HEALTH AND EU ACCESSION:

SOME CHALLENGES TO THE USE OF HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT

IN HUNGARY

Margit OHR

International Policy Fellow

Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Summary of findings and recommendations

- Introduction

- Policy research questions

- Methods

- Health Impact Assessment in the European Union

- Development of HIA in Europe

- The EU Public Health Programme

- HIA in the EU

- Case studies

- HIA in the UK

- HIA in the Netherlands

- Situational analysis in Hungary

- Policy context in Hungary

- Factors affecting use of HIA in Hungary

- Comparison of factors affecting HIA in Hungary and the EU

- Conclusions and policy recommendations

- Establishing a legal framework for HIA in Hungary

- Building capacity

- Institutional development

- References

Tables

1. Factors affecting the use of HIA in Wales

2. HIA’s coordinated or produced by NSPH

3. Factors affecting the use of HIA in Hungary

Figures

1. Key stages in HIA

2. Perceived barriers to using HIA in government policymaking in European

countries

3. Comments on HIA made by Tessa Jowell MP [former] Minister of State

for Public Health

4. main objectives of the Dutch plan of action to develop HIA in 1995

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Open Society Institute International Policy

Fellowship Program for awarding me a Fellowship that enabled me to

carry out this policy research study. In particular, Pamela Kilpadi

(IPF Program Manager, Mladen Momcilivic (IPF Program Coordinator)

and Csilla Kaposvari (Public Health Fellows Coordinator) gave me support

and encouragement during my fellowship year (2002/2003).

I would like to express gratitude to my mentors (Hungarian

mentor: Dr. Mihály Kökény, Parliamentary Secretary

of State, Ministry of Health, Social and Family Affairs; International

mentor: Dr. Martin Birley, Director, International Health IMPACT Assessment

Consortium, University of Liverpool). Both gave me their time and

helped to inform the development of my research and access to networking

and training opportunities. In addition, Dr Birley facilitated my

involvement as a third party in a current EU-funded (SANCO) project:

Policy Health Impact Assessment for the European Union.

I am grateful to all of the people I interviewed for

their willing participation and interest in the research.

Mention must also go to Ceri Breeze of the Public Health

Strategy Division, Welsh Assembly Government, for involving me to

the Pan-European HIA Survey 2002 and to his colleagues Heather Giles

and Marc Boggett for they support of these work.

Finally I would like to thank to Edit Sebestyén

(health promotion expert) for her research assistant work that helped

me to carry out this work.

If readers have comments or feedback on this paper,

please contact me at ohr@policy.hu

Summary of findings and recommendations

Introduction

This paper is one outcome of my research work within the International

Policy Fellowship Programme of the Open Society Institute, Budapest,

Hungary during the 2002/2003 fellowship year.

The paper discusses opportunities and barriers to the

use of Health Impact Assessment in Hungary and makes some key policy

recommendations relating to the implementation of HIA in the context

of EU Accession.

The paper starts by providing some relevant background

on the use of HIA in the European Union and then presents more detailed

case studies based on experience of using HIA in the UK and The Netherlands.

It then goes on to identify and assess the current situation in Hungary

with particular attention to opportunities and barriers to understanding

and using HIA.

Aims and objectives of study

This study is the first step to look at and analyse all the significant

factors that can be supportive and barriers to the implementation

of HIA into the national decision making process. The aim of the study

is to identify these factors and by dealing with them prepare the

ground for capacity building for HIA.

Key findings

The key findings of this study relate to the following categories:

evidence, political/policy, institutional and resources. Examination

of the use of HIA in the EU and especially for this study, in the

UK and Netherlands, show that there remain significant barriers to

the use of HIA. However, the policy context is broadly supportive

of efforts to use HIA in both the UK and Netherlands. For example,

key policy drivers are: evidence-based action, intersectoral responses

and community participation in policy and planning, to complex policy

challenges (poverty, sustainable development, health inequalities).

By contrast, in Hungary:

- there is understanding of the complex policy challenges facing

Government. However, policy design and critically, implementation

is still pursued through sectors and sectoral interest groups

rather than developing more flexible, intersectoral means of both

identifying, designing and delivering action. In part this reflects

a lack of investment in modernising public administration, especially

in the health sector

- relatedly, an evidence-based working culture is not widespread

in policy and professional arenas

- finally, policy and strategy is still largely developed by

small closed groups of expert and bureaucratic interests lacking

transparency and meaningful engagement with wider stakeholder

interests.

The assumption informing this research was that EU Accession would

stimulate some of the changes necessary to modernise policy making/public

administration and enable the adoption and development of relevant

methods such as HIA. So close to EU Accession, this research shows

that in Hungary commitment to and investment in dealing with

policy and public administration development e.g. as a platform for

applying HIA methodology, is not obvious. Effective capacity building

will need educational, institutional and strategic level investment,

not least to tackle all the political and more seriously, the institutional-cultural

barriers to development.

Recommendations

The main recommendations are given below.

- Developing capacity and confidence in HIA should be part of

a broader effort to modernise policy making and institutions in

Hungary

- Carrying out HIA should be an essential part of government

planning and decision making in order to place health in the centre

of the decision making process.

- Under the Hungarian system, the requirement for HIA should

be regulated by law with clear lines of accountability through

the Minister for Health, Social and Family Affairs ultimately

reporting to Parliament

- Developing capacity (strategic, institutional and educational)

for HIA should be championed by the ‘modernising’ centre of gravity

in the Hungarian Public Administration

- Responsibility for guiding implementation of HIA across Government

should be located in a background institution working mainly in

relation to the Ministry of Health, Social and Family Affairs,

Ministry of Finance and the Prime Minister’s Office.

Key words: modernisation, health impact assessment, policy,

barriers, opportunities, comparison, capacity building, Gothenburg

Consensus statement, England, Scotland, Wales, Hungary, good practice,

Netherlands, European Union, World Health Organization

1. INTRODUCTION

EU competence in health is not limited to simply to activity labelled

health or public health. Under the terms of the Amsterdam Treaty,

there is a specific requirement that

a high level of human health protection be ensured in

the definition and implementation of all Community policies and

actions (Article 152)

This means that a broad range of activity (e.g. related to the Internal

Market, structural funds, social affairs, social inclusion, agriculture,

the environment, trade and development policy) must be appraised for

its potential impact on the health and well being of EU citizens.

Hungary is expected to join the EU in May 2004. In this

context the purpose of the work reported in this paper was to explore

factors that might affect the use of Health Impact Assessment in Hungary.

Two main sources of information inform this paper: (i) published experience

from among EU member states and (ii) findings from indepth interviews

with Hungarian stakeholders.

