environmental service providers (waste and wastewater treatment companies). Interesting to note that this fund is managed by the Ministry of Economy and not by the Ministry of Environment.

Many guides on local environmental management were produced during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Several of these (such as Öko Rt, 1998; Bándi, 1999, KGI, 1999) made reference to the LA-EMAS model that was developed in the UK, and recommended local governments to consider its application. However, there were no governmental programmes or incentives that would have actively promoted the implementation of EMS among local governments.

From 1996 the Central Environmental Fund (formerly known as KKA, more recently as KAC) was available for certain environmental projects carried out at the local government level. It was, however, only after 2000 that local governments could apply for funding to support the preparation of local environmental programs.

The (revised) EMAS regulation was formally adopted by Hungarian regulations in 2003 allowing participation for all kinds of organisations including local governments. However, the regulation will come into force only at the date Hungary joins the EU. A formal reference to EMAS was already added to the Environment Act. Until early 2003 there were no central governmental programme aiming to promote participation in the EMAS scheme in Hungary. The only existing experience with EMS implementation among Hungarian local governments is the case of Miskolc.

5.3 Municipal environmental programmes

Introduction

In 1995, the first comprehensive Environment Act introduced a statutory obligation for local governments to establish Municipal Environmental Programmes (MEPs). Since its introduction MEP has become a unique environmental management tool for Hungarian local governments. It is unique because it was introduced only in Hungary and it was not based upon any existing international tools. Nevertheless, it is an environmental management tool and as such it resembles many of the characteristics of other tools. The specific and common features of MEPs are discussed in this section.

The history so far

Besides introducing it the 1995 Act provided only some degree of instructions on the implementation of MEPs. The Act set no deadline for local governments with regards to the development of the programmes. Neither were any further policy guidelines, incentives or other related instruments introduced by central government to initiate local action. Even counteracting was the fact that the Act required the government to prepare a national programme, which took two years to be drafted and formally adopted by Parliament in 1997. Consequently, most local governments were keen to delay the development of their own programmes for several years after 1995. The adoption of the National Environmental Programme created some moral incentive for local governments, as well as it provided a template for an environmental programme.

In consequent years a limited number of guidance documents were also published to support the efforts of local governments in preparation of MEPs. Most notable of these was the guide issued by the Ministry of Environment (ÖKO Rt, 1998) with support from the European Union’s PHARE programme. The guide provided a good overview of the programming process and had a clear focus on embedding the MEPs into the legally prescribed responsibilities of the local governments. Its main value was, however, that the guide was disseminated among some 500 local governments and thus served as a practical reference. It was also reproduced in electronic format and included in a subsequent guide on micro-regional environmental management issued as a CD-ROM (Szarvas, 2002), which was disseminated among nearly 300 micro-regions.

There were also some other guides produced which had, however, less impact due to mainly their limited availability for local governments. Some of these publications were developed with foreign aid (e.g. FÖK, 1997, Flachner and F. Nagy, 1998, Markowitz, 2000), and their particular feature was the emphasis put on community involvement and the limited reference made to the legal requirements. Yet, it was only larger towns where local governments prepared their MEPs before 2000 – most municipalities were reluctant to act even half a decade after the legal requirement was enacted.

In 2001 more effective incentives were introduced by central government related to grants available from the Central Environmental Fund (CEF). The CEF was established in 1992 and became the largest governmental fund available in 1990s for subsidizing local action. CEF money was allocated to individual local projects through centralised tendering and the share of central funding was in the range of 30 to 100 % of total costs.

From 2001 the preparation of an MEP became also an eligible activity for funding from the CEF and provided a major motivation for local governments. In 2002, another incentive was introduced related the CEF: local environmental development projects (typically infrastructure projects, such as waste and wastewater treatment) became eligible for funding only in condition that the local government had an MEP prepared and the project was in line with the local programme objectives.

The situation by early 2003

There is no central statistics available on the number of MEPs prepared in the country. A small number of studies and surveys are available, however, to allow a general overview.

One “official” piece of information on MEPs was released in December 2002. In a written response to an MP’s formal query in Parliament on the status of preparation of MEPs at local governments the prevailing Minster for Environment, Ms Mária Kóródi, provided somewhat controversial information.