The ultimate goal of this work is to contribute to first

steps to build capacity within the Hungarian system to conduct health

impact assessment of any relevant policy or programme at national

level .

1.1 Policy research questions

The following research questions were identified at the start of the

Fellowship and then explored during the year:

- What might be considered as good practice in health impact

assessment?

- Do stakeholders in Hungary currently consider the health

impacts of, especially, non-health sector policies?

- Is the requirement for HIA considered, as a consequence

of EU Accession?

- What capacity and capability exists within Hungary to

use HIA methods as a systematic means of appraising the potential

and actual health impacts of policy?

- What actions could be taken to improve understanding,

confidence and expertise in HIA in Hungary?

1.2 Methods

The research process and methods used are summarised

below:

Review of HIA methods and practice:

- library and internet searches (February-March

2002)

- participation in IMPACT training course

(Liverpool, April-May 2002)

- participation in a Department of Health

meeting for EU Accession Countries to look at public health development

needs (London, April 2002)

- participation in IAIA Conference (The

Hague, June 2002)

- third party participation in EU (SANCO)

funded project: Policy Health Impact Assessment for the EU (August,

2002)

- Hungarian respondent to the Pan-European

HIA Survey (April 2002)

Situational analysis in Hungary:

- in-depth interviews with Hungarian

stakeholders (n=10 representing - Ministry of Health, Social and

Family Affairs, National Public Health and Medical Officer Service,

Universities, National Governmental Agencies, Ministry of Environment,

local experts and other professional colleagues) (Budapest, April-December

2002)

- development of policy briefing paper

on HIA for Parliamentary State Secretary at Ministry of Health,

Social and Family Affairs (Budapest, June, 2002)

- membership of an Advisory Group on

Capacity Building for Public Health convened under the National

Public Health Programme (Budapest, October 2002)

As the above diagram implies, it was sometimes hard to distinguish

between the policy research project, professional development and

participation in the policy process at both Hungarian and EU level

during the Fellowship year. Understanding of health impact assessment

and its application was developed through examining available literature

and by the opportunistic use of professional development and networking

opportunities identified during the fellowship year. Paralleling this

were opportunities to inform policy and programme developments in

Hungary and to access networks of key national and local stakeholders

developed over the previous eight years of working at a national agency

in Hungary.

The Hungarian data was collected by interviews with

key Hungarian stakeholders and published and unpublished public health

policy documents. I couldn’t use the survey methodology, like other

European countries in the Pan-European survey, because Hungary was

not in the position to answer for the questionnaire in details. But

I could use the questionnaire as an interview guide for my in-depth

interviews. The questionnaire was structured around several key themes:

• Broad policy context

• Awareness and understanding of health impact assessment

• Use of health impact assessment to date

• Other approaches and other forms of impact assessment

• Issues related to developing further the use of health

impact assessment

I asked the respondents to feel free not the answer

for those questions that are not relevant to them. All interviews

were conducted in Hungarian and they were then fully transcribed.

The resulting transcripts were read several times to better understand

the information being provided by informants. After this, the transcripts

were examined again to identify shared and different issues. These

were then grouped under opportunities and barriers categories for

further analysis. For more in-depth analysis I created new sub-categories:

evidence, political/policy, institutional, resources and I did comparison

with the Wales data as well.

2. HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT IN THE EUROPEAN UNION

This section provides some background to the development of HIA in

Europe and especially the legitimacy and requirement for HIA given

by the European Union in its conduct and the conduct of member states

and pre-Accession countries.

2.1 Development of HIA in Europe

The development of HIA in Canada, Europe and elsewhere was facilitated

by the emergence and acceptance of now overwhelming contemporary (and

historical) evidence that

- historically, the greatest improvements in people’s health

have come not from the health sector (important as this sector

is in supporting health improvement) but from social and economic

changes that improve the quality of people’s lives (Ziglio et

al 2000; Levin and Ziglio 1996)

- currently, the social environment and economic conditions

are a major influence on health status and outcomes at individual,

community and population levels (e.g. Leung and Wong, 2002; Lavis

and Sullivan, 1999; Marmot and Wilkinson, 1999; Gillies, 1998;

Blane, Brunner and Wilkinson, 1996; Wilkinson, 1996).

What this means is that the health care sector has less impact on

and responsibility for changes in mortality, morbidity and other health

status indicators than perhaps the public and many politicians had

thought.

Work by the WHO Centre for Health Policy (ECHP Policy

Learning Curve Series 2001, Number 4; 2001, HIA Discussion papers

Number 1) and others (e.g. OECD/PUMA 2000, Cabinet Office 2000) demonstrate

that in many countries there is understanding that proposed policy

decisions in one sector may impact on outcomes in other sectors. For

example, this has lead in some countries to the development of tools

and methods to assess the impact of economic and social development

policy decisions on the environment. The purpose of such an assessment

is to: improve knowledge about the potential or actual impact of a

policy or programme; inform decision makers and any affected communities;

and enable changes to be made to proposed policies/programmes in order

to help manage negative impacts and promote positive impacts.

Building on experience and learning from environmental

and social impact assessment work, there has been increasing interest

in health impact assessment. Development of HIA has varied according

to circumstances in different countries and the interests of early

champions. For example, in the UK HIA was developed and applied at

local level with little national coordination and application in contrast

to its development in The Netherlands.

This fragmented pattern of development led to understanding

of the need to develop a shared understanding about the core features

of HIA through an international exchange of experience and innovation.

An event in Sweden in December 1999 produced the Gothenburg Consensus

Statement on Health Impact Assessment. According to this statement,

HIA is defined as

Health Impact Assessment is a combination of procedures,

methods and tools by which a policy, program or project may be judged

as to its potential effects on the health of a population, and the

distribution of those effects within the population.

The important common elements of HIA were also set out (see Figure

1).

Figure 1: Key stages in HIA

- screening the potential policy or

programme for linkages with health. If the available information

is limited then the scope of further action has to be agreed

- scoping of HIA which helps identify:

which potential (in)direct health impacts of the policy/programme

need to be better explored; for which specific population

groups; using which methods; resources; who takes part; and

over what timeframe

- appraisal of the HIA report which

may lead to request to add information and reappraisal

- action adjusting the proposed decision

or intention therby acting on the results of the HIA

- monitoring and evaluation of expected

impacts.

2.2 The EU Public Health programme

The new EU Public Health Programme (2003-2008) was implemented on

January 1, 2003. It is a key instrument underpinning the development

of the Community’s Health Strategy. The main objectives of the new

EU Public Health Programme are:

- to improve information and knowledge for the development

of public health

- to enhance the capability of responding rapidly

and in a coordinated fashion to health threats

- to promote health and prevent disease through addressing

health determinants across all policies and activities.