Based upon data provided by the regional environmental inspectorates the Minister reported that 189, that is 5.9% of the municipalities had their MEPs prepared by late 2002. In a further 12 micro-regions municipalities joined efforts and developed their common environmental programmes at the micro-regional level. No information was provided on the number of municipalities participating in these 12 regional initiatives. The Minister also reported that 17 of the 19 counties had also their MEPs developed.

However, the Minister’s information was rather limited as far as it only included those MEPs that were submitted to the regional inspectorates. The inspectorates were only presented the MEPs for information, they did not have any legal right to approve/reject or any obligation to collect such information on MEPs.

The available research information indicates a somewhat greater rate of compliance by municipalities with the legal requirement on the development of MEPs than the Minister’s information. Based upon a survey of 600 local governments representing all types of settlements, Pickvance (2002) calculated that 95% of the relatively large cities with county rights, 70% of the Budapest districts, 55% of the towns, 35% of the large villages, and only 20% of the small villages had their environmental programmes prepared by December 1998.

The 95% figure for the cities with county rights practically suggested that 21 of the 22 cities had already prepared the MEP by 1998. However, about the same time there were two surveys undertaken specifically focusing on these cities: the Geoview survey in 1998-1999, the Centre for Environmental Studies (CES) survey in 1999. Interestingly, the Geoview study found 16, the CES survey identified 19 of the 22 cities that had prepared an MEP. While it was not possible to confirm the real situation for those years, based upon a quick check over the internet and telephone it was established that by 2002 all provincial cities had their MEPs prepared.

There is no information available from any other surveys or statistics on the number of MEPs prepared by either the districts of Budapest or other towns. The capital itself was quite late in meeting the legal requirement. After long years of preparation the city’s environmental programme was only completed by March 2002.

A brief telephone survey was conducted in 2003 to provide a snapshot of the prevailing situation. 30 randomly selected municipalities were interviewed representing population sizes in a range of 2.000 to 20,000. Of those interviewed fifteen (50%) had already an MEP developed and further five (20%) had a programme under preparation. There were ten larger municipalities (population over 20,000) interviewed and of those 70% had a MEP. For the twenty smaller ones (population between 2,000 and 20,000) the corresponding figure was 40%, with no significant correlation with size within the group.

The Ministry of Environment sponsored another survey in 2001 that revealed a fairly similar picture on towns and villages to that of Pickvance from 1998 (Szarvas, 2002). The survey focused on micro-regions and did not distinguish between towns and villages. It identified that at least one MEP was prepared in 50% of the regions participating in the survey and in about 28% more than one MEP was set out. Assuming that in most micro-regions the towns were first to prepare their programme we can estimate that a very small portion of the villages had their MEPs prepared even by 2001 – six years after the legal obligation was issued. The survey also revealed that over half of the programmes in the micro-regions were prepared after 2000.

In his study Pickvance (2002) distinguished between three regions of the country: the North-west including Budapest and the affluent western part of the country, the South covering the southern part of the Great Plain and the south-western counties, and the North-east including the poorest counties of Hungary located in the north-east. However, neither his study nor any other studies or surveys could identify significant regional differences within Hungary with regards to the proportion of local governments with MEPs.

6 THE LEVEL OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT AT CASE STUDY MUNICIPALITIES

In the following section case study municipalities and their environmental programmes are examined for the presence of these elements. The assessment is based upon information gained from interviews with key local government representatives, reviews of documents, in particular the environmental programmes of the local governments.

The assessment of the MEP documents offers a window not only to observe the design and anticipated implementation of these programmes, but also to understand the environmental perspective and management priorities of the local governments more generally. This provides for a comparison of these perspectives and priorities across LGs of different types, sizes and levels of complexity.

One should expect considerable variance in the practice of selecting the environmental issues for consideration, and in determinations of priorities and selections of objectives and targets among them. Some reasons for such variance are obvious and appropriate. Examples include differences in differences in size, geographic locations; and differences in the environmental conditions in which they operate, which would lead to differences in environmental significance in different places. Other likely reasons for variation include differences in perceptions and priorities on the part of those developing the MEP: environmental coordinators, external consultants and other experts, community and NGO stakeholders if they are involved, etc.