To accomplish these objectives the Programme is intended to contribute

to:

- ensuring a high level of human health protection

in the definition and implementation of all Community policies

and activities through the promotion of an integrated and

inter-sectoral health strategy

- tackling inequalities in health

- encouraging cooperation between Member States in

the areas covered by Article 152 of the Amsterdam Treaty

The Programme will rely on work in four main areas: cross cutting

themes, health information, health threats and health determinants.

Health impact assessment is an example of action required within the

cross cutting theme element.

2.3 HIA in the EU

Despite growing investment in and understanding of HIA methods and

tools (see 2.1 above) relatively little was known until recently about

the application of HIA within the EU. To inform the future development

of health impact assessment within individual member states as part

of the European Community’s Public Health Programme (see 2.2 above),

a pan-European survey of health impact assessment at national government

level has been undertaken. The survey, which covered EU Member States,

accession States and European Economic Area countries, examined perspectives

on, and use of, health impact assessment at national governmental

level. The survey explored the barriers that exist or may be encountered.

The following diagram summarises the results (Breeze C, 2003, in press)

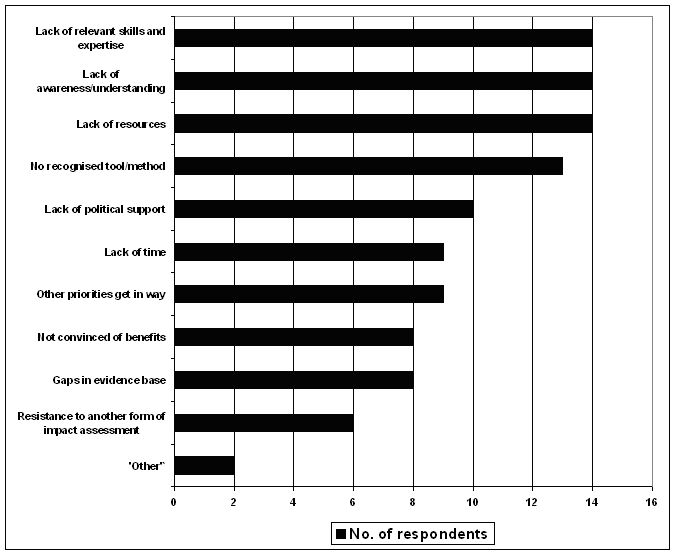

Figure 2: Perceived barriers to using health impact

assessment in government policymaking in European countries

Source: Welsh Assembly Government, 2002

What Figure 2 shows are two main types of problem in getting HIA

accepted and used as part of the policy process: (i) lack of understanding

of the need for and benefits of using HIA (ii) lack of capacity (skills,

expertise and resources and methods). These findings seem surprising

given the weight of evidence outlined in 2.1 above. They suggest a

need to improve the sharing of knowledge and expertise between academic/professional

experts and policy makers and the need to invest in HIA as a normal

part of the policy making process. Recognition of the need for HIA

in the new EU Public Health Programme and the linkage between a broad

range of Community competencies and health in the Amsterdam Treaty

should support wider adoption of HIA.

3. CASE STUDIES OF HIA IN THE UK AND NETHERLANDS

This section provides a more detailed look at two

contrasting developments of HIA, in the UK and in The Netherlands.

In both countries HIA has been developed and applied pragmatically.

However, the most significant difference between the two has been

the use of HIA at local/regional level in the UK and the more systematic

funding and use of HIA at national level in The Netherlands.

3. 1 HIA in the UK

In the UK, public health professionals and academics were early advocates

for HIA (Scott-Samuel 1996; Birley 1995). However, in the absence

of a statutory requirement for HIA to be conducted in specified circumstances,

its development has been patchy and fragmented. This is further limited

by the division of the UK into four main territories (England, Wales,

Scotland and Northern Ireland). In each part of the UK, HIA has developed

in slightly different ways, although people engaged in HIA work exchange

information and experiences through relevant academic and policy networks

common to the whole of the UK.

Figure 3: Comments on HIA by

Tessa Jowell MP, [former] Minister of State for Public Health (England,

UK)

- There is a need to develop guidance

to help other [non-health] government departments carry out HIA

to ensure consistency; that the methodology is simple and non-bureaucratic

as possible, yet at the same time the information that is needed

is properly collected (1998).

- Public health has been weakened by

the lack of evidence that supports judgements and decisions about

policies in so many areas. HIAs can underpin and give integrity

to decisions where that has been lacking in the past, so can provide

a very important tool in building the evidence base [for public

health] (1998).

In 1997, the current Labour Government was elected for its first term

in office and was keen to ‘promote the use of HIA as one aspect of

its agenda to modernise and ‘join-up’ the policy making process in

order to tackle complex issues such as poverty, social exclusion and

public health’ (DoH 1999). An early example of HIA guidance in this

new policy environment came with publication of the Merseyside Guidelines

on HIA (Scott-Samuel et al, 1998).

However, that Government’s early pronouncements on HIA

(see Figure 3) (see also DoH Press Office 1998) may have contributed

to present tensions among HIA experts in the UK between those for

whom the ‘process of HIA’ (including public participation) is of primary

importance and those who argue (in the context of an evidence-based

culture) that the methods used should be scientifically rigorous.

3.1.1 Factors affecting the use of HIA in the UK

Table 1 shows these factors that were identified by the Welsh Assembly

Government as affecting the use of HIA. However, reading of other

UK literature shows that these factors are generalisable to England

and Scotland.

TABLE 1: Factors affecting the use of HIA and intersectoral working

in Wales (adapted from: Breeze C and Hall R. 2002)

|

POSITIVE/ENABLERS

|

NEGATIVE/BARRIERS

|

| a. |

Recognition of social and economic determinants of health. |

Gaps in the evidence base of the interrelationships between policy

areas. |

| b. |

Evidence in the links between health and policy areas, and easy access

to it. |

Misconceptions of ‘HEALTH’. |

| c. |

Examples of how HIA has been applied and evidence of how it has helped/benefits. |

Lack of awareness and understanding of HIA. |

| d. |

Strategic use of research funding programmes to expand the evidence

base. |

Narrow or ‘traditional’ views in some policy areas. |

| e. |

Major change that leads to a ‘shake up’ of government organisations

and practices. |

Lack of, or outdated, guidance for policy making. |

| f. |

Political commitment to an integrated approach and commitment to follow

it through. |

Business overload resulting in policymakers concentrating on their

own policy field. |

| g. |

Catalysts, including crosscutting themes as facilitators and drivers

for horizontal action by policy makers. |

Tight timescales of some policy developments. |

| h. |

Systems and processes that facilitate working across policy areas in

the early stages of policy development and implementation. |

Language and terminology – ‘jargon’ – in different policy areas/sectors. |

| i. |

Organisational structure and size E. g. Assembly is one organisation

as opposed to being a series of separate Ministerial departments. |

HIA developed as a ‘separate’ theme without thoughts to it becoming

part of wider developments in policymaking. |

| j. |

Improvements in organisational culture, dynamics and working practices. |

Policy and/or organisational ‘silos’ reinforce vertical structures

and hinder horizontal working. |

| k. |

Health featured as high level strategic objective. |

Organisations that are static in terms of changing their culture and

practices. |

| l. |

Capacity/resources for HIA. |

Process failures or lack of processes for screening of policies and

programmes for their relevance to health. |

| m. |

|

Lack of capacity/resources to undertake assessment within the necessary

timescales. |

| n. |

|

Multitude of impact assessment required increases workloads and resistance

to impact assessment. |

The original table produced by Breeze and Hall appeared to list

factors randomly. In consequence, any later attempt to compare and

contrast Welsh and Hungarian factors needs to start by looking for

categories or groupings of factors.

Drawing, in part, on the capacity building framework

for public health developed, tested and applied in New South Wales

(Hawe et al 2000, NSW 2000) and relationship of evidence to policy/practice

(Nutbeam 2001), the following categories can be identified among the

factors listed by Breeze and Hall. These are from the Table 1:

- Evidence (a-d enablers and a-c barriers)

- Political/policy (e-h enablers and d-i barriers)

- Institutional (i-k enablers and j-l barriers)

- Resources (l enabler and m-n barriers).

In reality, these different categories are interdependent. For example,

new evidence may inform policy decisions and subsequent allocation

of resources. Or, a policy decision may determine priorities for research

funding and hence the type of evidence that is then available to policy

makers. In this analysis, policy and political factors appear to be

the most significant block of barriers affecting the use of HIA in

Wales.

3.1. 2 Lessons from the UK experience

A number of preliminary lessons can be drawn from experience in the

UK. These include:

- Examples of areas addressed by HIA include – transport policy

[Scotland], urban regeneration [Scotland], bio-diversity [London,

England], air quality [London, England], an extra runway for Manchester

Airport [England], the EU funded Objective 1 programme [Wales].

- Increasing recognition of the need to do HIA at policy level,

because of the more wider ranging effects, and wider resource

implication of policy compared to programmes and projects.

- The tendency for ‘health’ to be narrowly interpreted by non-health

sector policy-makers, professionals and the general public. Each

policy area is fed by its own jargon and technical terms. These

can act as barriers to intersectoral working (Wales- Breeze and

Hall 2002).

- The importance of seeing HIA in its wider context i.e. the

development and implementation of Government policy. The ultimate

goal is to help people to improve their health and reduce health

inequalities and to use HIA successfully to achieve this (Wales

- Breeze and Hall 2002).

- The importance of building on capacities that already exist

in a country. In Scotland, people doing HIA case studies benefited

from traditions and available infrastructure supporting inter-agency

working and community participation (Scotland - SNAP 2000).

- Longer-term experience in environmental and social impact

assessments suggest that meaningful approaches to and methods

for HIA will emphasise:

- equitable outcomes

- explicitly targeting disadvantaged groups

- enabling the fullest possible participation by those

groups or communities most likely to be affected by any specific

policy, programme or project

- using qualitative as well as quantitative methods

(England - Scott-Samuel 1996).

- That the HIA process can become unnecessarily long if people

are not able to commit full time to conducting an HIA, writing

it up and supporting its use in the relevant policy processes.

- The lack of a statutory requirement for HIA to be carried out

means that it risks not entering the mainstream of non-health

sector institutional and policy processes. It is important to

mainstream the impact assessment concept in processes, systems

and organisational culture. HIA can’t be viewed in isolation.

- Modernisation agendas for public administration and policy

making should underpin HIA by

- being committed to open and inclusive policy-making

- legitimising collaboration across policy areas on cross-cutting

policy themes such as public health and sustainable development

(Wales- Breeze and Hall 2002).

3.2 HIA in the Netherlands

Development of HIA in the Netherlands has been more coherent and systematic,

particularly in the assessment of national government policy.

The history of the development of HIA in the Netherlands

has been well documented (Put et al 2001). Based on expert consultations

during 1993-4, the Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport informed

the Netherlands Parliament during 1995-6 about the main points of

her policy programme. This included developing a methodology for screening

policy proposals made by other Ministries and identifying those that

might impact on public health. The methodology would also support

more in-depth assessment of policy proposals meeting certain threshold

criteria with a view to exerting influence during the official preparatory

process. (Letters 24/126, No.3 and No 14, Public Health Policy 1995-98).

In 1996, the Intersectoral Policy Office was set up

in the Netherlands School of Public Health (NSPH) in order to

coordinate development of the necessary methodology and a sum of 230,000

euro was allocated to implement a plan of action to develop (see Figure

4)

Figure 4: Main objectives of

the Dutch Plan of Action to develop HIA in 1995

- Make an inventory of existing methods

and tools for impact assessment in the Netherlands, as well as

foreign experience.

- Work out methods for estimating the

size and significance of impacts on health of policy proposals.

- Develop procedures for HIA.

- Assess the performance of HIA in practice.

- Investigate the possibilities for

institutionalising HIA.

(Source: Put et al 2001)

Since then, the total annual budget for the IPO has

increased from 230,000 to 340,000 euros, while the sum allocated for

commissioning specific HIA studies has increased from 65,000 to 95,000

euros. The IPO is financed by the Health Ministry but has independent

control over its budget.

3.2.1 HIAs produced or coordinated by the NSPH/IPO

Table 2 summarises the range of policy areas covered under the Dutch

programme described previously.

Table 2: HIAs coordinated or produced by the NSPH

| Year |

Topic |

Subject Screening (S) or Assessment (A) |

| 1996 |

Energy tax regulation (Ecotax)

High-speed railway |

S

S

|

| 1997 |

Tobacco policy (2 reports)

Alcohol and Catering Act

Reduction of the dental care package |

S

S

A

|

| 1998 |

National Budget 1997/Annual Survey of Care

Tobacco policy

Election programmes of political parties

ICES (Operation Interdepartmental Commission for Economic Structural

Reinforcement – 2 reports) |

S

A

S

S

|

| 1999 |

Housing Forecast 2030

Identification of policy areas influencing determinants of 5 major

health problems

Occupational Health & Safety Act

24-hours economy

Coalition Agreement

Employment Policy proposals and health effect screening

National Budget 1999

Regional development policy |

S

A

S

S

S

S

S

S

|

| 2000 |

National Budget 2000 |

S

|

| 2001 |

Housing Policy

National Budget 2001 |

A

S

|

3.2.2 Lessons from the Dutch experience

A number of early learning points can be drawn from review of Dutch

material to date:

- That systematic use of HIA in the development of national

policies is possible and practical.