The assessment also allows for a comparison between EMS and MEP as management tools. The objectives of this comparison are to establish the differences and similarities between these tools and to identify potential linkages between their applications.

There are obvious similarities and differences in the principal objectives of implementing an EMS or an MEP. An EMS is about systematically designing and implementing an organisation’s environmental responsibilities, as well as establishing mechanisms for reviewing these activities. An MEP is a tool for planning the environmental tasks of a local government with a limited focus on their review.

Yet, in a larger context both tools are designed for improving the environmental performance of the organisation that applies them. The success of their application can often only be assessed if considered in a larger context. Consequently, the following review applies the approach of the EMS model as described by ISO 14001 and EMAS, and assesses the local governments’ environmental management system through their environmental programmes as well as their management practices. The case studies presented here include a micro-region of eight small villages (Sárvíz Micro-Region), two towns (Orosháza and Hatvan), and a county (Pest County).

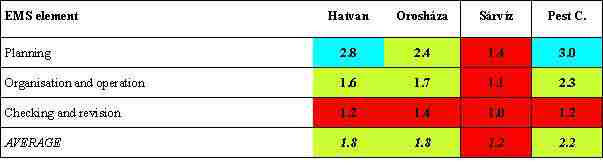

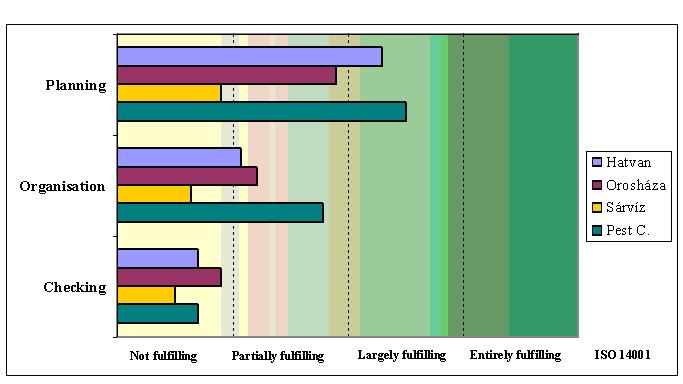

The case studies indicated an overall rather limited environmental management

capacity at Hungarian local governments. Of the three main groups of management

system elements clearly only planning tools were applied to a considerable

level. The application of organisational tools was found to be rather limited,

whereas tools of checking and revision were basically absent (see Table

6.1).

Table 6.1 Summary of the findings on the application

of EMS elements at the case studies

Note: On a scale 1 – entirely fulfilling

to 4 – not fulfilling the requirements of the ISO 14001 component

In comparison of the local governments by size most

striking is the great difference between the villages of the Sárvíz Micro-region

and the other larger LGs. The case study villages seemed to lack fundamental

management skills and capacities. This is indicative of a major problem

of Hungarian local government administrative system. Although the combined

size of the village governments and the represented populations make up the

size of a medium town, the Micro-region is not a real administrative level

in Hungary. The villages comprising the association did maintain their individual

local governments with small supporting administrations. Instead of uniting

their management capacities and sharing the tasks between each other, each

village had designated responsibilities for the same limited number of functions.

This organisational setting proves inefficient not only in environmental

management efforts but in many administrative tasks.

Among the other case studies the difference is not

so significant and only notable in relation to the planning elements. As

described at the relevant section, this difference was identified in the

assessment of the environmental programmes. Pest County and Hatvan were identified

to fulfil the requirements of the ISO 14001 EMS for planning to a greater

extent than Orosháza.

The organisational and operational capacities of the

larger case study administrations were rated as only partially adequate

to the standardised EMS requirements. The main shortcomings were observed

in relation to controlling the administration’s own operations, including

emergencies. While procedures for assigning general responsibilities, for

document control, and internal communications were established for the administrations

in general, the consequences and specific requirements from an environmental

point of view were not considered. In this regard, the presence of ISO 9000

compatible quality management systems provided some founding stones for

EMSs, yet, QMSs typically were short of covering environmental aspects.

Figure 6.1 The presence of EMS elements at the case

study LGs

The most crucial deficiency of the case study environmental

management capacities from the EMS viewpoint was in the field of checking

and corrective actions. Fundamentally, this indicated a substantial lack

of efforts from local governments to monitor and revise their environmental

decisions and activities. Again, a quality management system could provide

the backbone for such management activities, yet, they need to be filled

with environmental substance.