- The importance of high level political support for HIA,

with transparency between Ministries and Parliament about the

findings and implications of HIA studies.

- The value of starting carefully and building up to more

extensive HIAs.

- The importance of providing adequate funding to underpin

the development of HIA and an annual commissioned HIA programme.

- The importance of developing an extensive network of

experts capable of taking on the conduct of HIA studies.

- However, more evidence is needed on what HIA can add

to policy-making and this can only come from its application and

then from learning from and sharing such experiences.

4. SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS IN HUNGARY

Drawing on and sometimes mirroring experiences elsewhere in Europe

(see sections 2 and 3 above), this section presents a situational

analysis for Hungary. This analysis is based on interviews with key

stakeholders, review of documentation and participation in the policy

process, particularly relating to attempts to adopt a broader understanding

of public health in policy and institutional circles (see 1.2 above).

4.1 Policy context in Hungary (1999-2002)

In December 1999, as part of a round of international events designed

to share experience and innovation on HIA, Hungary hosted a meeting

on HIA. At that time there appeared to be little interest in the Ministry

of Health in the value of HIA and scepticism about its relevance in

the context of Hungarian policy making. By contrast, the Environment

Ministry was developing capacity in the commissioning and use of environmental

impact assessment.

More recently, in May 2002, the newly elected Socialist/Free

Democrat coalition Government took office following a general election.

Public announcements by senior Government figures seemed to commit

the Government to designing and delivering health-driven policy in

all sectors of public administration. This mirrors the range of competency

in health matters set out in the Treaty of Amsterdam of the European

Union. Not without coincidence, Hungary is on track for accession

to the EU in May 2004.

This new approach to healthy public policy will, for

this Government, be underpinned by intersectoral action on health

and continuing reform of public administration in Hungary. Together,

they appear to provide a supportive environment for the introduction

and implementation of HIA.

More concretely:

- a new Public Health Division was established at the Ministry

of Health, Social and Family Affairs in September 2002 with

interest in championing health development

- provision for a regional health development function alongside

Regional Development Committees was included in the National

Development Plan for Hungary submitted to the EU

- the Hungarian Parliament will debate a new National Public

Health Programme sometime in March 2003

- subsequently, further strategic and institutional development

in the areas of health development and Public Health are planned

during 2003-2005.

One of the options under consideration is that HIA can be institutionalised

in the governmental sector through a new background Health Policy

Institute that could be established in relation to the MoHSFA.

4.2 Factors affecting the use of HIA in Hungary

The factors discussed in this section are drawn from interviews conducted

with key stakeholders and analysis of documents in order to contribute

to a situational analysis of HIA in Hungary. Table 3 summarises these

factors.

As with Table 1, the factors presented in Table 3 can

be grouped into four main categories for comparative purposes:

- Evidence (a-c barriers)

- Political/policy (a-d enablers and d-i barriers)

- Institutional (e enablers and j-m barriers)

- Resources (f-i enabler and n-q barriers).

A quick look at table three shows a considerable number of barriers

and far fewer ‘opportunities’ than identified in the UK context. However,

not all stakeholders had an adequate overview of the developments

listed in 4.1 above most of which may facilitate the introduction

of HIA in Hungary.

TABLE 3: Factors affecting the use of HIA in Hungary

|

POSITIVE/ENABLERS

|

NEGATIVE/BARRIERS

|

| a. |

International policy priority for HIA. |

Lack of awareness and understanding of Health and HIA. |

| b. |

New National Public Health Programme. |

Public Health is a too complex issue. |

| c. |

Political commitment to the use of HIA. |

An insufficient evidence base in HIA. |

| d. |

The need for regionalisation and decentralisation together with the

opportunity to the use of HIA in regional decision making. |

The lack of political commitment to follow through policy announcements. |

| e. |

Institutional development in the Ministry of Health and a new

National Institute for Health Development. |

Unwillingness to really address required system level and organisational

level changes, together with immature political culture. |

| f. |

EU accession in terms of potential collaboration with foreign

partners in HIA project. |

Lack of policy process and strategic thinking and short term interest

conflict with long term development. |

| g. |

Possible interest in the Ministry of Finance to consider use of HIA

to identify and assess health ‘cost’ of policy proposals from spending

Ministries. |

Public Health is not an issue in politics. |

| h. |

Stakeholders interested in HIA. |

Lack of political and professional consensus in Public Health Policy. |

| i. |

Other approaches to evaluate health impact. |

There is discrepancy between policy and research. |

| j. |

|

Key stakeholders don’t share information and don’t work in teams. |

| k. |

|

Immature programme management, unclear responsibilities, weak accountability,

poor performance. |

| l. |

|

There is no partnership between health and non-health sectors for HIA,

and weak intersectoral working for health. |

| m. |

|

Conflicting interests in HIA. |

| n. |

|

Lack of capacity (institutional. Human resources, working examples,

guidance or training materials) for HIA. |

| o. |

|

Weak social capital (trust, confidence) for participation in HIA project. |

| p. |

|

Lack of legal framework for HIA. |

| q. |

|

There is too little time available for HIA before decision making. |

4.2.1 Opportunities in Hungary

a. There is increasing recognition by governments of the importance

of HIA and the needs for international collaboration in order to share

experience, best practice and learn from each other. This is reinforced

by the Article 152 of The Amsterdam Treaty for Member States of the

European Community and the World Health Organization’s Health 21 policy

framework for countries in its European region (Pan-European HIA survey,

2002).

b. The government accepted a new National Public Health

Programme in December 2002 for the next decade. One of the priorities

in the Program is capacity building for health development including

capacity for HIA.

c. The newly elected Socialist/Free Democrat coalition

Government says that it is interested in and committed to the use

of health impact assessment and it is a priority to develop capacity

for HIA.

d. The necessity of decentralisation and regionalisation

is intended to re-allocate power more appropriately between national,

regional and local levels. That should happen in Hungary in the context

of EU accession. The EU will allocate resources for regional development

and Hungary needs to prepare it’s infrastructure for this. That will

open up the regional level of decision making, governance and program

delivery, This will provide a new arena for the application of HIA

in decision making processes.

e. The national government established a new Division

for Public Health in the Ministry of Health, Social and Family Affairs,

and recently accepted a new National Public Health Programme. The

Program will have a new background institution for policy analysis-advice,

program management and health development. Capacity building for Health

Impact Assessment and co-ordination of the related tasks is intended

to become a new function of this Institute.

f. EU accession opens up a new perspective for Hungary

in terms of development of the use for HIA. For example, through collaboration

opportunities with EU partners. Participation as a third party in

the SANCO project would provide valuable experience, knowledge and

importantly, potential leverage to develop the required capacity in

Hungary.

g. Previous discussion involving a Ministry of Finance

colleague dealing with social expenditure, showed interest in getting

a better understanding of HIA as a step to considering its possible

use in identifying and assessing policy proposals from spending Ministries

for potential ‘health costs’ and/or ‘added health value’.

h. Interviewed stakeholders and government have positive

attitude to the use of HIA and they are interested to develop capacity

for it.

i. At present, the baseline situation in Hungary

is a lack of obvious capacity for Policy HIA both within the health

sector and outside of the health sector. Some related infrastructure

and resources exist for example in the:

- Local Health Planning Project of the Hungarian Healthy

City and Soros Foundation

- Ministry of Environment and other bodies for Environmental

Health Impact Assessment

- Ministry of Youth and Sport for the impact of the new ‘drug’

law on the users

- Central European University in terms of integrating Health

into EIA in Central and Eastern Europe (Cherp, 2002). However,

Hungary wasn’t included in the latter activity.

4.2.2 Barriers in Hungary

a. There is a lack of understanding or, at best, a passive awareness

that:

- improved health and quality of life comes mainly from economic

and social developments (including good education) and not

from the health sector and there is a need to assess that

development by HIA

- the technical resources (infrastructure and people skills)

for health impact assessment must be developed

- efforts to improve health must involve working in partnership

with other sectors and with local people.

b. Classical public health with its focus primarily on communicable

diseases, secondary prevention and hygiene protection remains important

in Hungary. However, an efficient public health effort must focus

on helping to reduce inequalities especially as Hungary cannot avoid

the impact of modernisation and globalisation. This requires holistic

thinking to develop well-rounded and appropriate solutions.

c. The evidence base to support HIA is lacking or insufficient

and its application is missing or not appropriate. There is a perception

that Public Health research is very weak in Hungary and there is a

serious lack of resources. The evidence base, concepts, models and

examples that would help Hungary modernise its approach to Public

Health is mostly in English and available only for those who can read

it.

d. There is often a lack of follow-through from political

commitment to implementation in Hungary. There may be several reasons

for this. First, politicians gain profile simply from announcing policy

initiatives and do not seem to be so interested in what happens afterwards.

Second, there can be a lack of obvious mechanisms by which policy

can be translated into action.

e. After the political, economical and social changes

Hungary is still in the process of transformation. Based on my interviews

with key stakeholders and research experiences there is a very real

unwillingness to address the need for system and organisational level

changes. This is made worse by a still developing pluralistic political

culture, disempowered institutions and civic society and, at a basic

level, concerns about job security in a period of significant change.

At the same time EU accession and developmental needs will require

new ways of working, new knowledge, skills to fulfil expectations.

f. Since 1989 Hungary had at least 6 National Public

Health Programme and basically no implementation so far. There was

no clear strategic view about public health and no proper planning

for implementation or institutional development. Within one national

governmental cycle we had several ministers, new organisational structures

and functions, new management or no management. At the same time short

term interests of people within a rigid bureaucracy are barriers to

long term development.

g. Public Health comes up the political agenda during

the last election campaign but seems to fade away after the election,

being overtaken by more pressing reactive/emergency concerns.

h. Mirroring other factors mentioned above, stakeholders

don’t share information, and in only a few areas (such as drug prevention)

is there obvious partnership working.

i. As happens elsewhere, policy and research have different

speeds and natures. The lack of commitment to evidence-based policy

and practice does not provide supportive conditions for using research

in decision-making at policy and practice levels. Policy sometimes

seems to be designed as much as a means of spending the Government’s

short-term budget as it is of addressing basic challenges facing the

Government (wealth creation, social inclusion, public health, democracy).

j. Related to point ‘e’, the working culture within

the health sector and especially within key organisations in the public

health field is based on an out of date command and control approach

combined with a strong sectoral, rather than intersectoral orientation.

It appears that the past 10 years of transition have reinforced this

culture causing organisations and individuals to be afraid and suspicious

to share information and to want to work in teams.

k. In the public health field program management skills

are under-developed, responsibilities are unclear, the accountability

of programmes is weak and performance is poor or not well measured.

One of my interviewee told me that “people are not following roles

and regulation in the Parliament either” (for example the enforcement

of the No Smoking in Public Places Law).

l. Hungary has experience of intersectoral working (World

Bank Health Programme projects, Healthy Cities and Regions for Health

Networks) but have not been able to successfully institutionalise

this. Working in partnership with each other requires new way of thinking

and application of new approaches, methods, tools, etc. Health Impact

Assessment potentially provides a concrete and practical way of increasing

commitment by health and other non-health sectors for better health

and quality of life for people.

m. There are different stakeholders and institutions

in different policy proposals and programme and they can have conflicting

interests to carry out HIA.

n. To date, Hungary has not identified clear institutional

responsibility for coordinating the development of expertise and knowledge

in HIA including the production or/or translation of specific guidance

or training documentation on health impact assessment.

o. Social capital (trust, confidence, knowledge) between

agencies and individuals is weak in Hungary. A paradox of the Socialist

period is that it undermined social capital and replaced it with a

system of state dependency and patronage. Hungary is still passing

though its transformation and it may still be too early after the

system change for significant levels of social capital to have developed

again. As HIA and similar participatory techniques become more widely

used and familiar it may help lead to develop strong confidence and

capabilities in represent broader stakeholder views in the development

of policy and programmes.

p. Hungary has a regulation for social, economical and

environmental impact assessment, but no law for HIA.

q. Sometimes there is too short time for any impact

assessment before decision making. This reality is, in part, responsible

for scepticism for using methods like HIA that ‘delay’ decision-making.

What does not seem to be appreciated is that HIA and similar policy-planning

tools can help improve the quality of policy decision making and,

in consequence, improve the effectiveness and relevance of measures

to implement policies.

5. COMPARISON OF FACTORS AFFECTING THE USE OF HIA

IN HUNGARY AND THE EU

In the UK there appears to be a critical mass of factors at a policy

level that will help promote wider adoption of HIA and related methods

at Institutional and other levels. By contrast this critical mass

has not yet been achieved in Hungary. In part this may be because

of a lack of a broader modernisation agenda for Government/public

administration of the kind seen in the UK and elsewhere. Hungary has

a lot of developmental needs to deal with all the barriers in relation

to the application of HIA methodology. Capacity building means working

on several levels: political, strategic, (inter) institutional and

training.

Learning from the Scottish experience shows that several

actions need to be taken in order to have a real chance for developing

health impact assessment and making healthy public policy:

- There need to be a clear understanding of the responsibilities

and the functions of the institutes and organisational structures

in the field of public health and health promotion.