While the lack of EMS capacity at villages might have

been predictable it is notable that even planning elements were lacking

in spite of the presence of an environmental programme. This indicates that

the mere presence of a MEP may not be indicative of a local government’s

environmental performance without an assessment of the content, design and

implementation of such programme. The cases also underscored that having an

MEP would not necessarily mean that environmental planning at a local government

is undertaken according to the EMS requirements.

Overall, the practice of MEPs highlighted both the

values and the shortcomings of this tool in comparison to EMS. MEPs were

found to be useful for local planning of environmental tasks. Specifically,

they were strong in identifying the problems and areas for intervention at

the municipal level, that is the problems relating to the entire locality

in question. However, neither the MEPs, nor any other tools or activities

seemed to identify and tackle the specific responsibilities of local governments.

The EMS concept suggests that the organisation should identify and prioritise

the areas it needs to and can deal with. Hungarian local governments seemed

to wish to tackle all or many problems in their MEPs, however, at the same

time they were found short in assessing and developing the necessary capacities.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Hungary has a developed spatial and development planning

system which requires preparation of land-use and other plans at different

administrative levels. At present, there are no formal SEA requirements

for land-use plans in Hungary. The current planning regulation requires assessment

of environmental consequences of land-use plans, however very few such assessments

have been conducted, they have not been systematically evaluated and most

likely fall far short of procedural and methodological “best practice” of

SEA. In general, the concept of SEA is not widely familiar in Hungary since

SEAs of other types of policies, plans and programmes is also not legally

required.

There are, however, significant opportunities for introducing

an effective SEA system in Hungary. The first such opportunity is the forthcoming

adoption by Ministerial Regulations of the EU SEA Directive and the accession

to the Kiev SEA Protocol. This process of formulating and implementing SEA

policies will be led by the Ministry of Environment, which has one of the

most extensive experience, among Central European countries, in Environmental

Assessment. As the lessons of the pilot application of SEA to the Regional

Operation Programme of the National Development Plan demonstrate, the SEA

actors and stakeholders in Hungary have sufficient capacity to undertake SEA

and integrate it in the planning processes. Emerging guidance on SEA, the

ability of environmental authorities to monitor and critically evaluate the

system as well as participation of SEA professionals in international networks

can further strengthen this capacity in the future.

Furthermore, Hungarian local governments have obtained

significant experience in the preparation of municipal environmental programmes.

This experience contributes to an improved practice in integrating environmental

considerations into the local planning process. However, as this study reveals,

municipalities still lack the skills and capacities to adopt full scale

and comprehensive environmental management systems.

There is also only limited experience of applying comprehensive

management tools, such as EMS at Hungarian local governments. So far only

the municipality of Miskolc has adopted an environmental management system,

that has already been certified against ISO 14001, as well as verified agaisnt

the requirements of EMAS. The uptake of the quality management system

(QMS) according to ISO 9001/2 became somewhat more wide-spread among local

governments. In particular, some of the larger municipalities, the so called

‘cities with county rights’, as well as several district governments of Budapest

carried out projects to implement QMSs and to have the systems certified.

However, there is no central register for ISO certifications, therefore it

could only be estimated based upon publicly available sources that certified

quality management system was applied at less than 5% of all LGs in 2002.

There are a number of challenges of introducing effective

local environmental policies in Hungary. One of them is the very large number

of local governments who are obliged to develop land use plans and comply

with all regulations central government establish. With regars to the proposed

SEA regulations, clearly, only some of these plans should be made subject

to SEA, otherwise there is a danger of repeating Estonian experience where

the requirement to undertake SEA of all land-use plans was repelled after

three years of unsuccessfully trying to cover the whole range of planning

documents (Peterson 2004). Another related problem is that the requirements

for small and large local governments are the same. It is yet to be seen

whether such one-size-fits-all approach will be conducive for effective

integration of environmental aspects in widely different planning and decision-making

processes.

In summary, the strength of the Hungarian land use planning system and the opportunities for integrating into it effective SEA provisions are likely to ensure that an effective SEA system can be established in the near future. With regards to other environmental management tools the wide-spread adoption depends mainly on central government policies, and the development of local environmental capacities.