- A cross departmental audit is needed among the Ministries in

order to ‘map’ how much health is in the centre of the policy

making process.

- A system of control (a kind of checklist) has to be developed

to screen policies for potential health impact and then to help

identify the positive and negative effects of the important health

relevant policies.

- If it is necessary, a detailed HIA should be commissioned.

- Case studies have to be shown concerning how previous assessments

managed to prevent damage or harm or produced benefits. Criteria

have to be formed and prioritised which help to select policies

which should be subjected to HIA later on. This method was used

for example in The Netherlands. Responsibility for case finding

would lie within the health sector.

- Every kind of initiative, programme which can have an impact

on the quality of the life of the people has to use a monitoring

system which places health in the centre, and where it is needed

it has to have mechanisms by which we can intervene.

- External audit is needed whether health is considered in policy

making at local, regional and national level (Adapted from SNAP,

2000).

Evidence

The Welsh study found 4 factors supportive of the use of HIA while

none were mentioned by Hungarian stakeholders. In Wales and the UK

generally, there has been for some years a political and policy supported

drive for evidence-based decision making. In turn, this has helped

to generate funding for applied research that can be used to support

decision making. This situation is not the case in Hungary at present.

A problem is that much work on HIA is published and reported in English

but English language (and other foreign language) skills are not widespread

in public administration. Without either improving English language

skills (as is being done in the Military following joining NATO) or

making this English evidence base available through significant investment

in translation, Hungary can’t take advantage of this investment and

learning from abroad.

Political/Policy

The political/policy factors are the most significant category of

barriers in both countries. However, the nature of negative factors

is different in Hungary than in Wales. In Hungary the main problems

are the lack of a transparent policy process, political commitment

to follow through policy announcements, limited means for exploring

and making consensus among sectors and stakeholders around shared

policy priorities, unwillingness to address system and organisational

level changes, discrepancy between policy and research and no priority

for public health. In contrast Wales has the following barriers: narrow

views in some policy areas, lack of policy guidance, business overload,

tight timescales, terminology jargon and HIA is not a part of decision

making. Positively, in both countries there is a political commitment

to the use of HIA and major changes in the policy environment are

supportive factors as well. There are other differences between the

two countries. In Hungary international and national level policy

priorities are positive contributors, while in Wales HIA, as a crosscutting

catalyst for horizontal action, and systems and processes that facilitate

working across policy areas are enablers to the use of HIA.

Institutional

Institutional factors as barriers are almost equally important in

Hungary and Wales as well, but as enablers it is more significant

in Wales. Critically, the Welsh Assembly Government supports the use

of HIA in decision making, among policy implementation agencies health

is a high level strategic objective and different improvements at

organisational level are being made. In Hungary, the Ministry of Health,

Social and Family Affairs established a new division for Public Health

and they have an intention to re-establish a new National Institute

for Health Promotion in Hungary. These developments can be supportive

to the use of HIA at national policy level.

In both countries, important barriers include: weak

horizontal working for health and organisational unwillingness to

change cultural and working practices. In Wales one additional problem

is the apparent failure of processes to screen policies for their

relevance to health. In Hungary immature program management, unclear

responsibilities, weak accountability, poorly monitored performance

and conflicting interest in HIA are all barriers to the use of HIA.

Resources

This category is more significant determinant both as enablers and

barriers in Hungary than in Wales. The Hungarian study found 4 – 4

factors as opportunities and barriers to the use of HIA. Among the

opportunities are EU accession, interest among stakeholders and Ministry

of Finance interest in HIA and other approaches to evaluate policy

proposals submitted by spending Ministries. Among the barriers there

are the lack of capacities and legal framework for HIA, weak participation

and too little time availability before decision making. In Wales

capacity and resources for HIA are enablers to the use of HIA, while

too little time before decision making and increases workloads are

barriers to the use of HIA.

6. CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

The attention paid in this paper to HIA does not minimise appreciation

that Government and public administration in Hungary is confronted

by many significant challenges, especially related to EU Accession.

In that sense, attention to HIA might seem a luxury. However, the

attention given to HIA is important because it helps to illustrate

how these broader challenges are/are not being met.

According to the findings of this research the following

areas should be addressed in developing action at political, institutional

and professional levels

- Hungary needs to deal with those political/policy barriers

that are in the way of developing the use of HIA at national governmental

level. At the same time Hungary can use the support from the international

community and from its own development opportunities as well.

- The Minister for Health, Social and Family Affairs should have

responsibility for reporting to Parliament, at least annually,

on Screening activity and HIAs conducted and-or commissioned and

what subsequent action was taken by relevant Ministries and organisations.

This would also ensure that other Ministries have to account for

corrective actions taken or not taken in response to HIAs

- Hungary needs to address problems located in institutional

cultures, structures and relationships, developing a new attitude

and practice for organisational culture that is supportive of

evidence-based decision making, intersectoral and team working

and involving target population groups

- Key stakeholders, especially public health professionals and

researchers need to develop and promote the necessary evidence

base to support the use of HIA

- In terms of resources Hungary needs to identify and exploit

the opportunities that are available and with realistic budgets,

start to develop capacity to carry out HIA.

Relatedly, experience from elsewhere shows important directions for

the development of HIA in Hungary. For example,

- Carrying out HIA should be an essential part of government

planning and decision making in order to place health in the centre

of the decision making process.

- When facing potential health risk detailed impact assessment

is needed in the interest of eliminating the risk or achieving

a better health gain.

- Carrying out HIA is reasonable and practical, with findings

from a HIA it is really possible to make changes in the decision

making process.

- The HIA should be jointly owned by the health and other sectors.

Determining that a HIA is necessary and initiating it should be

a cooperative decision between the relevant ministries. Negotiating

and implementing the recommended modifications is the responsibility

of the relevant decision makers and government offices.

- HIA can be an integrated part of other impact assessments but

also can be carried out independently. The selection of the necessary

methods and tools depends on the specific task (Adapted from SNAP,

2000).

More specific policy recommendations will be addressed in a parallel

policy briefing paper. The main recommendations are given below.

6.1 Establishing a legal framework for HIA in Hungary

If it is possible, existing capacities should be used and built on

it. It is important to ‘map’ recent impact assessments in the country

taking into considerations their legal regulation. These can be used

as models for forming the regulation for the implementation of HIA.

The Parliament should adopt a resolution as first step

which is essential and necessary for the legitimacy of HIA. For example

there is no document like this in the UK. Only the Environmental Impact

Assessments are regulated by the law. This was created within the

frame of EU regulation. This is why it would be important for Hungary

to take part in a potential EC pilot project (meeting on the topic:

on the Hague conference, 17-23 2002). This could help the formation

of this resolution which would regulate the HIA at the formulation

of those policies which might influence the health status of the people.

6.2 Building capacity

The Hungarian Government should develop mechanisms to consider health

in national policy making, and to support this at all levels. The

assessment of health impacts of policies at national level should

be a priority since the achieved effects are more fundamental and

resource efficient than confining assessment at local or program level.

The Ministry of Health, Social and Family Affairs together

with other sectors (e.g. Ministry of Finance, Prime Minister’s Office)

should support the implementation and use of HIA in Hungary as the

integral part of strategic decision making both at national and at

local government offices and other organizations.

After the necessary preparations a National Advisory

Group should be formed under the New National Public Health Program,

which would be responsible for supervising a Unit dealing with supporting

the implementation and use of HIA in Hungary.

6.3 Institutional development

An independent Research and Development or Health and Public Policy

Unit has to be formed, which is responsible for developing a plan

for implementation and support of technical protocols of HIA in Hungary.

There are several alternatives for positioning such a Unit.

First, the Unit could work within a frame of a civil

organization in order to have opportunities to get resources not only

from the government. This civil organisation should use accessible

and existing experiences and results of both national and international

research projects (e.g. M. Ohr, OSI/IFP research, capacities of the

CEU, Ministry of Environment, others).

Second, funding could be provided for a Unit working

within a background institute of the Ministry of Health, Social and

Family Affairs. This Unit advises on those policies which have to

be examined concerning their potential impact on health, supports

screening within the relevant Ministry and where necessary conducts

or commissions full HIAs. The results are communicated to the Ministry

that is responsible for acting upon the recommendations.

Third, other alternatives are (i) this Unit could be

established as a background Institute to the Ministry of Finance,

recognising that Ministry’s role in determining the shape of the Government’

policy programme (ii) placing the Unit within the Prime Minister’s

Office, as part of a broader drive to modernise Government and public

administration.

7. REFERENCES

Az Egészség Évtizedének Johan Béla

Nemzeti Programja, Budapest, 2002, Miniszterelnöki Hivatal

Birley MH (1996) The health impact assessment of development

projects. Journal of Public Health Medicine, 248-249.

Blane D., Brunner EJ. and Wilkinson R. (1996) The evolution

of public health policy: an anglocentric view of the last fifty years.

In Blane D., Brunner EJ. and Wilkinson R. (eds.) Health and Social

Organisation: towards a health policy for the 21st century. London:

Routledge.

Breeze C (2003, in press) Health Impact Assessment and

government policymaking in European countries: a position report,

draft report before publication

Breeze C., and Hall R. (2002) Health Impact Assessment

in Government policymaking: Developments in Wales, WHO Policy Learning

Curve Series # 5. Welsh Assembly Government and WHO European Centre

for Health Policy: Brussels.

Cabinet Office (2000) Wiring It Up: Whitehall’s Management

of Cross-Cutting Policies and Services. A Performance and Innovation

Unit Report, London: Cabinet Office.

Cherp, Aleg 2002 Integrating Health into EIA in CEE.

22nd Annual Conference of the International Association for Impact

Assessment, 15-21 June 2002, the Hague, Netherlands.

Department of Health (1999) Saving Lives: Our Healthier

Nation. The Stationery Office: London

Department of Health Press Office (1998) Health Impact

Assessments will help measure action in tackling inequalities.

(www.official-documents.co.uk/document/cm43/4386/4386-04.htm1)

Department of Intersectoral Policy, Netherlands School

of Public Health (2000) Plan of Action 2000-2001, NSPH: Utrecht.

European Centre for Health Policy, Health Impact Assessment:

main concepts and suggested approach, Gothenburg consensus paper,

December 1999.

European Centre for Health Policy, Policy Learning Curve

Series, Number 4, Experience with HIA at national policy level in

the Netherlands. A case study, September, 2001.

European Centre for Health Policy, Health Impact Assessment.

Discussion papers, Number 1. Strategies for institutionalizing HIA.

Reiner Banken, September, 2001.

European Union Article 152 (1997) the Amsterdam Treaty.

Brussels: European Commission

Gillies P. (1998) Social capital and its contribution

to public health. In: E. Ziglio, D. Harrison (eds) Social Determinants

of Health: Implications for the Health Professions. Genoa: Italian

National Academy of Medicine, pages 46-50.

Hawe P, King L, Noort M, Jordens C, Lioyd B (2000) Indicators

to help with capacity building in health promotion. Sydney, Australia:

New South Wales Health Department.

Lavis J and Sullivan T (1999) Governing Health. In Drache

D. and Sullivan T. (eds.) Health Reform: Public Success and Private

Failure. London: Routledge.

Leung, S.F. and Wong, C.T. (2002) Health Status and

Labor Supply: Interrelationship and determinants. Hong Kong

University of Science and Technology, 28 May

Levin LS. and Ziglio E. (1996) Health promotion as an

investment strategy: considerations in theory and practice. Health

Promotion International 11(1): 33-40.

Marmot M. and Wilkinson RG. (eds.) (1999) Social Determinants

of Health, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

NSW Health (2000), Capacity Building Framework. Sydney,

Australia: New South Wales Health Department.

Nutbeam D (2001) Evidence-based public policy for health:

matching research and policy need. Promotion and Education 2, supplement:

15-19

Plan of Action 2000-2001, Department of Intersectoral

Policy, Netherlands School of Public Health, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Put GV, den Broeder L, Penris M and Roscam Abbing, EW

(2001) Experience with HIA at National Policy level in the Netherlands:

a case study. WHO Policy Learning Curve Series # 4. WHO European Centre

for Health Policy: Brussels

Scott-Samuel A., (1996) Health Impact Assessment, An

idea whose time has come, BMJ 313, Equity in Health Research and Development

Unit, Department of Public Health, University of Liverpool, L69 3BX

Scott-Samuel A, Birley M and Arden K (1998) The Merseyside

Guidelines for Health Impact Assessment. Liverpool: Merseyside HIA

Steering Group.

Scottish Needs Assessment Programme, (SNAP, 2000) Health

Impact Assessment: Piloting the Process in Scotland, Office for Public

Health in Scotland: Glasgow.

Watson J., Butcher P., Mogyorósy Zs., and Ohr

M. (2001) The contribution of public health to national development.

Findings from an introductory workshop with Hungarian stakeholders.

Workshop report.

Wilkinson R. (1996) Unhealthy Societies: The Affliction

of Inequality. London: Routledge.

World Health Organization (1999) Health 21: The health

for all policy framework for the WHO European Region. European Health

for All Series No. 6. Copenhagen: World Health Organization

Ziglio E et al (2000) Technical Report 2: Investment

for health. For Fifth Global Conference on Health Promotion, Mexico,

5-9 June.

Back to home page